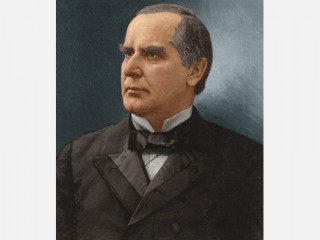

William McKinley biography

Date of birth : 1843-01-29

Date of death : 1901-09-14

Birthplace : Niles, Ohio, U.S.A.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-09-21

Credited as : Politician , former U.S. President,

2 votes so far

McKinley's "kindly nature and lovable traits of character, and his amiable consideration for all about him will long live in the minds and hearts of his countrymen." --Grover Cleveland

Twenty-fifth president of the United States, and the third to be assassinated, who led the nation during a time of unprecedented industrial and economic growth.

* 1843 Born in Niles, Ohio

* 1861 Firing on Fort Sumter; Civil War began; McKinley enlisted in Union Army

* 1865 Civil War ended; Abraham Lincoln assassinated

* 1877 Compromise of 1877; Rutherford B. Hayes assumed presidency; McKinley elected to U.S. House of Representatives

* 1896 McKinley elected president of the United States

* 1898 Spanish-American War

* 1900 Boxer Rebellion in China; William McKinley re-elected president

* 1901 McKinley assassinated; Theodore Roosevelt became president

Early life and career

One of the most beloved of American presidents, William McKinley served during a time of unprecedented economic and industrial expansion. Born on January 29, 1843, in Niles, Ohio, the first truly modern president of the United States was the son of an iron founder who worked diligently to house, feed, clothe and educate his family. Placing a high value on education, his father moved the family to nearby Poland, Ohio, near Youngstown, when McKinley was nine years old, so that his son might attend a better school.

Enrolled in the local Poland Academy, McKinley was a good--though not a brilliant--high school student who succeeded by hard work. He developed an early interest in public speaking and took an active part in the debating clubs, eventually becoming president of the local debating society. In 1860, at the age of 17, he enrolled at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, where he remained for one year until lack of money and illness prevented the completion of his degree. Returning home to Poland, Ohio, McKinley went to work clerking in the post office and teaching school, hoping to earn money to complete his education; it would, however, be five years before McKinley resumed his studies, for the Civil War broke out in 1861.

McKinley was only 18 years old when Fort Sumter fell, but in the tradition of his great-grandfather who had fought in the Revolutionary War and his grandfather who had fought in the War of 1812, he enlisted in the 23d Ohio Volunteer Regiment under the command of Major Rutherford B. Hayes in June 1861. Made commissary sergeant, young McKinley distinguished himself at the battle of Antietam by serving a hot meal to troops under fire. Given a battlefield commission as second lieutenant, he quickly became the brigade quartermaster on Hayes's staff. In 1864, McKinley's gallantry in battle earned him the rank of captain. He was successively transferred to the staffs of Generals George Crook and Winfield S. Hancock, and, in March 1865, was promoted to brevet major for his bravery in the battles of Opequan, Cedar Creek, and Fishers Hill. When the war came to an end, McKinley was only 22, but his years in the military had transformed him from a skinny, frail 18 year old, to a healthy, mature young man. McKinley gave serious thought to remaining in the regular army, but other considerations changed his mind, and on July 26, 1865, Major McKinley was mustered out of the United States Army.

The most important question he then faced was what profession to enter. Not wanting to experience the unsteady day-to-day life of a merchant, McKinley chose to study law. After two years of reading in the office of Charles Glidden, a prominent attorney in the state of Ohio, McKinley entered Albany Law School. Admitted to the bar in March 1867, he opened an office in Canton, Ohio, later that year. Almost immediately, he plunged into politics and the Republican Party, working for his old commanding officer, Rutherford B. Hayes, in the Ohio gubernatorial campaign of 1867 and for Ulysses S. Grant in the presidential campaign of 1868. His hard work for the Republican Party paid off in 1869, when he was elected as the prosecuting attorney for Stark County, Ohio.

On January 25, 1871, McKinley married Ida Saxton, the daughter of Canton's leading banker; and within a year, the couple announced the birth of their first daughter Katherine. But while awaiting the arrival of a second child in 1873, Ida's mother died, and the extreme grief contributed to premature labor, complications, and the baby's death within a year. To compound the loss, their daughter Katherine contracted typhoid fever and died a few months later. As a result of her second pregnancy's complications, Ida McKinley never again enjoyed good health. Attempting to escape the trauma, McKinley looked for ways to channel his energies. In the midst of personal grief, politics proved therapeutic.

In 1876, after serving his political apprenticeship as prosecuting attorney, the 33-year-old McKinley was elected to Congress from the 17th Ohio district. Repeatedly re-elected, he served almost continuously for 15 years.

After his election to the United States House of Representatives, it became necessary for McKinley to take a solid stand on political issues. Two of the most gripping concerns were the silver and tariff questions. The first pitted advocates of bimetallism against proponents of the gold standard. Although never a defender of unrestricted inflation, McKinley favored the remonetization of silver. Aware of silver sentiment among his constituents, he sought some means of securing bimetallism without inflation and therefore surprisingly voted with the Democratic majority to pass the Bland-Allison Act of 1878 over the veto of President Hayes, authorizing limited silver purchases and instructing the treasury secretary either to coin the silver or to issue silver certificates.

Congressman McKinley Backs High Tariffs

The stand that won McKinley his solid reputation as a congressman, however, was not his vote on the silver issue, but rather his support of high protective tariffs. Upon entering Congress, McKinley wasted no time in making his position clear, insisting that until the United States was able to meet foreign competition, high tariffs were necessary to protect American industry. McKinley helped write a protectionist plank for the Republican platform of 1888, and after the Republican successes at the polls that year, he became chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. As author of the McKinley Tariff Act in 1890, he forced tariffs to new highs. The McKinley tariff contained three innovative provisions: first, to prevent the importation of wheat and other foodstuffs from Canada and Europe, it established a schedule of duties on agricultural products; second, in an attempt to satisfy consumer demand for lower sugar prices, it placed raw sugar on the free list; and third, it included a reciprocity section permitting the imposition of duties on products from Latin American countries that refused free entry to American products. McKinley believed that the high tariffs would save American industry. What he didn't envision were the effects on the American public and the ensuing turmoil.

The McKinley tariff, the high retail prices that the legislation caused, and lavish congressional expenditures brought on a backlash at the polls. Consequently, the election of 1890 brought a Democratic landslide while many Republican congressmen, including McKinley, lost their seats.

But as it turned out, the loss of his congressional seat may have been a blessing. Quickly rebounding, McKinley was nominated for governor in 1891 by the Ohio Republicans. For three months, he campaigned vigorously, making several speeches a day, and appearing in almost every one of the state's 88 counties. Elected governor by a narrow margin of votes, he was overwhelmingly re-elected two years later, indicating a successful administration. During his two terms as governor, the United States was gripped by one of the worst economic disasters in American history; McKinley, however, remained in Columbus in relative safety from political crucifixion as Grover Cleveland returned to the White House in 1893.

McKinley's growing prominence in the Republican Party had led to his serving as chairman of the Republican National Convention in 1892 and to his winning enough support to be mentioned as a presidential nominee. His respectable showing at the convention attracted the patronage of many prominent Republicans, led by Cleveland millionaire Mark Hanna, who were determined to help McKinley win the 1896 presidency.

To achieve national support, Hanna organized and financed a 10,000-mile trip through 17 states in which McKinley made nearly 400 speeches in eight weeks. The tour was so successful that by the time the Republican National Convention met in St. Louis in June 1896, McKinley had garnered enough support to be nominated on the first ballot. Garret A. Hobart of New Jersey was chosen as the vice presidential candidate.

Soon after the Republicans nominated McKinley, the Democrats selected William Jennings Bryan at their convention in Chicago. The People's Party, or the Populists, also selected Bryan as their candidate. Although McKinley was prepared to campaign on the issue of tariffs, the nomination of Bryan--an ardent free-silver advocate--changed the central issue of the campaign. McKinley dropped his advocacy of silver coinage and came out strongly for the gold standard, winning the support of President Cleveland and many other conservative Democrats.

Determined to take his cause to the people, Bryan traveled 18,000 miles, delivering 600 speeches to an estimated 5 million spectators, while McKinley remained at home in Canton, talking informally with a series of delegations brought in by the Republican campaign committee. By making sure that voters were aware of McKinley's political ideas, McKinley's campaign manager Mark Hanna developed a strategy that put Bryan and the Democrats on the defensive. The Republican campaign frightened bankers and businessmen by describing the inflation and federal controls on their businesses that would occur if Bryan were elected. While workmen were told factories would be closed under Bryan, banks were informing farmers that their payments would be extended at lower rates of interest under McKinley. At the campaign's close, Republicans had good reason to be optimistic. On election day, McKinley received 7,102,246 popular votes to Bryan's 6,492,559, and 271 to 176 electoral votes.

He Is Inaugurated as President

McKinley was inaugurated president on a mild, spring-like March 4, 1897. In his inaugural speech, he reviewed the problems of the depression that still gripped the country but noted the need to proceed cautiously while grappling with the situation.

Having assumed the responsibilities of office, McKinley immediately turned his attention to measures for assuring economic recovery. The tariff received first consideration, and McKinley's long experience in Congress aided him in pressuring for the legislation he wanted. He often called members of Congress to the White House and reasoned with them either to prevent the introduction of legislation he opposed or to win their support; as a result of such skillful negotiation, McKinley was forced to use the veto only 14 times during his administration. In March 1897, McKinley called a special session of Congress to deal with the tariff issue, and by July, Congress had passed the highest tariff in American history. Whether as a result of this legislation or natural progression, the economy turned upward.

As economic recovery set in, the nation's attention shifted its focus to Cuba, the center of Spain's New World empire and the richest of Spain's remaining possessions which had long suffered under an oppressive colonial system. A revolution had begun against the Spanish rule in 1894, but President Cleveland had avoided any American involvement. Whereas American popular sympathy was with the Cubans, McKinley's approach was cautious. In May 1897, he asked Congress for $50,000 for the relief of Americans stranded on the island. Two rival New York newspaper publishers, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, began to use the Cuban crisis to increase circulation, sending reporters to Cuba and playing up lurid stories of atrocities committed by the Spanish, promoting a brand of reporting that came to be known as "yellow journalism." Meanwhile, McKinley, still hoping to avoid war, wanted to intervene and act as a mediator between the Cubans and Spanish.

But two events in February 1898 moved the United States closer to war. On February 9, the New York Journal printed the contents of a private letter sent by the Spanish minister in Washington to a friend. The letter included insulting remarks about McKinley, describing him as a cheap, vacillating politician. A week later, the U.S. battleship Maine exploded while docked in Havana Harbor and sank with a loss of 266 lives. Shaken by the news, McKinley insisted on an official investigation. While the nation awaited the results, more and more people favored U.S. military intervention.

Unable to control the momentum sweeping the nation, McKinley too was swept up in the fervor. On April 11, he sent a message to Congress requesting that he be empowered to use the army and navy to intervene in Cuba. Finally, on April 25, the president asked Congress for a declaration of war against Spain. It was approved the same day.

Spanish-American War Begins

The Spanish-American War lasted less than four months. On May 1, Commodore George Dewey destroyed a Spanish fleet in Manila Harbor; on June 10, U.S. Marines landed at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; on July 3, the Spanish Caribbean fleet was destroyed at Santiago, Cuba. American troops landed in Puerto Rico on July 25, and the war ended with the unconditional surrender of the Philippines on August 15. American casualties totaled 1,941 with 298 killed. Another 5,000 died of disease. By December 1898, the American flag was flying over Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

The Philippines, however, were less than enthusiastic about being controlled by the United States. Again, they took up the fight for independence--this time against America. After a long and bloody conflict, U. S. forces finally put down the insurrection in 1902.

Chief among the other foreign affairs problems that challenged McKinley during his first term was a secret revolutionary society called the Boxers, who opposed McKinley's "Open Door" policy in China. McKinley wanted to promote trading opportunities in China, but the Boxers started a rebellion in 1900, with the intent of driving all foreigners out of their country. The president ordered U.S. Marines to join an international relief expedition with seven other nations, and the insurrection was put down in August 1900.

By mid-year 1900, McKinley had turned his focus from foreign policy to domestic events as he prepared for the 1900 presidential campaign. In June, he received the unanimous nomination for a second term as president from the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia. Garrett Hobart, McKinley's vice president, had died the previous November, and selecting the vice presidential candidate provided the only real excitement at the convention. McKinley originally asked Senator William B. Allison to consider becoming his running mate, but Allison refused. Finally, McKinley settled upon Theodore Roosevelt. The Democrats again chose Bryan as their candidate with Adlai E. Stevenson nominated as his running mate.

Seeking new campaign issues to add to tariffs and free silver, the Democrats accused the McKinley administration of being the tool of big business and demanded legislation to restrict trusts, while also accusing McKinley of a new imperialism, pointing to Cuba and the Philippines. Meanwhile, the president spent most of the campaign at his home in Canton, confident of victory. His confidence was justified. McKinley won the election with an impressive total of 7,218,491 votes to Bryan's 6,356,734 and an electoral vote of 292 to 155.

McKinley Is Assassinated

After his second inauguration, McKinley decided to go on a transcontinental tour intended to last six weeks; his wife became ill in California, however, and after she recovered, they spent the rest of the summer in Canton. Resting at home, McKinley concluded preparation of an address he was to deliver on September 5 at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. On September 6, 1901, the day after his address, McKinley stood in the exposition's Temple of Music shaking hands with a long line of well-wishers. A man by the name of Leon Czolgosz approached the president with his right hand wrapped in a handkerchief. As McKinley extended his hand, two shots were fired from a .32 caliber pistol concealed under the handkerchief. The president fell, grasping at his chest and abdomen.

Within minutes, McKinley was removed to the emergency hospital on the exposition's grounds. After physicians attended to his wounds, they had him removed to a private residence. For several days, he seemed to be recovering, but gangrene gradually set in and by September 13, his physicians abandoned hope.

Shortly before his death in the first hours of September 14, the president whispered to his wife, "Good-by all, good-by. It is God's way. His will be done." The nation went into deep mourning. As the funeral train bore the coffin from Buffalo to Washington for a state funeral and then to Canton for burial, millions lined the railroad tracks.