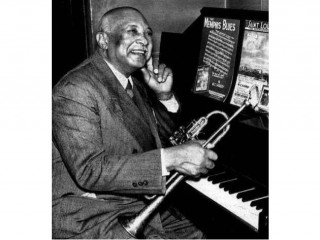

W.C. Handy biography

Date of birth : 1873-11-16

Date of death : 1958-03-28

Birthplace : Florence, Alabama, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-11-28

Credited as : blues composer, "Father of the Blues".,

5 votes so far

W. C. Handy's remarkable life started eight years after the conclusion of the American Civil War. Born in a log cabin in Florence, Alabama, on November 16, 1873, William Christopher Handy entered into a new era for black people--an era that he himself would help define by introducing his people's music to the world. He thereby became the "Father of the Blues."

The predecessors of the blues were around long before Handy ever picked up a cornet, but they had no name. They were the "folk music" songs of black-American slaves, sung as a deeply emotional and personal response to the brutality and desperation of their lives. It was an undefined sound that was derived from the varied African cultures touched by the slave trade, a sound rooted in firm African traditions carried halfway across the world. It was the song of the poorest of the poor, even among slaves, and it belonged to the most illiterate and forgotten, the so-called "cornfield niggers."

As a trained musician Handy would come to recognize what he once regarded "primitive" as a viable form of music. He sought a way to translate the blues into compositional form. He set about codifying it: a three-line, 12-bar pattern, with flat third or "blue" note. Though there is a recipe for the blues, its quality is elusive. The fine points of timing and the subtle vocal and pitch variations are essential. It is generally regarded as a music that is deceivingly simple and too easily unappreciated by the untrained ear.

Handy's parents and grandparents were among the four million slaves freed by President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. One in a sea of liberated souls, his paternal grandfather, William Wise Handy, became a well-respected citizen of Florence and the Methodist minister of his own church. Handy's father followed in those footsteps, and the same future was planned for the young Handy. It was the boy's maternal grandmother who hit upon his destiny by suggesting that her grandson's big ears symbolized a talent for music.

The words thrilled him. At the age of 12, he fell in love with a guitar in a shop window, and one day, after counting out the salvaged earnings from his string of odd jobs, he was finally able to take his prize home. According to Handy's autobiography, Father of the Blues, his parents were shocked and dismayed by his interest in the guitar. His outraged father apparently demanded that he return the "devil's plaything" and exchange it for "something that'll do you some good." The bewildered boy traded it in for a new Webster's Unabridged Dictionary-- and his father paid for organ lessons.

Handy received his education in the rudiments of music during his 11 years at the Florence District School for Negroes. His teacher was a lover of vocal music and took time to give his students voice and music instructions that would enable them to sing religious material--without the accompaniment of instruments. The students were introduced to works by classical composers such as Wilhelm Richard Wagner, Georges Bizet, and Giuseppe Verdi. They learned to sing in all keys, measures, and movements. But Handy longed to play instruments, so on the sly he bought an old cornet and took lessons from its former owner.

At age 15, Handy joined a minstrel show and began his musical career. But after touring only a few towns, the troupe fell apart, and the teenager found himself walking the railroad tracks back to Florence. In 1892, after graduating from the Huntsville Teachers Agricultural and Mechanical College and squeezing in a summer of teaching experience, he arrived in Birmingham to take the teachers' examination. But when he heard that he could expect a salary of $25 or less per month, it didn't take him long to opt for a job at a pipeworks company in the city of Bessemer instead. When wages there were cut, Handy returned to Birmingham, where he organized the Lauzette Quartet. At the announcement of the Chicago World's Fair, the quartet boarded a tank car and, with only 20 cents between them, headed for fame. But once in Chicago they learned that the fair had been postponed for a year. The dejected band traveled south to St. Louis, Missouri, where they were soon forced to break up. The country was experiencing an economy in panic. The St. Louis days would imprint themselves on W. C. Handy's mind and music. They would bring the educated son of a minister closer to the experience of the downtrodden negro. Surrounded by misery and opulence alike, the young black man suffered from hunger and lice, slept in a vacant lot, slumped in a poolroom chair, in a horse's stall, and on the cobblestones of the levee of the Mississippi. As he related in his autobiography, his inner voice said repeatedly, "Your father was right, your proper place is in the ministry," and his old schoolteacher's words rang through his head, "What can music do but bring you to the gutter?," but he never gave in. The musician continued to eke out a living playing his cornet and later noted that these down-and-out days would lead to the birth of his "St. Louis Blues."

It was in Evansville, Kentucky, that Handy first gained popular attention. While playing with several local brass bands, word about his talent spread to Henderson, Kentucky, and he was soon hired by its Southern aristocracy. "I had my change that day in Henderson," Handy wrote in his autobiography. "My change was from a hobo and a member of a road gang to a professional musician." In Henderson, Handy also found another opportunity to expand his music education. He angled a job as a janitor in a German singing society only to get close to its director, a professor who was an accomplished teacher, music director, and author of several successful operas. Handy pounced on his every word: "I obtained a post-graduate course in vocal music--and got paid for it," he proclaimed. It was also in that town that Handy met and married his first wife, Elizabeth Virginia Price.

In 1896, Handy was invited to Chicago to join W. A. Mahara's Minstrels, a move he would look back at as "the big moment that was to shape my course in life." As bandleader and soloist he toured with the Minstrels from 1896 to 1900 and again from 1902 to 1904. In the years between he was music teacher and bandmaster at his old college in Huntsville. The Minstrels had an adventurous on-the-road history together, crisscrossing the South and traveling as far as Cuba. When the band had an engagement in Alabama, Handy Sr. took in the show. The minister evidently had a change of heart: "Sonny," he said, as recounted in Father of the Blues, "I haven't been in a show since I professed religion. I enjoyed it. I am very proud of you and forgive you for becoming a musician." Welcome words from the man who once told his young son that he'd rather follow his hearse than see him follow music.

The year was 1909 and Edward H. "Boss" Crump was running for mayor of Memphis. He needed a campaign band. Handy's group was hired, and "Mr. Crump," the campaign song, came to be. Handy had written it without words but soon--without the reformist candidate's knowledge--the song included lyrics based upon spontaneous comments from the disgruntled crowd: "Mr. Crump won't 'low no easy riders here/Mr. Crump won't 'low no easy riders here/We don't care what Mr. Crump don't 'low/We gon'to bar'l-house anyhow--/Mr. Crump can go and catch hisself some air!"

Crump was elected--perhaps in spite of the song--and the campaign tune was to meet its end, but by that time it had gained such popularity that Handy decided to have it published. He changed the embarrassing lyrics, and "Mr. Crump" turned into "Memphis Blues." Handy entered into an agreement with two white men. One was to arrange the printing and the other, who owned a music publishing company and a record store, would take care of the distribution.

After repeated rejections from stores, the defeated Handy agreed to cover his costs and sell the copyright of "Memphis Blues" to the second man for $50. What Handy did not know then was that the "exploiter," as the musician referred to him in his autobiography, had printed twice the agreed-upon number of records and was successfully distributing them in the North. Despite the injustice, the copyright of "Memphis Blues" marked the first time that the blues had ever been set in print.

Melancholy about the growing popularity of a song that was no longer his, Handy started searching for a second hit. He holed himself up in a rented room and set to work. Snatches of street life drifted in through the window. "Ma man's got a heart like a rock cast in the sea," is said to have come from the lips of a drunken black woman stumbling down the dimly lit street. The mournful words worked their way into his soul and triggered the flood of memories of his own lost and hungry St. Louis days. He wrote, "I hate to see de evenin sun go down," and between midnight and dawn, a classic--"St. Louis Blues"--was born.

"St. Louis Blues" was followed by a flurry of other compositions, including "Jogo Blues," "Yellow Dog Blues," "Joe Turner Blues," and "Beale Street Blues." In 1908, Handy and Harry H. Pace, a singer and songwriter, created the Pace & Handy Music Company. The company soon thrived. Handy and the blues were on their way.

Handy found that he could no longer endure the rising racial tensions in the South. In 1918, the year that saw the end of World War I, the Pace & Handy Music Company moved to Manhattan. After two years of popular if not monetary success, Pace decided to pull out and go in his own direction. Pace & Handy was renamed Handy Brothers Music Company and can still be found at the same Broadway address today. Throughout his life Handy was troubled with failing eyesight, and it was at this fiscally shaky time that he went totally blind. But it was a temporary condition. He regained his sight and composed "Aunt Hagar's Children Blues," which turned out to be the hit that put him on a solid financial ground. In 1926, Handy edited Blues: An Anthology. His public continued to grow, and the blues gathered speed.

In 1928, Carnegie Hall witnessed its first evening of black music. By entering this bastion of white classical music, W. C. Handy and the blues stepped arm-in-arm into the limelight, and half a century later, his daughter, Katherine Handy Lewis, would be back at the Hall to sing at the 1981 recreation of that historic milestone. The World War II years continued to be productive and brought increased fame to Handy. He even managed to heal an old disappointment by being honored at the 1940 New York World's Fair. A year later the composer told his story in his autobiography, Father of the Blues, and then in 1958, he was portrayed by Nat King Cole in Paramount's St. Louis Blues, a film based on his life. Streets and parks from Alabama to Memphis to New York were named after him. The "Father of the Blues" has remained a beloved public figure decades after his death in 1958.

Handy's life was a rich one, but it was not untouched by sorrow. In 1937, his beloved wife, Elizabeth, died of a cerebral hemorrhage. Years earlier the couple had lost one of their six children, and in 1943 Handy himself came perilously close to death after falling off a New York City subway platform and fracturing his skull. The accident left him blind and bound to a wheelchair for the remainder of his life.

Following publication of his autobiography, Handy published a book on African-American musicians entitled Unsung Americans Sing (1944). He wrote a total of five books:

-Blues: An Anthology: Complete Words and Music of 53 Great Songs

-Book of Negro Spirituals

-Father of the Blues: An Autobiography

-Unsung Americans Sing

-Negro Authors and Composers of the United States

After the death of his first wife, he remarried in 1954, at age 80. His new bride was his secretary Irma Louise Logan, whom he frequently said had become his eyes.

In 1955 Handy suffered a stroke, following which he began to use a wheelchair. Over 800 people attended his 84th birthday party at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

On March 28, 1958 he died of bronchial pneumonia at Sydenham Hospital in New York City. Over 25,000 people attended his funeral in Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church. Over 150,000 people gathered in the streets near the church to pay their respects. He was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York.

The composer of more than 80 hymns, marches, and blues tunes, W. C. Handy did more to carry the blues into the mainstream of music than any other man. His contribution is a legacy that has exerted a profound and lasting influence on twentieth-century music--a legacy that includes rock 'n roll, which was an offshoot of Chicago's electrified blues. It was Handy's background of solid education and training in classical music that set him apart from his fellow black musicians. It seems to have taken someone with a foot in each world to open the door between them and let the blues come in.

Selective Works

"Memphis Blues" (originally "Mr. Crump," 1909), Handy Brothers Music Co., 1912.

"Jogo Blues," Handy Brothers Music Co., 1913.

"Yellow Dog Blues," Handy Brothers Music Co., 1914.

"St. Louis Blues," Varsity, 1914.

"Hesitating Blues," Handy Brothers Music Co., 1915.

"Joe Turner Blues," Robbins Music Corp., 1915.

"Beale Street Blues," Handy Brothers Music Co., 1917.

"Aunt Hagar's Children Blues," Handy Brothers Music Co., 1921.

"Loveless Love" (better known as "Careless Love"), Varsity, 1921.