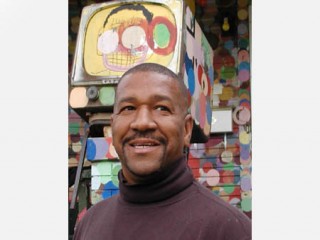

Tyree Guyton biography

Date of birth : 1955-08-24

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Detroit, Michighan, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-28

Credited as : Artist, Heidelberg Project ,

13 votes so far

Artist Tyree Guyton has proven the old adage that "one man's trash is another man's treasure" by transforming his blighted Detroit neighborhood into a thriving indoor/outdoor art gallery. Guyton began his Heidelberg Project over twenty years ago by taking discarded objects he found--everything from old shoes to bicycles to used tires to baby dolls--and using them to embellish abandoned houses, sidewalks, and empty lots. At first, city leaders called his art junk and took a bulldozer to it. Now, however, Guyton is recognized worldwide as an "urban environmental artist" who helps revitalize economically depressed communities through the power of art.

Through his work Guyton has challenged the boundaries between art and life, as did French artist Marcel Duchamp, who took ordinary objects and presented them as art, and American artist Robert Rauschenberg, who combined painting and common objects in collages or "combines." Guyton's work falls outside what is commonly recognized as art. Part of a group of "outsider" artists--Western artists who draw inspiration from sources outside traditional art--Guyton draws from the lives of the urban poor and makes their experiences and human spirit visible to people who have come from all over the world to see his work. He also shows how fragments of city life can be turned into art.

Guyton was born in 1955 in Detroit, Michigan, one of ten children raised by his mother. The east side neighborhood where he grew up was not always rough; at one time it was "really beautiful, with well-kept houses on all the lots and happy kids playing in the street," Guyton told Brad Darrach in People. When he was twelve, however, a violent race riot spread through the city. After five days, there were forty-three dead, over 400 injured, and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed by fire. In the aftermath, residents and businesses fled the city for the suburbs, leaving many neighborhoods filled with abandoned homes. Those residents who remained were often too poor to move from the troubled region, and had to deal with dilapidated schools and escalating drug and gang activity.

Artistic Beginnings

Growing up in one such neighborhood, Guyton found his escape in creativity. "When I was a kid, all I had was the art," he told Janet I. Martineau on the MLive Saginaw News Blog. "It was my safe haven, my rescuer." His grandfather nurtured young Tyree's artistic inclinations. "Grandpa was a housepainter," Guyton told Darrach. "When I was eight years old, he stuck a paintbrush in my hand. I felt as if I was holding a magic wand." It was his mother, however, who influenced Guyton's graphic style. Because their family was poor, he remarked to Darrach, "Clothes, furniture, everything came from a second-hand store or was given to us. On the floor we had squares of linoleum. On the sofa were stripes. On a chair there were polka dots. Nothing matched, but my mother made it work. Today I paint with stripes and polka dots, and it works too."

As a teenager Guyton attended Northern High School. To further his art education, he took adult art classes at high schools and colleges in Detroit, including the Center for Creative Studies, the Franklin Adult Education Program, and Marygrove College. He also received early encouragement from Detroit artists Charles and Ali McGee. After serving in the U.S. Army for two years in the early 1970s, Guyton supported himself by working as an inspector for the Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, serving as a firefighter with the Detroit fire department, and teaching art at his old high school. However, he continued to think about making art, and with the encouragement of his grandfather, he decided to do just that.

In the mid-1980s Guyton began the Heidelberg Project, named after the street where he starting building. In his neighborhood, with its abandoned, drug-infested houses, he gathered discarded objects and used them to decorate the outsides of the houses or make roadside sculptures, transforming his collections into urban art. With the help of his grandfather, Sam Mackey, and first wife Karen Smith, Guyton painted the objects he attached to the exteriors of the houses and surrounded them with everything from tires to toilets to tombstones, depending on his theme for the house. He also filled empty lots with rows of drinking fountains and old appliances. The painted polka dots that became his signature were inspired by his grandfather's love of jelly beans.

Guyton's urban art gallery changed the city blocks on which it was located from deserted combat zones to places where people stopped and stared. In his essay in the book Art in the Public Interest, Michael Hall observed: "A stroll down Heidelberg Street (despite the rawness of Detroit's East Side) recalls a stroll down the main street of Disneyland. Guyton, like Disney, delights, entertains and beguiles with his fantasy facades." Part of the fascination surrounding Guyton's works is that they were forever changing due to weather or the environment, or through the artist's whims. The artist saw the attention as something positive. Pointing to one of his works, a former crack house, he remarked to Darrach, "After the fourth [police] raid we couldn't stand it anymore. So we went on over and painted the place. Pink, blue, yellow, white and purple dots and stripes and squares all over it. Up there on the roof we stuck a baby doll and that bright blue inner tube, and on the porch we put a doghouse with a watchdog inside.... Now all day long people drive by and stop to stare at the place. Believe me, in front of an audience like that, nobody's going to sell crack out of that house anymore."

Controversy over Heidelburg

Initial public reaction to Guyton's offbeat street works generated considerable controversy in his home city of Detroit. Some neighborhood residents viewed them as eyesores, and the artist was ticketed for littering. In addition, after reported complaints by neighborhood residents reached the ears of Detroit's then-mayor, Coleman Young, four of the abandoned houses Guyton had decorated with objects were suddenly demolished by the city government in 1991. A second demolition occurred in 1999, during the mayoral administration of Dennis Archer. Guyton sued the city for the destruction of his work, but the suit was later dropped when he came to an accommodation with the city government in the early 2000s.

Guyton believed that at least one of these houses, The Babydoll House, which, through its use of broken, naked dolls, dealt directly with issues of child abuse, abortion, and prostitution, was demolished because its images were so powerful. The artworks stored in the fallen houses--estimated to be worth as much as 250,000 dollars, based on what Guyton's work was selling for at the time--had been scheduled to be part of an art tour sponsored by the Detroit Council for the Arts. "Each doll represents something," Guyton told a contributor in the Toronto Globe and Mail. "They tell the horrors of drugs and the pity of a neglected child."

Guyton has continued to respond to those who have questioned his motives in creating such controversial works. "This is my art," he maintained to Peter Plagens in Newsweek. "Most of the things used are things that I didn't have coming up. We didn't have a phone, we didn't have toys to play with. So a lot of the stuff that I relate to is stuff that has played a part in my life--stuff that I didn't have, stuff that I wanted." Guyton also noted that his art is driven by his need to "talk about life here in this area ... to talk about the craziness." Many critics agree that his work, while unconventional, is nonetheless art; as Art News contributor Sandra Yolles commented, "Guyton's compositions consist of the houses, the vacant lots, the streets, the trees, the telephone poles. The power of his imagery is what touches people--so much so they have composed music about it, held concerts around the works, and given money for new projects." In an essay for the Detroit Institute of Arts Ongoing Michigan Artists Program, Marion E. Jackson compared Guyton's work to the folk-art "bottle trees" made by African-American artists in the South. The critic added: "The fragmentation, isolation, and juxtaposition of the familiar with the unfamiliar may even affect us subliminally," while "difficult themes such as abortion, child abuse, homelessness, and abandonment" become "jarring aspects of a complex and ever-changing mosaic."

The initial controversy surrounding the Heidelberg Project also brought Guyton international attention. His work was featured on a segment of the NBC Nightly News and Guyton himself has appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show and Good Morning America. As news of his work spread beyond Detroit, visitors from New York City, Canada and even Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Japan began coming to view the project. When Jenenne Whitfield (whom Guyton married in 2001) joined the project as executive director in 1993, it began a period of community outreach for Guyton and his work. He began hosting street festivals and participating in exhibitions and projects worldwide. In Detroit, the Heidelberg Project spread to cover two city blocks, as the nonprofit organization purchased abandoned homes to be decorated with Guyton's art.

Reaching Out to the Community

Guyton found himself in demand as an artist and community organizer. In 1996 he was invited to St. Paul, Minnesota, to transform the outside of a house belonging to the widow of the University of Minnesota's former president as part of an exhibition for the Minnesota Museum of American Art. "We live in a time where art can be anything and everything," Guyton told Joe Kimball in the Minneapolis Star Tribune. "It's time to shock people back into reality, to make people think. They look at this and think: Can he really do that? Yes?" In 2001, the artist was invited to create a permanent art installation for the city of Mt. Vernon, New York. In conjunction with a local art center and groups of teenagers and senior citizens, the Circle of Life was created to show "that art can be a catalyst [for] social change and leadership" by "making the connection between life and art," Lisa Robb commented in the Westchester County Business Journal.

Guyton continued to broaden the reach of his Heidelberg Project in the 2000s. Although some critics contended that his work would not be accepted in wealthier, surrounding suburban neighborhoods, in 2002 he was invited to transform a house in a Detroit suburb into a temporary art exhibition. He used polka dots, old shoes and toys, and collaborated with local artists and schoolchildren. The result was "an ephemeral but memorable artwork--jolly, colourful and idiosyncratic," remarked a contributor in the Architectural Review. In 2004 Guyton flew halfway across the world to create artwork in Sydney, Australia. He worked with a diverse group of residents, including aboriginal youth, to transform a school, community center, and skateboard park into a project called Singing for That Country. "I am honored to have been invited to play a role in Singing for That Country," the artist was quoted as commenting in PR Newswire. "If we are capable of landing on the moon, building weapons of mass destruction and fighting wars, I say we are also capable of bringing hope, health and happiness to people all over the world."

Guyton continues to develop his art in his hometown of Detroit as well. In 2003 he began developing The House That Makes Sense, a new project to cover a house entirely with pennies, in collaboration with an architectural firm and Youthbuild Detroit, a nonprofit working with young people to help improve their communities. "I want to build a place where kids can come to learn, to be themselves and to see that there are opportunities for them beyond this neighborhood," Guyton told David Lyman in the Detroit Free Press. When finished, the house will include a workshop for young artists, a space where their art can be exhibited, and a loft to host visiting artists. "It's still the polka dot," Guyton remarked to Lyman. "It's just got one of our presidents on it now." To help fund the project, Guyton auctioned off art from one of his Heidelberg Project buildings.

Guyton has learned to cooperate and collaborate with the government groups that once tried to destroy his work. As the artist told a contributor in the Detroit Free Press: "For a long time, I was mad because people didn't understand my work." "I couldn't let that go," he added. "They had to understand it. They had to appreciate it. I kept talking about the future, but I was being held back by the past." His new attitude has brought partnerships with government and civic groups, as well as corporate sponsorships. His success keeps growing. More than twenty years after he started the Heidelberg Project, it receives more than 275,000 visitors from around the world each year. The Project sponsors garden projects in the neighborhood and several educational programs for children. This is what his work is about, he told Martineau: "Tapping into new possibilities, transforming perceptions about life and art, building bridges and connecting with people."

In a statement on his official Web site, Guyton wrote: "I strive to be a part of the solution. I see and understand how order is needed in the world and in our individual lives. My experiences have granted me knowledge of how to create art and how to see beauty in everything that exists." He added: "For me, art is a way of expressing life. My work is a science that deals with colors, shapes, objects that brings about a rare beauty to the mind and eyes of people, a type of esthete. My art is life, life that lives on with time because the entire creation is an art form."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born August 24, 1955, in Detroit, MI; son of George and Betty Guyton; married Karen Smith, July 19, 1987 (divorced, 1994); married Jenenne Whitfield (an art agent and executive director), October 5, 2001; children: Tyree Jr., Towan, Omar, James, Tylisa. Addresses: Office: Heidelberg Project, 3360 Charlevoix, Detroit, MI 48207.