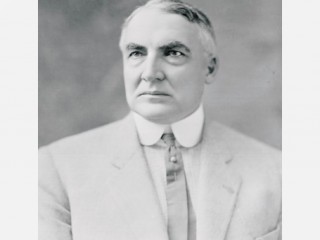

Warren G. Harding biography

Date of birth : 1865-11-02

Date of death : 1923-08-02

Birthplace : Corsica, Ohio, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-09-24

Credited as : Politician, former U.S. President,

4 votes so far

Warren G. Harding was born on Nov. 2, 1865, on a farm near Blooming Grove, Ohio. He attended local schools and graduated from Ohio Central College in 1882. His father moved the family to Marion that same year. After unsatisfactory attempts to teach, study law, and sell insurance, young Harding got a job on a local newspaper. In 1884 he purchased the struggling Marion Star with two partners (whom he later bought out). The growth of Marion and his own business skill and editorial abilities brought prosperity to the Star and to Harding. On July 8, 1891, he married Florence DeWolfe, a widow with one child; they had no children of their own.

Election to Office

Active in local Republican politics, Harding was elected in 1899 to the Ohio Senate, where he served two terms and became Republican floor leader. In 1903 he was elected lieutenant governor but retired in 1905. Although a born harmonizer who remained personally on good terms with all elements in the faction-ridden Ohio Republican party, he belonged to the Old Guard wing of the party. He ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1910. But in the Republican comeback in 1914 Harding was elected to the U.S. Senate. As a senator, Harding strongly supported business, pushing for high tariffs, favoring the return of the railroads to private hands, and denouncing radicals. He was a "strong reservationist" on the League of Nations, and he followed Ohio public opinion by voting for the prohibition amendment.

In 1919 Harding announced his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination; he won the nomination on the tenth ballot. Legend has pictured Harding as a puppet in the hands of his wife or his campaign manager. But Harding was no one's puppet: he was an ambitious and calculating politician. Nor was he the handpicked nominee of a group of Old Guard senators. The convention was unbossed, and Harding, with his reputation as a loyal party man, his amiable personality, and his avoidance of controversial stands, was the second choice of the majority of the rank-and-file delegates. When the two front-runners deadlocked, the convention had swung to the handsome Ohioan.

In the election Harding successfully straddled the explosive League of Nations issue. By capitalizing on the public's yearning for a return to "normalcy" after World War I, Harding won by the largest popular majority yet recorded.

The President

Despite the country's postwar position as a creditor nation, Harding gave his blessing to protective farm tariffs. Devoted to governmental economy, he supported establishment of the Bureau of the Budget, sharply cut government expenditures despite depressed economic conditions, and vetoed the World War I veterans' bonus passed by Congress. He backed Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon's program for repealing the excess-profits tax and lowering the income tax on the wealthy; he gave Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover a free hand in his efforts to promote business cooperation and efficiency; he favored turning over government-owned plants to private enterprise; he packed regulatory commissions and the Supreme Court with conservative appointees; and he strongly favored immigration restriction.

Harding wished to remain neutral in labor disputes and worked behind the scenes for conciliation, but when his hand was forced, he took management's side. Thus, after his attempted mediation in the 1922 railroad shopmen's strike failed, he approved a sweeping injunction against the strikers--this won him the bitter enmity of organized labor.

But Harding was not the archreactionary of later myth. He supported the Sheppard-Towner Act (1921), extending federal aid to the states to reduce infant mortality. He unsuccessfully proposed establishing a department of public welfare to coordinate and expand Federal programs in education, public health, child welfare, and recreation. He was instrumental in ending the 12-hour day in the steel industry. He promoted increased federal spending on highways. He commuted the sentences of most of the wartime political prisoners, including Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs. While balking at government subsidies or price-fixing to assist farmers hard hit by postwar falling prices, he approved legislation for extending credit to farmers, for stricter federal supervision of the meat industry, for regulating speculation on the grain exchanges, and for exempting farm marketing cooperatives from the antitrust laws.

Foreign Policy

In foreign policy Harding was largely guided by his prointernationalist secretary of state, Charles Evans Hughes. Although Harding regarded the 1920 election as a popular mandate against American membership in the League of Nations, his administration cooperated with the nonpolitical activities of the League, and in 1923 he came out in favor of American membership on the World Court. Adamant in demanding full repayment of Allied war debts, he was flexible in arranging terms.

Efforts were made to restore good relations with Mexico and Cuba and to terminate military intervention in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Colombia was indemnified for the loss of Panama. The Harding administration's most important diplomatic achievement was the Washington Conference. Meeting in November 1921, the conferees formulated a series of treaties, which secured Senate ratification, fixing ratios of warships for the United States, Britain, Japan, France, and Italy, guaranteeing the territorial status quo in the Pacific, and reaffirming the independence and territorial integrity of China and the open-door principle of commercial equality.

Scandals in the Administration

By 1923 Harding was increasingly disturbed by the rumors of corruption involving high administration officials and hangers-on. But he failed to act decisively, partly because he believed the attacks were politically motivated, partly because of a misplaced loyalty to old friends. Perhaps his worst mistake was in appointing his senatorial crony Albert B. Fall as secretary of the interior. Fall persuaded Harding to transfer naval oil reserves from the Navy Department to the Department of the Interior. Then, after Fall had corruptly leased the reserves at Elk Hills, Calif., and Teapot Dome, Wyo., to oilmen, he induced Harding to defend these transactions when questions were raised in the Senate.

Although the Republicans had suffered sharp losses in the 1922 congressional elections, Harding personally remained tremendously popular. However, his health was affected by overwork and anxiety over his wife's health and the multiplying evidences of corruption in his administration. He suffered a heart attack followed by bronchopneumonia while on his cross-country tour in the summer of 1923. He died on Aug. 2, 1923, probably from a cerebral hemorrhage. The posthumous exposure of the scandals in Harding's administration--including Fall's conviction for bribery, the attorney general's forced resignation and narrow escape from jail, and prison sentences for the head of two government bureaus--and the charges that Harding had fathered an illegitimate daughter and that he drank excessively all led to his decline in public esteem.

Yet Harding was not the affable, weak, and even stupid figure of popular legend. He was a hardworking, conscientious, well-intentioned, politically skillful chief executive who was not without courage or the capacity for growth. Most contemporaries praised his success in leading the country through the painful transition from the difficulties of the postwar years, and his administration did lay foundations for later prosperity. But he showed indecisiveness and lack of leadership when faced with conflict; his mind was untrained and undisciplined; and most important, the values of small-town America which he embodied were inadequate for dealing with the problems of the postwar world.