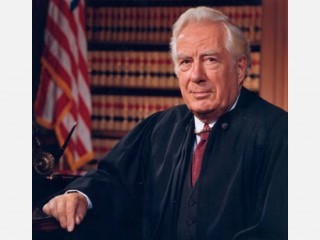

Warren E. Burger biography

Date of birth : 1907-09-17

Date of death : 1995-06-25

Birthplace : St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-08-25

Credited as : Lawyer, Supreme Court Justice,

3 votes so far

An early interest in law

Warren E. Burger was born on September 17, 1907, in St. Paul, Minnesota. He was the fourth of seven children born to Charles Joseph Burger, a railroad cargo inspector and traveling salesman, and Katherine (Schnittger) Burger, a homemaker. The family struggled to make ends meet, and by age nine Burger was delivering newspapers to help out. As a fourth-grader, he became ill and missed a year of school. During this time, he began reading law books and biographies of American historical figures.

Unable to attend Princeton because of his family's limited resources, Burger took courses at the University of Minnesota for two years and then enrolled in a night law school. Combining study with work as a life insurance salesman, he earned his law degree from St. Paul College of Law in 1931. He then joined a law firm in St. Paul. In addition to handling a variety of civil and criminal cases, he taught contract law at St. Paul College of Law for a dozen years. On November 8, 1933, he married Elvera Stromberg, a fellow student from the University of Minnesota.

Political career

Burger became active in Republican politics and helped organize the Minnesota Young Republicans in 1934. He played an important role in the successful 1938 campaign for governor of Harold Stassen (1907–2001). At both the 1948 and 1952 Republican National Conventions, Burger acted as a manager for Stassen's unsuccessful presidential campaign. During the 1952 gathering Burger supported Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), helping him win the presidential election.

After the election President Eisenhower made Burger head of the Justice Department's Civil Division. Burger supervised a staff of approximately 180 lawyers. Although he had almost no experience in maritime law (law involving goods that are transported on the seas), Burger successfully handled several cases involving shipping for the government and even helped end a dockworker's strike on the East Coast in 1953.

Law and order judge

In 1955 Eisenhower named Burger to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. While on that bench, Burger wrote several articles and gave lectures on a variety of topics. His opinions on criminal cases attracted attention. He said that confessions should be admitted into evidence even when the police have broken legal rules in obtaining them. He also argued that physical evidence should be allowed even if it has been obtained through forcible entry (forced entry without legal permission).

During the 1968 presidential campaign, Richard Nixon (1913–1994) told a public worried about the rising crime rate that the Supreme Court was "seriously hamstringing the peace forces in our society and strengthening the criminal forces." In other words, the court was making decisions that made it difficult to enforce laws and was thus helping criminals. He promised, if elected, to ensure that the court would no longer stand in the way of law enforcement (the people and government agencies that work to catch and punish criminals). The victorious Nixon's first step toward that goal was appointing Burger to succeed Earl Warren (1891–1974) as chief justice. In Burger's most famous criminal case, the loser was the president. In 1974 Burger ordered Nixon to turn over tape recordings to Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski (1905–1982). These tapes contained evidence that Nixon had committed a crime. This ruling led directly to the president's decision to leave office before the end of his term.

In more routine criminal cases, Burger as chief justice was everything Nixon had hoped for. Burger led the court in a series of decisions that went against Warren court rulings. In Harris v. New York (1971), he announced that a statement obtained without reading a suspect his or her rights as required by Miranda v. Arizona (1966) could be used in court cases. Burger also helped give new life to the death penalty, which had been legalized again by the court in 1976 but was rarely carried out. With the chief justice lashing out at lawyers who used whatever methods they could to keep their clients alive, the Supreme Court rejected almost all appeals in such cases. (In an appeal, a case or a decision in a case is reviewed by a higher court.) Executions began to occur with greater frequency.

Civil rights and liberties

Burger was less sympathetic toward civil liberties claims than Earl Warren had been. Despite having worked in Minnesota with groups seeking to improve race relations, his rulings on civil rights were inconsistent—some for, some against. Burger's decisions on matters involving the First Amendment's establishment of religion clause were also inconsistent. He urged strict separation between church and state in one case involving state funding to assist religious schools, but in two other cases he supported the presence of religion in state functions: He upheld Nebraska's practice of opening legislative sessions with a prayer delivered by a state-paid Protestant chaplain, as well as the right of the town of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, to display a nativity scene in front of its city hall.

Burger also made it more difficult for civil rights and civil liberties claims to be decided on in federal court. The Burger court increased the number of officials who could not be sued (have a law suit brought against them) for damages (payment to a person or people who suffered a loss or an injury) for violating citizens' constitutional rights. The court also made it more difficult for citizens to file class-action suits, lawsuits in which one or more persons sue on behalf of a large group whose members have suffered an injustice or inequality.

Legacy of reform

Despite being less receptive to civil rights and civil liberties claims, the Burger court was not as different from the Warren court as some people expected it to be. Although often critical of the work of the Warren court, the Burger court did not undo it. None of the Warren court's major decisions was reversed. Even in the area of criminal law, the Burger court limited the effect of, rather than overturned, Warren court rulings.

After seventeen years on the court Burger had been responsible for many reforms and improvements in the justice process. At his suggestion many courts began to employ professional administrators (people who supervise the way a court runs), and an institute was set up to train them. Burger was in favor of continuing education for judges. His attacks on the abilities of trial lawyers inspired improvements in their training. He also improved the working relationship between federal courts and state courts that served the same geographic areas. In 1986 Burger resigned as chief justice to work full time as head of the U.S. Constitution Bicentennial Commission. He was also chancellor, or chief officer, of the College of William and Mary, from 1986 to 1993. Warren Burger died in Washington, D.C., on June 25, 1995.