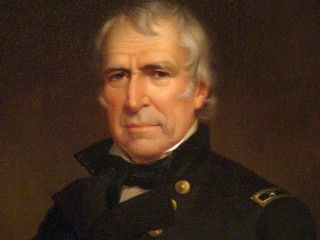

Zachary Taylor biography

Date of birth : 1784-11-24

Date of death : 1850-07-09

Birthplace : Orange County, Virginia, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-09-21

Credited as : Politician, former U.S. President,

8 votes so far

If I occupy the White House, I must be untrammelled and unpledged, so as to be president of the nation and not of a party." --Zachary Taylor

American leader, whose emergence from a long military career as a hero of the Mexican War catapulted him from relative obscurity outside the army to the presidency of the United States.

* 1808 Commissioned a first lieutenant in U.S. Army

* 1812 Indian attack on Fort Harrison repulsed

* 1815 Resigned commission as captain

* 1816 Recommissioned as major

* 1832 Black Hawk War

* 1837 Arrived in Florida to Seminole Indian troubles

* 1846 Commanded battles of Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey in Mexican-American War

* 1847 Commanded battle of Buena Vista

* 1848 Elected president on Whig Ticket

* 1849 Inaugurated; sectional conflict intensified

* 1850 Died on July 9, before settlement of compromise

Early years

Born on November 24, 1784, to Richard and Sara Dabney Strother Taylor; died on July 9, 1850, of apparent food poisoning; married: Margaret Mackall Smith, June 21, 1810; children: four daughters and one son. Predecessor: James K. Polk. Successor: Millard Fillmore.

Little is known about the Kentucky childhood and adolescence of Zachary Taylor. Born on November 24, 1784, this future U.S. president was the third of Sara and Richard Taylor's nine children. His father had served as a Virginia militia officer in the Revolutionary War and received a war bonus for his services in 1783, a grant of 6,000 acres in the western lands of Virginia. In Kentucky, which would gain its independence from Virginia in 1792, the war veteran chose land for a plantation six miles outside the young settlement of Louisville. Thus, in the summer after Sara Taylor gave birth to Zachary in Virginia, Richard Taylor moved his family to Kentucky.

The Taylors became a family of some distinction in Louisville; Richard occupied himself with running his small plantation, speculating in land, and serving the public in such capacities as fighting off Indian incursions, justice of the peace, collector of the Louisville ports, delegate to the convention to draw up a state constitution, state legislator, and presidential elector.

Although Richard Taylor seems to have graduated from William and Mary and Sara Taylor received instruction from European tutors in her youth, their children appear to have received very little formal education. Zachary, who has never been described as an intellectual, possibly attended two different schools for brief periods. Whereas one president who served not too long after Taylor managed, as an ardent autodidact, (self-taught person) to compensate for his lack of formal education, Zachary Taylor never betrayed a yearning for book learning.

Taylor's Career

That he did receive a thorough education in the management of a plantation cannot be doubted, for he lived at home until the age of 23. The Taylor property was somewhat isolated, so it is safe to assume that from a young age, Zachary learned firsthand the mechanics of farm life. And he grew up with slavery. Richard Taylor owned seven slaves in 1790, 26 in 1800, and 37 in 1810. Zachary Taylor, who joined the ranks of the many slaveholding presidents who preceded him, would acquire a good many more slaves than his father during his lifetime.

In the spring of 1808, the U.S. Congress increased the size of the national army almost threefold in response to a war scare with Great Britain precipitated by the Royal Navy's firing upon the American ship, the Chesapeake, in June 1807; three crewmen were killed and four forcibly removed from the ship. Zachary Taylor was commissioned a first lieutenant in the 7th Infantry in May 1808. The first year of his service was occupied with recruiting men to fill the expanded ranks of the army while the second was spent in New Orleans to fend off a British attack which never materialized. He returned to Louisville in May 1810 and married Margaret Mackall Smith the following month, receiving from his father as a wedding present a 324-acre farm. November of that year brought him promotion to the rank of captain.

Taylor was posted to Indiana Territory in July 1811, where he remained for the duration of the War of 1812 with the exception of an official trip to Maryland (a brief sojourn which prevented him from participation in William Henry Harrison's Tippecanoe campaign) and a brief stint in recruiting in Louisville. When the U.S. declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812, Captain Taylor was stationed at Fort Harrison, Indiana. In September of that year, the fort received, and repulsed, a severe Indian attack at a time when Taylor's forces were seriously undermanned. By all accounts, Taylor behaved courageously, authoritatively, and energetically in response to the crisis and deserves a large measure of the credit for the garrison's survival. Later in the war, Taylor carried out orders to lead retaliatory missions upon Indian settlements, but in general he saw limited action in this conflict. Though he had been promoted to major in the course of the war, with the coming of peace, his rank was reduced once more to that of captain, leading him to resign his commission in June 1815 in order to return to the farming life.

Within a year, however, Taylor was offered reentrance to the army with the rank of major, an offer gladly accepted by a man with an enlarging family, marked by the birth of a third daughter in August 1815. Ordered for a short while to Fort Howard, Wisconsin, the major soon found himself once more engaged in a Louisville-based recruiting effort. The year 1819 brought Taylor promotion to lieutenant colonel and assignment to the 8th Infantry, then engaged in building military roads in Alabama. The following was a less fortunate year for the soldier--two of his daughters died of a fever which their mother only barely survived--but he did receive reassignment to the then-southwestern frontier of the country where he spent the majority of the next eight years.

In 1828, the Taylors received orders to relocate once more to Minnesota, and they spent the next nine years stationed at forts in and around the upper Mississippi area. His most taxing duties involved the struggle to win the Black Hawk War and then to secure ensuing peace by guaranteeing the established rights to land which the U.S. government granted to the losing Indians. In 1835, while stationed at Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, his daughter, Sallie Knox Taylor, met one of Taylor's subordinates, the future Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Because Taylor did not want his daughter subjected to the inherent family dislocations of the military life, the courtship was carried on at an aunt's home. Davis resigned from the army and married Sallie on June 17, 1835, in Louisville, Kentucky, with neither family present. Tragically, both Davis and his bride developed malaria during a summer visit to a sister's plantation in southern Mississippi, and Sallie died on September 15.

Taylor Acquires Military Nickname

Taylor and his regiment were ordered to Florida in 1837 to deal with troubles with the Seminole Indians, where two years previously the government had begun to prod the tribe to resettlement lands in the West. That same year, Taylor commanded the troops of varying quality in the battle of Lake Okeechobee, the bloodiest and most extensive of the seven-year conflict with the Seminoles. The following couple of years were less dramatic but taxing in their own way, as Taylor chafed at the region's irrepressible humidity and at being stationed in what was by then a low-profile command. That he was popular with his men is attested to by the fact that it was in Florida that he acquired the nickname "Old Rough and Ready" for his identification with the enlisted men, his dislike for excessive formality, and his readiness to share their physical hardships.

Relieved upon his own request from Florida duty in spring of 1840, the following year found him stationed once more in the Southwest, commanding a succession of forts along the Red and Arkansas rivers. Although Taylor was a large slaveholder, owning several plantations and 145 slaves by 1848, he did not support efforts to secure the annexation of the Republic of Texas, negotiations that dragged on through 1843-44. During this period, Taylor was ordered to command a corps of observation along the U.S.-Texas frontier until July 4, 1845, when Texas agreed to the terms of annexation. At that time, at the joint request of Texas and the United States, Taylor was ordered to the Texas-Mexican border as a show of strength against an undoubtedly angered Mexican state. In January 1846, this Army of Occupation was ordered to the southern boundary claimed by Texas, a move which violated Mexican territory, by that country's definition of the border. By late March, Taylor's forces reached the Rio Grande, the boundary claimed by Texas, 100 miles south of that claimed by Mexico.

Although the United States and Mexican armies were encamped across the river from each other for nearly a month, it was not until April 24 that the Mexicans launched an offensive. The American forces were heavily outnumbered at the war's outset. In early May, Taylor commanded the U.S. forces at the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma in which his forces were outmanned by a factor of three-to-one and yet in both cases the Americans managed to inflict costly defeats upon their opponents. On May 13, President James K. Polk accompanied the United States' declaration of war with the appointment of General Winfield Scott to overall command in the field. Polk, for various reasons, remained in the national capital until September and therefore Taylor was awarded the brevet rank of major general and given temporary command.

He Becomes Hero in Mexican-American War

Taylor received orders from Washington to attack the Mexican stronghold of Monterrey, to which the enemy forces had retreated. After the U.S. forces stormed the city with great success in September, Taylor accepted the mayor of the city's offer of complete surrender in return for an eight-weeks' armistice, a decision which infuriated Polk when word of the deal reached him. Soon, General Scott arrived in Mexico and assumed priority of resources for his strategic mission. Though Taylor was increasingly pushed to the backwaters of the military theater, he did fight one more major battle, that of Buena Vista, in February 1847. Despite the fact that many of his men had been siphoned off to support General Scott's effort, Taylor and his troops managed courageously to fight back the assault of the Mexican leader Santa Anna. Frustrated with the reduced importance of his command, Taylor requested a six months' leave of absence, which was granted to him in November, and he never returned to the theater. As throughout his career, Taylor's main attributes as a general in the Mexican-American War were his ability to inspire his men to fight and his remarkable personal bravery in battle. He was certainly not an imaginative strategist, but the American public did not view his victories in the war's first ten months with critical eyes; they sought a military hero and conferred the title upon Zachary Taylor.

Taylor was technically in command of forces in Mexico, even while on his extended leave, until he took over command of the Western Division in July 1848. He was mentioned as a potential presidential candidate in the early days of the war. Thurlow Weed, the influential New York Whig editor, pressed the case at an early date as did Taylor's good friend, Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky. Because Whigs were seen as having opposed the war effort at the outset, Taylor, the war hero, was a particularly attractive candidate for the party. Whenever Taylor was asked his opinion on becoming a candidate, he stressed that the presidency was a truly national office. As such, he wanted to be nominated not as a sectional or a special interest candidate, but as a man above petty party rivalries or geographical differences.

Taylor Elected 12th U.S. President

When the national Whig convention met in Philadelphia in June 1848, Zachary Taylor received the presidential nomination on a ticket with New York congressman Millard Fillmore. As Taylor was a slaveholder who supported the maintenance of the institution where it existed, even though he opposed its extension, a combination of Conscience Whigs and other groups dedicated to the end of slavery held a protest convention in August, nominating former president Martin Van Buren on a ticket with Charles Francis Adams as the Free Soil offering for president. The Whig nominee remained on active duty with the army throughout the fall campaign, allowing party members throughout the country to stump in his behalf. The future president Abraham Lincoln traveled across his home state of Illinois for Taylor. On election day, November 7, 1848, Zachary Taylor was elected the 12th president of the United States over Martin Van Buren and the Democratic nominee, Lewis Cass.

The new president had great distaste for the "spoils system" and made his cabinet selections in large part without heed to the demands made of him for patronage. This was unfortunate for two reasons. First, it put him on bad terms with a number of disgruntled fellow party members. Second, the men whom he chose happened to have very limited influence on Capitol Hill, a fact which initially bothered the president very little. Taylor had an idea that domestic policy should be dictated by the legislature, with minimal executive interference. He did apportion to the presidency, however, a greater role in the formulation of foreign policy. He ran his cabinet in a fashion reminiscent of his military background, delegating as far as possible to subordinates whom he trusted to live up to his expectations.

He made little effort to diminish the distance between himself and the capital's career politicians. He arrived in Washington a military hero, but ultimately as an outsider, and his failure to smooth the relations between the executive and legislature certainly did not help and probably exacerbated the sectional conflicts which emerged from the land acquired through war with Mexico. President Taylor's military career bound him by oath to uphold the Constitution; a rupture of the Union was to him unthinkable. While a Southerner and slaveholder, Taylor did not sympathize with the South's defensive posturing and its rumblings of separation in 1849-50.

From the Mexican War, the U.S. acquired the lands of New Mexico, Utah, and California. The South was understandably anxious lest all three be one day admitted as free states and thereby disrupt the fragile sectional balance in the Senate. All contemporary accounts indicate that the belief that the Union was in grave danger was prevalent. Here, when President Taylor could have exercised genuine leadership, he failed to work with Congressional leaders to resolve the sectional crises. Precisely because the president is the primary leader elected on a truly national basis, he is ideally suited to prevail on legislators for unity. Without significant consultations with Congress, Taylor presented his plan for resolution of the conflict in his first annual address, one which had minimal effect. Instead, the debate played itself out entirely within the halls of Congress, with Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun making the impassioned pleas for different interests, a process which resulted in the Compromise of 1850, based on Clay's plan. Zachary Taylor died of suspected food poisoning on July 9, 1850, after a five-day illness, before the compromise was finalized.

It is difficult to pass a definitive judgment upon a presidency which lasted only a year and a half, but there is little indication in Taylor's past that he was an innovative or particularly supple thinker or that he was likely to "change his spots," so to speak. Had he served a full term, it is unlikely that his leadership would have improved with time. He was a man who was disinclined to take chances, to change his mind, or to seek reconciliation with estranged friends.