Utah Phillips biography

Date of birth : 1935-05-15

Date of death : 2008-05-23

Birthplace : Cleveland, Ohio,U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-01-10

Credited as : Singer, Folk singer, the Golden Voice of the Great Southwest

0 votes so far

One of the last living examples of an American folk musician who learned his trade as he wandered the country's highways and byways, Utah Phillips has spent a lifetime singing songs and telling stories of working people. A longtime labor organizer and peace activist, Phillips also appeals to lovers of the railroads, for he has composed numerous songs about that historically rich form of transportation. Add his skills as an entertainer to his colorful background and his righteous spirit of commitment, and the result is an American institution who gained the attention of a whole new generation when he began recording with the hard-edged punk-folk performer Ani DiFranco in the 1990s.

Bruce Phillips was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on May 15, 1935. His parents were labor organizers. They later divorced, and he moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, with his mother in 1947. Learning to play the ukulele from an instruction manual, he took to the roads and rails of the West as a teenager. "I worked with lots of old drunks only fit to shovel gravel, but they all knew songs, and they showed me how to play them," he told Scott Alarik of the Boston Globe. "The reason I wound up doing what I do now, I guess, was that the songs these guys sang were so close to their lives, to what they were experiencing in their work and loves and afflictions." Phillips also liked the country music of the day and took the name U. Utah Phillips in emulation of country vocalist T. Texas Tyler. He continued to use the name Bruce in nonperformance situations.

Phillips worked for a printer and held other odd jobs. He joined the radical International Workers of the World labor union and did organizing work for them. At one financial low point in 1956, Phillips enlisted in the Army and was sent to Korea for three years. "I wanted to learn a trade, but all they taught me was how to shoot," he said in a Sing Out interview quoted on the website of the Folk Alliance organization. "What I really learned in the army was how to be a pacifist." When he returned from Korea, he told Eric Reiner of the Denver Post, "I was so mad at what I'd seen and done that I got on a freight train in Everett, Washington, and rode for about two years." One of his first songs, "Enola Gay," dealt with the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan at the end of World War II.

Back in Salt Lake City, Phillips took a job with the Utah State Archives. His radicalism grew alongside that of other younger Americans in the 1960s, and he worked for left-wing Catholic priest Ammon Hennacy at Salt Lake City's Joe Hill House, a place of hospitality for tramps and itinerant workers. In 1968 he ran for the U.S. Senate as a candidate of the Peace and Freedom Party. The several thousand votes he received were respectable for a third-party candidate, but the race cost Phillips his state government job.

Unsure of what to do next, he turned to music (although his political ambitions resurfaced in a 1976 run for president of the United States on an anarchist platform). Musician Tut Taylor brought some of Phillips's songs to a Nashville music publisher, and they found takers: bluegrass duo Flatt & Scruggs recorded his train song "Starlight on the Rails," and Joan Baez became the first of many to record the dark romantic ballad "Rock Salt and Nails," a song that became something of a folk and country standard.

Phillips had no desire to become part of the Music City assembly line, however, and especially later in life he became leery of having country performers record his music. In 1970 he began exploring a different part of the music world when Utah-born singer Rosalie Sorrels asked him to appear with her at the Caffe Lena folk coffeehouse in Saratoga Springs, New York. Phillips warmed gradually to this new scene, soon realizing that it fit both the musical and activist sides of his background. "I was writing and learning songs, working on my act, learning to book gigs," he recalled to Alarik. "It took me a year to realize I was not an unemployed organizer; I was a folk singer."

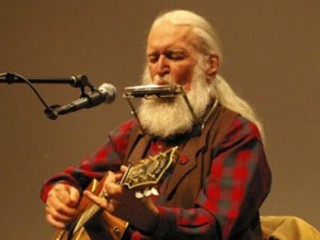

Phillips performed at small clubs and coffeehouses and recorded occasionally for the Philo label. In the process, he became one of the folk world's best-loved figures. He applied his union organizing skills to the world of music, building up a durable grassroots network of folk music presenters who had a strong volunteer involvement. Phillips became something of a one-man clearinghouse for folk music resources and advice, and his shows were keenly attuned to his audiences. He researched the local lore of each place he visited, tailoring his stories to the history and industry of the area, and he traveled with different colors of his trademark flannel shirt, to ensure a sharp contrast with the backdrops at each venue. His bushy white beard grew into another signature look.

With a fan base that ranged from the folk hard core to railroad and Western buffs, Phillips enjoyed an unusually long career. Just when he might have been slowed by a congestive heart failure diagnosis in the mid-1990s, he was introduced to a new set of listeners through the efforts of Ani DiFranco, who edited about 100 hours of tapes of his performances--Phillips encouraged audiences to tape his shows--into an album called The Past Didn't Go Anywhere (1996), and released it on her own Righteous Babe label, adding acoustic and electronic accompaniment to Phillips's voice. The 29-year-old DiFranco and the 64-year-old Phillips found plenty of common ground, and collaborated on a new live album, Fellow Workers, in 1998. Phillips sang at DiFranco's wedding, and DiFranco, writing in England's Observer newspaper, enthused that "one thing we really connect on is this wedding of political range and humor and joy."

The collaboration, which was planned to extend to a third album, brought Phillips new attention. In 1999 the Red House label issued The Moscow Hold, another compilation of Phillips's concert tapes; other retrospectives of his work appeared, and he was given awards by music and labor groups. Residing in Nevada City, California, in 2005, he became involved in a project to bring together a network of churches to house the area's homeless population. Phillips spoke out against both Iraq wars and recorded a new song, "Talking NPR Blues," that took aim at what he saw as public radio's increasing corporatization. He hosted a syndicated radio program of his own, Loafer's Glory, that ran for 100 episodes. Still performing occasionally as he reached the age of 70, Phillips has remained an activist and an individualist in a grand American tradition.