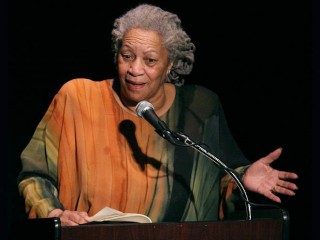

Toni Morisson biography

Date of birth : 1931-02-18

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Lorain, Ohio, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-12

Credited as : Author and writer, ,

0 votes so far

"Sidelights"

Nobel laureate Toni Morrison has a central role in the American literary canon, according to many critics, award committees, and readers. Her award-winning novels chronicle small-town African American life. Through works such as The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon, and Beloved, Morrison proves herself to be a gifted teller of stories in which troubled characters seek to find themselves and their cultural riches in a society that warps or impedes such essential growth. According to Charles Larson, writing in the Chicago Tribune Book World, each of Morrison's novels "is as original as anything that has appeared in our literature in the last twenty years. The contemporaneity that unites them--the troubling persistence of racism in America--is infused with an urgency that only a black writer can have about our society."

Morrison has also proved herself to be an able creator of children's books, working in collaboration with her son Slade Morrison. Together the two writers have produced the rhyming parable The Big Box and The Book of Mean People, narrated by a young rabbit and giving a child's eye view of the world. They have also collaborated on a series of retellings of the tales from Aesop, titled "Who's Got Game?"

Morrison's artistry has attracted critical acclaim as well as commercial success. Dictionary of Literary Biography contributor Susan L. Blake called the author "an anomaly in two respects ... she is a black writer who has achieved national prominence and popularity, and she is a popular writer who is taken seriously." Indeed, Morrison has won several of modern literature's most prestigious citations, including the 1977 National Book Critics Circle Award for Song of Solomon, the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Beloved, and the 1993 Nobel Prize for Literature, becoming the first African American to be named a laureate. Atlantic correspondent Wilfrid Sheed noted that "Most black writers are privy, like the rest of us, to bits and pieces of the secret, the dark side of their group experience, but Toni Morrison uniquely seems to have all the keys on her chain, like a house detective. ... She [uses] the run of the whole place, from ghetto to small town to ramshackle farmhouse, to bring back a panorama of black myth and reality that [dazzles] the senses."

Morrison was born Chloe Anthony Wofford in Lorain, Ohio, a small industrial town near the shores of Lake Erie. Two important aspects of Chloe Wofford's childhood--community spirit and the supernatural--inform Toni Morrison's mature writing.

On several levels, the pariah--a unique and sometimes eccentric individual--figures in Morrison's fictional reconstructions of African American community life. "There is always an elder there," she noted of her work in Black Women Writers (1950-1980): A Critical Evaluation. "And these ancestors are not just parents, they are sort of timeless people whose relationships to the characters are benevolent, instructive, and protective, and they provide a certain kind of wisdom." Sometimes this figure imparts his or her wisdom from beyond the grave; from an early age Morrison absorbed the folklore and beliefs of a culture for which the supernatural holds power and portent.

As a student, Morrison earned money by cleaning houses; "the normal teenage jobs were not available," she recalled in a New York Times Magazine profile by Claudia Dreifus. "Housework always was." Some of her clients were nice; some were "terrible," Morrison added. The work gave her a perspective on black-white relations that touched Morrison's later writing. As she told Dreifus, "In [The Bluest Eye ] Pauline lived in this dump and hated everything in it. And then she worked for the Fishers, who had this beautiful house, and she loved it. She got a lot of respect as their maid that she didn't get anywhere else." While never explicitly autobiographical, Morrison's fictions draw upon her youthful experiences in Ohio. In an essay for Black Women Writers at Work, she claimed that "I am from the Midwest so I have a special affection for it. My beginnings are always there. ... No matter what I write, I begin there. ... It's the matrix for me. ... Ohio also offers an escape from stereotyped black settings. It is neither plantation nor ghetto."

After graduating from high school with honors, Morrison attended Howard University, where she earned a degree in English. During this time, she also decided to change her first name to Toni. Morrison then earned a master's degree in English literature from Cornell University. During this period, Morrison met and married her husband, an architect with whom she had two sons. In 1955, Morrison became an English instructor at Texas Southern University. Two years later, she returned to Howard University, teaching English until 1964. It was during her stint at Howard that Morrison first began to write. When her marriage ended in 1964, Morrison moved to New York, where she supported herself and her sons by working as a book editor at Random House. Morrison held this position until 1985, during which time she influenced several prominent African American writers.

Morrison's own writing career took off in the late 1960s, and several themes and influences were in early evidence. Critics claim that Morrison strives to lay bare the injustice inherent in the African American condition and African Americans' efforts, individually and collectively, to transcend society's unjust boundaries. Blake noted that Morrison's novels explore "the difference between black humanity and white cultural values. This opposition produces the negative theme of the seduction and betrayal of black people by white culture ... and the positive theme of the quest for cultural identity."

The quest for self is a motivating and organizing device in Morrison's fiction, as is the role of family and community in nurturing or challenging the individual. According to Dorothy H. Lee in Black Women Writers (1950-1980), Morrison is preoccupied "with the effect of the community on the individual's achievement and retention of an integrated, acceptable self. In treating this subject, she draws recurrently on myth and legend for story pattern and characters, returning repeatedly to the theory of quest. ... The goals her characters seek to achieve are similar in their deepest implications, and yet the degree to which they attain them varies radically because each novel is cast in unique human terms." In Morrison's books, African Americans must confront the notion that all understanding is accompanied by pain, just as all comprehension of national history must include the humiliations of slavery.

Morrison is a pioneer in the depiction of the hurt inflicted by blacks on blacks; for instance, her characters rarely achieve harmonious relationships but are instead divided by futurelessness and the anguish of stifled existence.

Other critics detected a deeper undercurrent to Morrison's work that contains just the sort of epiphany for which she strives. Harvard Advocate essayist Faith Davis wrote that despite the mundane boundaries of Morrison's characters' lives, the author "illuminates the complexity of their attitudes toward life. Having reached a quiet and extensive understanding of their situation, they can endure life's calamities. ... Morrison never allows us to become indifferent to these people. ... Her citizens ... jump up from the pages vital and strong because she has made us care about the pain in their lives." In Ms., Margo Jefferson concluded that Morrison's books "are filled with loss--lost friendship, lost love, lost customs, lost possibilities. And yet there is so much life in the smallest acts and gestures ... that they are as much celebrations as elegies." Although Morrison does not like to be called a poetic writer, critics often comment on the lyrical quality of her prose.

In the mid-1960s, Morrison completed her first novel, The Bluest Eye. Although she had trouble getting the book into print--the manuscript was rejected several times--it was finally published in 1969. At age thirty-eight, Morrison was a published author, and her debut, set in Morrison's hometown of Lorain, Ohio, portrays "in poignant terms the tragic condition of blacks in a racist America," to quote Chikwenye Okonjo Ogunyemi in Critique. In The Bluest Eye, Morrison depicts the onset of African American self-hatred as occasioned by Caucasian American ideals such as "Dick and Jane" primers and Shirley Temple movies. The principal character, Pecola Breedlove, is literally maddened by the disparity between her existence and the pictures of beauty and gentility disseminated by the dominant white culture. As Phyllis R. Klotman noted in the Black American Literature Forum, Morrison "uses the contrast between Shirley Temple and Pecola ... to underscore the irony of black experience. Whether one learns acceptability from the formal educational experience or from cultural symbols, the effect is the same: self-hatred." Darwin T. Turner elaborated on the novel's intentions in Black Women Writers (1950-1980). Morrison's fictional milieu, wrote Turner, is "a world of grotesques--individuals whose psyches have been deformed by their efforts to assume false identities, their failures to achieve meaningful identities, or simply their inability to retain and communicate love."

Blake characterized The Bluest Eye as a novel of initiation, exploring that common theme in American literature from a minority viewpoint. Ogunyemi contended that, in essence, Morrison presents "old problems in a fresh language and with a fresh perspective. A central force of the work derives from her power to draw vignettes and her ability to portray emotions, seeing the world through the eyes of adolescent girls." Klotman, who called the book "a novel of growing up, of growing up young and black and female in America," concluded her review with the comment that the "rite of passage, initiating the young into womanhood at first tenuous and uncertain, is sensitively depicted. ... The Bluest Eye is an extraordinarily passionate yet gentle work, the language lyrical yet precise--it is a novel for all seasons."

The 1994 reissue of The Bluest Eye prompted a new set of appraisals. In an African American Review piece, Allen Alexander found that religious references--from both Western and African sources--"abound" in the novel's pages. "And of the many fascinating religious references," Alexander continued, "the most complex ... are her representations of and allusions to God. In Morrison's fictional world, God's characteristics are not limited to those represented by the traditional Western notion of the Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Ghost." Instead, Morrison presents God as having "a fourth face, one that is an explanation for all those things--the existence of evil, the suffering of the innocent and just--that seem so inexplicable in the face of a religious tradition that preaches the omnipotence of a benevolent God." Cat Moses used the forum of African American Review to contribute an essay outlining the blues aesthetic in The Bluest Eye. The narrative's structure, Moses wrote, "follows a pattern common to traditional blues lyrics: a movement from an initial emphasis on loss to a concluding suggestion of resolution of grief through motion." In depicting the transition from loss to "movin' on," said the essayist, The Bluest Eye "contains an abundance of cultural wisdom."

In 1973's Sula, Morrison once again presents a pair of African American women who must come to terms with their lives. Set in a Midwestern African American community called the Bottom, the story follows two friends, Sula and Nel, from childhood to old age and death. Sula is a tale of rebellion and conformity in which the conformity is dictated by the solid inhabitants of the Bottom, and the rebellion gains strength from the community's disapproval. New York Times Book Review contributor Sara Blackburn contended, however, that the book is "too vital and rich" to be consigned to the category of allegory. Morrison's "extravagantly beautiful, doomed characters are locked in a world where hope for the future is a foreign commodity, yet they are enormously, achingly alive," wrote Blackburn. "And this book about them--and about how their beauty is drained back and frozen--is a howl of love and rage, playful and funny as well as hard and bitter." In the words of American Literature essayist Jane S. Bakerman, Morrison "uses the maturation story of Sula and Nel as the core of a host of other stories, but it is the chief unification device for the novel and achieves its own unity, again, through the clever manipulation of the themes of sex, race, and love. Morrison has undertaken a ... difficult task in Sula. Unquestionably, she has succeeded."

Other critics have echoed Bakerman's sentiments about Sula. Turner claimed that, in Sula, "Morrison evokes her verbal magic occasionally by lyric descriptions that carry the reader deep into the soul of the character. ... Equally effective, however, is her art of narrating action in a lean prose that uses adjectives cautiously while creating memorable vivid images." In her review, Faith Davis concluded in the Harvard Advocate that a "beautiful and haunting atmosphere emerges out of the wreck of these folks' lives, a quality that is absolutely convincing and absolutely precise." Sula was nominated for a National Book Award in 1974.

From the insular lives she depicted in her first two novels, Morrison moved in Song of Solomon to a national and historical perspective of African American life. "Here the depths of the younger work are still evident," wrote Reynolds Price in the New York Times Book Review, "but now they thrust outward, into wider fields, for longer intervals, encompassing many more lives. The result is a long prose tale that surveys nearly a century of American history as it impinges upon a single family." With a mixture of fantasy and the realism, Song of Solomon relates the journey of a character named Milkman Dead into an understanding of his family heritage and, hence, himself. Lee wrote in Black Women Writers (1950-1980), "Figuratively, [Milkman] travels from innocence to awareness, i.e., from ignorance of origins, heritage, identity, and communal responsibility to knowledge and acceptance. He moves from selfish and materialistic dilettantism to an understanding of brotherhood. With his release of personal ego, he is able to find a place in the whole. There is, then, a universal--indeed mythic--pattern here. He journeys from spiritual death to rebirth, a direction symbolized by his discovery of the secret power of flight. Mythically, liberation and transcendence follow the discovery of self." Blake suggested that the connection Milkman discovers with his family's past helps him to connect meaningfully with his contemporaries; Song of Solomon, Blake noted, "dramatizes dialectical approaches to the challenges of black life." According to Anne Z. Mickelson in Reaching Out: Sensitivity and Order in Recent American Fiction by Women, history itself "becomes a choral symphony to Milkman, in which each individual voice has a chance to speak and contribute to his growing sense of well-being."

Mickelson also observed that Song of Solomon represents for African Americans "a break out of the confining life into the realm of possibility." Larson commented on this theme in a Washington Post Book World review. The novel's subject matter, Larson explained, is "the origins of black consciousness in America, and the individual's relationship to that heritage." However, Larson added, "skilled writer that she is, Morrison has transcended this theme so that the reader rarely feels that this is simply another novel about ethnic identity. So marvelously orchestrated is Morrison's narrative that it not only excels on all of its respective levels, not only works for all of its interlocking components, but also--in the end--says something about life (and death) for all of us. Milkman's epic journey ... is a profound examination of the individual's understanding of, and, perhaps, even transcendence of the inevitable fate of his life."

Song of Solomon, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977, was also the first novel by an African American writer to become a Book-of-the-Month Club selection since Richard Wright's Native Son was published in 1940. World Literature Today reviewer Richard K. Barksdale called the work "a book that will not only withstand the test of time but endure a second and third reading by those conscientious readers who love a well-wrought piece of fiction." Describing the novel as "a stunningly beautiful book" in her Washington Post Book World piece, Anne Tyler added, "I would call the book poetry, but that would seem to be denying its considerable power as a story. Whatever name you give it, it's full of magnificent people, each of them complex and multilayered, even the narrowest of them narrow in extravagant ways." Price deemed Song of Solomon "a long story, ... and better than good. Toni Morrison has earned attention and praise. Few Americans know, and can say, more than she has in this wise and spacious novel."

Morrison clearly attained the respect of the literary community, but even in the face of three well-received novels, she did not call herself a writer. "I think, at bottom, I simply was not prepared to do the adult thing, which in those days would be associated with the male thing, which was to say, 'I'm a writer,'" she told Dreifus in 1994. "I said, 'I am a mother who writes,' or 'I am an editor who writes.' The word 'writer' was hard for me to say because that's what you put on your income-tax form. I do now say, 'I'm a writer.' But it's the difference between identifying one's work and being the person who does the work. I've always been the latter."

Still, critics and readers had no doubt that Morrison was a writer. Her 1981 book Tar Baby remained on best seller lists for four months. A novel of ideas, the work dramatizes the fact that complexion is a far more subtle issue than the simple polarization of black and white. Set on a lush Caribbean island, Tar Baby explores the passionate love affair of Jadine, a Sorbonne-educated black model, and Son, a handsome knockabout with a strong aversion to white culture. In a Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook essay, Elizabeth B. House outlined Tar Baby's major themes: "the difficulty of settling conflicting claims between one's past and present and the destruction which abuse of power can bring. As Morrison examines these problems in Tar Baby, she suggests no easy way to understand what one's link to a heritage should be, nor does she offer infallible methods for dealing with power. Rather, with an astonishing insight and grace, she demonstrates the pervasiveness of such dilemmas and the degree to which they affect human beings, both black and white."

Tar Baby uncovers racial and sexual conflicts without offering solutions, but most critics found that Morrison indicts all of her characters--black and white--for their thoughtless devaluations of others. In the New York Times Book Review, John Irving claimed that "What's so powerful, and subtle, about Miss Morrison's presentation of the tension between blacks and whites is that she conveys it almost entirely through the suspicions and prejudices of her black characters. ... Miss Morrison uncovers all the stereotypical racial fears felt by whites and blacks alike. Like any ambitious writer, she's unafraid to employ these stereotypes--she embraces the representative qualities of her characters without embarrassment, then proceeds to make them individuals too."

Reviewers praised Tar Baby for its provocative themes and for its evocative narration. Los Angeles Times contributor Elaine Kendall called the book "an intricate and sophisticated novel, moving from a realistic and orderly beginning to a mystical and ambiguous end. Morrison has taken classically simple story elements and realigned them so artfully that we perceive the old pattern in a startlingly different way. Although this territory has been explored by dozens of novelists, Morrison depicts it with such vitality that it seems newly discovered." In the Washington Post Book World, Webster Schott claimed that "There is so much that is good, sometimes dazzling, about Tar Baby --poetic language, ... arresting images, fierce intelligence--that ... one becomes entranced by Toni Morrison's story. The settings are so vivid the characters must be alive. The emotions they feel are so intense they must be real people." Maureen Howard stated in New Republic that the work "is as carefully patterned as a well-written poem. ... Tar Baby is a good American novel in which we can discern a new lightness and brilliance in Toni Morrison's enchantment with language and in her curiously polyphonic stories that echo life." Schott concluded, "One of fiction's pleasures is to have your mind scratched and your intellectual habits challenged. While Tar Baby has shortcomings, lack of provocation isn't one of them. Morrison owns a powerful intelligence. It's run by courage. She calls to account conventional wisdom and accepted attitude at nearly every turn."

In addition to her own writing, Morrison during this period helped to publish the work of other noted African Americans, including Toni Cade Bambara, Gayle Jones, Angela Davis, and Muhammad Ali. Discussing her aims as an editor in a quotation printed in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, Morrison said, "I look very hard for black fiction because I want to participate in developing a canon of black work. We've had the first rush of black entertainment, where blacks were writing for whites, and whites were encouraging this kind of self-flagellation. Now we can get down to the craft of writing, where black people are talking to black people."

One of Morrison's important projects for Random House was The Black Book, an anthology of items that illustrate the history of African Americans. Ms. magazine correspondent Dorothy Eugenia Robinson described the work: "The Black Book is the pain and pride of rediscovering the collective black experience. It is finding the essence of ourselves and holding on. The Black Book is a kind of scrapbook of patiently assembled samplings of black history and culture. What has evolved is a pictorial folk journey of black people, places, events, handcrafts, inventions, songs, and folklore. ... The Black Book informs, disturbs, maybe even shocks. It unsettles complacency and demands confrontation with raw reality. It is by no means an easy book to experience, but it's a necessary one."

While preparing The Black Book for publication, Morrison uncovered the true and shocking story of a runaway slave who, at the point of recapture, murdered her infant child so it would not be doomed to a lifetime of servitude. For Morrison, the story encapsulated the fierce psychic cruelty of an institutionalized system that sought to destroy the basic emotional bonds between men and women, and worse, between parent and child. "I certainly thought I knew as much about slavery as anybody," Morrison told an interviewer for the Los Angeles Times. "But it was the interior life I needed to find out about." It is this "interior life" in the throes of slavery that constitutes the theme of Morrison's novel Beloved. Set in Reconstruction-era Cincinnati, the book centers on characters who struggle fruitlessly to keep their painful recollections of the past at bay. They are haunted, both physically and spiritually, by the legacies slavery has bequeathed to them.

While the book was not unanimously praised--New Republic writer Stanley Crouch cited the author for "almost always [losing] control" and of not resisting "the temptation of the trite or the sentimental"--many critics considered Beloved to be Morrison's masterpiece. In People, V.R. Peterson described the novel as "a brutally powerful, mesmerizing story about the inescapable, excruciating legacy of slavery. Behind each new event and each new character lies another event and another story until finally the reader meets a community of proud, daring people, inextricably bound by culture and experience." Through the lives of ex-slaves Sethe and her would-be lover Paul D, readers "experience American slavery as it was lived by those who were its objects of exchange, both at its best--which wasn't very good--and at its worst, which was as bad as can be imagined," wrote Margaret Atwood in the New York Times Book Review. "Above all, it is seen as one of the most viciously antifamily institutions human beings have ever devised. The slaves are motherless, fatherless, deprived of their mates, their children, their kin. It is a world in which people suddenly vanish and are never seen again, not through accident or covert operation or terrorism, but as a matter of everyday legal policy." New York Times columnist Michiko Kakutani contended that Beloved "possesses the heightened power and resonance of myth--its characters, like those in opera or Greek drama, seem larger than life and their actions, too, tend to strike us as enactments of ancient rituals and passions. To describe Beloved only in these terms, however, is to diminish its immediacy, for the novel also remains precisely grounded in American reality--the reality of Black history as experienced in the wake of the Civil War."

Beloved may be an American novel, but its images and influences come from the British romantic tradition, theorized Martin Bidney in Papers on Language and Literature. "Simply to list a few of [the book's] major episodes--ice skating, boat stealing, gigantic shadow, carnival 'freak' show, water-voices sounding the depths--is almost to create a rapidly scrolled plot synopsis of Wordsworth's Prelude," Bidney wrote. "When Baby Suggs declares that the only grace we will receive is the grace we can 'imagine,' or when Sethe tells how Paul D's visionary capacity makes 'windows' suddenly have 'view,' we hear the voice of William Blake." The critic also saw traces of the poet John Keats in the scenes of Paul D's musings "on the superiority of imagined love to mere physical sex." But the achievement of the novel ultimately belongs to Morrison, Bidney added: "These few examples are by no means a complete listing of all the Romantic allusive motifs that combined to help make Beloved the visionary masterwork it is."

In his Chicago Tribune piece, Larson claimed that the work "is the context out of which all of Morrison's earlier novels were written. In her darkest and most probing novel, Toni Morrison has demonstrated once again the stunning powers that place her in the first ranks of our living novelists." Los Angeles Times Book Review contributor John Leonard likewise expressed the opinion that the novel "belongs on the highest shelf of American literature, even if half a dozen canonized white boys have to be elbowed off. ... Without Beloved our imagination of the nation's self has a hole in it big enough to die from." Atwood wrote, "Ms. Morrison's versatility and technical and emotional range appear to know no bounds. If there were any doubts about her stature as a pre-eminent American novelist, of her own or any other generation, Beloved will put them to rest." London Times reviewer Nicholas Shakespeare concluded that Beloved "is a novel propelled by the cadences of ... songs--the first singing of a people hardened by their suffering, people who have been hanged and whipped and mortgaged at the hands of white people--the men without skin. From Toni Morrison's pen it is a sound that breaks the back of words, making Beloved a great novel."

But for all its acclaim, Beloved became the object of controversy when the novel failed to win either the 1987 National Book Award or the National Book Critics Circle Award. In response, forty-eight prominent African American authors--including Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, and John Wideman--signed a letter to the editor that appeared in the New York Times on January 24, 1988. The letter expressed the signers' dismay at the "oversight and harmful whimsy" that resulted in the lack of recognition for Beloved. The "legitimate need for our own critical voice in relation to our own literature can no longer be denied," declared Morrison's peers. The authors concluded their letter with a tribute to Morrison: "For all of America, for all of American letters, you have advanced the moral and artistic standards by which we must measure the daring and the love of our national imagination and our collective intelligence as a people." The letter sparked fierce debate within the New York literary community, "with some critics accusing the authors of the letter of racist manipulation," according to an entry in Newsmakers: 1998 Cumulation. Beloved ended up winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1988.

Morrison's subsequent novel, Jazz, is "a fictive re-creation of two parallel narratives set during major historical events in African American history--Reconstruction and the Jazz Age," noted Dictionary of Literary Biography writer Denise Heinze. Set primarily in New York City during the 1920s, the novel's main narrative involves a love triangle between Violet, a middle-aged woman; Joe, her husband; and Dorcas, Joe's teenage mistress. When Dorcas snubs Joe for a younger lover, Joe shoots and kills Dorcas. Violet seeks to understand the dead girl by befriending Dorcas's aunt, Alice Manfred. Simultaneously, Morrison relates the story of Joe and Violet's parents and grandparents. In telling these stories, Morrison touches on a number of themes: "male/female passion," as Heinze commented; the movement of African Americans into large urban areas after Reconstruction; and, as is usually the case with her novels, the effects of racism and history on the African American community. Morrison also makes use of an unusual storytelling device: an unnamed, intrusive, and unreliable narrator.

"The standard set by the brilliance and intensity of Morrison's previous novel Beloved is so high that Jazz does not pretend to come close to attaining it," stated Kenyon Review contributor Peter Erickson. Nevertheless, many reviewers responded enthusiastically to the provocative themes Morrison presents in Jazz. "The unrelenting, destructive influence of racism and oppression on the black family is manifested in Jazz by the almost-total absence of the black family," stated Heinze. Writing in the New York Review of Books, Michael Wood remarked that "black women in Jazz are arming themselves, physically and mentally, and in this they have caught a current of the times, a not always visible indignation that says enough is enough." Several reviewers felt that Morrison's use of an unreliable narrator impeded the story's effectiveness. Erickson, for instance, averred that the narrator "is not inventive enough. Because the narrator displays a lack of imagination at crucial moments, she seems to get in the way, to block rather than to enable access to deeper levels." Heinze, on the other hand, found that Morrison's unreliable narrator allows the author to engage the reader in a way that she has not done in her previous novels: "In Jazz Morrison questions her ability to answer the very issues she raises, extending the responsibility of her own novel writing to her readers." Heinze concluded, "Morrison thereby sends an invitation to her readers to become a part of that struggle to comprehend totality that will continue to spur her genius."

Morrison's "genius" was recognized a year after the publication of Jazz with a momentous award: the Nobel Prize for Literature. The first black and only the eighth woman to win the award, Morrison told Dreifus that "it was as if the whole category of 'female writer' and 'black writer' had been redeemed. I felt I represented a whole world of women who either were silenced or who had never received the imprimatur of the established literary world." In describing the author after its selection, the Nobel Committee noted, as quoted by Heinze: "She delves into the language itself, a language she wants to liberate from the fetters of race. And she addresses us with the luster of poetry." In 1996, Morrison received another prestigious award, the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters; this was followed by the National Humanities Medal in 2001.

In Paradise, Morrison's first novel after winning the Nobel Prize, noted America contributor Hermine Pinson, "the writer appears to be reinterpreting some of her most familiar themes: the significance of the 'ancestor' in our lives, the importance of community, the concept of 'home,' and the continuing conundrum of race in the United States. The title and intended subject of the text--Paradise--accommodates all of the foregoing themes." Like Beloved, Paradise "centers on a catastrophic act of violence that begs to be understood," National Catholic Reporter contributor Judith Bromberg explained. "Morrison meticulously peels away layer upon layer of truth so that what we think we know, we don't until she finally confronts us with raw truth." The conflict, and the violence that results from it, comes out of the dedicated self-righteousness of the leading families of a small town. "The story begins in Oklahoma in 1976," Pinson wrote, "when nine men from the still all-black town of Ruby invade the local convent on a mission to keep the town safe from the outright evil and depravity that they believe is embodied in the disparate assembly of religious women who live there." "In a show of force a posse of nine descend on the crumbling mansion in the predawn of a summer morning, killing all four of the troubled, flawed women who have sought refuge there," Bromberg stated.

Many reviewers recognized Morrison's accomplishment in Paradise. John Kennedy in Antioch Review called Morrison's opening chapter "Faulknerian;" with its "rich, evocative and descriptive passages, it is a haunting introduction to the repressed individuality that stalks 'so clean and blessed a mission.'" The novel "is full of challenges and surprises," wrote Christian Century reviewer Reggie Young. "Though it does not quite come up to the standard of Morrison's masterwork, Beloved, this is one of the most important novels of the decade." "This is Morrison's first novel since her 1993 Jazz," noted Emily J. Jones in Library Journal, "and it is well worth the wait."

In addition to her novels, Morrison has also published in other genres. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination is a collection of three lectures that Morrison gave at Harvard University in 1990. Focusing on racism as it has manifested itself in American literature, these essays of literary criticism explore the works of authors such as Willa Cather, Mark Twain, and Ernest Hemingway. In 1992, Morrison edited Race-ing Justice, En-gendering Power: Essays on Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas, and the Construction of Social Reality, eighteen essays about Thomas's nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Turning her attention to younger readers, Morrison collaborated with her son Slade on a 1999 picture book called The Big Box, based on a story Slade made up when he was nine. Morrison provided the verse for a tale of three children living in "a big brown box [with] three big locks." The children have been sent there by their parents, who feel the high-spirited and imaginative youngsters "can't handle their freedom." These children have all done something to upset the parents: Patty is too talkative in the library; Liza Sue allows the chickens to keep their eggs; and Mickey plays when he should not. The adults do not like rebellious children and so put them away, not even bothering to listen to their repeated protest: "I know that you think / You're doing what is best for me. / But if freedom is handled just your way / Then it's not my freedom or free."

While the tale ends happily, the generally downbeat tone of the story made some critics wary of the children's book. A contributor for Publishers Weekly faulted the picture book for having "little of the childlike perspective that so masterfully informs The Bluest Eye." A Horn Book contributor likewise complained of the "heavy-handed irony" that informs much of the book. Hazel Rochman, writing in Booklist, decided that The Big Box "will appeal most to adults who cherish images of childhood innocence in a fallen world." Ellen Fader, writing in School Library Journal, felt the book "will have a hard time finding its audience," as it appears to be for children, but the message "requires more sophistication." A critic for Kirkus Reviews, however, noted that the message of the book is "valid" and "strongly made," calling the work "a promising children's book debut." And a reviewer for Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy also had praise for the title, remarking favorably upon the "haunting message about children who don't fit the accepted definitions of ... 'normal.'"

Teaming up again with her son Slade, Morrison published another juvenile title in 2002, The Book of Mean People, a "bittersweet volume [that] takes meanness in stride and advocates kindness as the antidote," observed a contributor for Publishers Weekly. The narrative is a catalog of the things adults do to kids that kids often interpret as being mean. Grownups shout when something is wrong, make children eat things they do not like, and even dictate the time youngsters are to be in bed. These thoughts seemingly come from a bunny featured in the illustrations by Pascal Lemaître.

Overall, this second children's title enjoyed a more positive critical reception than the first. A Kirkus Reviews critic thought that young readers "who know just what the young narrator is talking about may take to heart the closing advice to smile in the face of frowns." School Library Journal contributor Judith Constantinides felt that "the book could be used as a springboard to discuss anger and shouting." Evette Porter, writing in Black Issues Book Review, found The Book of Mean People "a witty yet candid look at anger from the perspective of a child." The book was published in tandem with an interactive journal so that children can record their responses to situations that make them feel angry and helpless. A contributor writing in Publishers Weekly thought that the questions supplied as writing prompts in the journal "encourage reflection," while Porter commented that the journal could "serve as a preschool primer in anger-management therapy."

In 2003, Morrison published the novel Love. The story centers on the Cosey Hotel and Resort, a popular place for African Americans to vacation in the 1940s and 1950s. Twenty-five years after the death of the charismatic owner of the resort, a well-off African American man named Bill Cosey, the women named in his will discuss their thoughts about him and the impact he has had on their lives. The novel incorporates elements of bias based on financial status and the strife that money can cause between loved ones. World Literature Today contributor Daniel Garrett commented that the book, "which is richer and wilder than most books, reminds me of other entertainments, both within and outside Morrison's oeuvre--and that makes it a surprising disappointment." Nola Theiss offered a different assessment in a Kliatt review, stating that the "language requires careful reading as each sentence is a poem in itself." Theiss concluded that Love, "raw and ethereal at the same time, ... will be read for generations."

Barbara Lipkien Gershenbaum, writing for the Bookreporter.com Web site, asserted that Morrison "is soft-spoken, gracious, charming, down-to-earth, curious about her readers, and patiently answers questions. On the continuum of her work, Love is the next logical leap in her immutable search for the answers to the questions of life that interest her." Also writing for the Bookreporter.com Web site, Stephen M. Deusner mentioned that certain "missteps reveal just how forcefully Morrison is straining to make Love work, to stretch a threadbare family saga to cover such large ideas about race and gender. That she does make it work at all, that her insights more often than not hit their targets, and that Love is readable and fascinating seem like an extreme act of will, and there is a certain purity in such literary labor." Nicole Moses, in a review for January, opined that, "in all, Love is a beautifully executed piece of work, even down to its red-wine colored cover and elegant gold lettering. It finishes on a powerful and surprising note, reminding me of Morrison's distinct talent for hiding clues in plain sight and keeping key facts under wraps until the last minute. This is the second novel of hers that she describes as 'perfect' (the first is Jazz), and with it, Morrison adds yet another brilliant classic to her collection."

Elaine Showalter, reviewing the novel in the London Guardian, found that "Morrison's imaginative range of identification is narrower by choice; although she would no doubt argue--and rightly--that African American characters can speak for all humanity. But in Love, they do not; they are stubbornly bound by their own culture; and thus, while Love is certainly an accomplished novel, its perfection comes from its limitation." Booklist contributor Brad Hooper claimed that, "as a vivid painter of human emotions, Morrison is without peer, her impressions rendered in an exquisitely metaphoric but comfortably open style."

Morrison published the novel A Mercy in 2008. Set in the American colonies in the 1600s, a time when the slave trade flourished, the novel introduces Florens, who was offered as debt payment by a slave to a northern farmer. Everyone on the plantation has his or her own view of this act, and they share their stories throughout the novel.

A contributor writing on the Center for Public Christianity Web site commented that "those familiar with Morrison will know that she is peerless in writing about human suffering with piercing, devastating elegance. Her stories are frequently embedded in the experience of black Americans and their encounter with fear, mistrust and hatred." The same contributor also found that a "longing for wholeness is a driving force of Morrison's writing. All around is brokenness and fragility. Even the most admirable characters are full of flaws. The church--the place that should offer restoration and a healing balm--comes in for some rough treatment. It is clear the author knows all too well what occurs when the devoted fail to reflect their gospel roots." Booklist contributor Hooper stated that A Mercy is "a fitting companion to her highly regarded Beloved. "

Caroline Moore, writing in the London Telegraph, commented that "the symbolism might seem simple; the human ramifications are not. Emotions run deep and twisted in Morrison's fiction; and their outcome is superbly traced in this powerful, flawed and genuinely creative novel." Tim Adams, reviewing the novel in the London Observer, observed that "Morrison structures the novel in her familiar manner, giving one chapter by turns to each competing voice, collapsing time frames, seldom letting her characters directly rub up against one another, trapping each of them in their biographies. In this way, she creates something that lives powerfully as an invented oral history and that seems to demand to be taken as a parable, but one whose meaning--which lives in the territory of harshness and sacrifice--is constantly undermined or elusive."

A contributor to the Fresh Ink Books Web log remarked that "this is not a fast read for most, the story should be read slowly, the language is rich, almost dense at times, and needs to be savoured. But what a powerful story it is." In a review for the London Independent, Emma Hagestadt noted that, in A Mercy, "the story of America's messy birth lies in its terms of enslavement." Mary Whipple, reviewing the novel for Mostly Fiction, stated that, "An intense and thought-provoking look at slavery from its beginnings, this is a novel of epic scope, filled with complex philosophical, Biblical, and feminist issues and symbols. Morrison's themes are clear and unambiguous, and her many admirers will celebrate this novel for its message, even as they may regret its sacrifice of full character development to that message."

In 2008 Morrison published What Moves at the Margin: Selected Nonfiction, which was edited and introduced by Carolyn C. Denard. This collection of Morrison's essays covers three decades and covers topics ranging from the author's definition of what it means to be a black woman to the art of writing. Booklist contributor Donna Seaman described the author as being "a master stylist, penetrating thinker, and committed artist wholly engaged in transforming lives." A contributor writing in Publishers Weekly claimed that "Denard's judicious selections offer eloquent insights into the themes that are the rich ground for Morrison's haunting fiction." Erin E. Dorney, reviewing the book in Library Journal, said that the book "is an important resource for aspiring writers, Morrison fans, and any African American studies program." Sathyaraj Venkatesan, reviewing the book in Melus, mentioned that "although What Moves at the Margin will be appreciated by a variety of audiences, some of Morrison significant statements, such as 'City Limits and Village Values: The Concept of Neighborhood in Black Fiction,' 'Memory, Creation, and Writing,' and 'Home,' are conspicuously absent." "That said," conceded Venkatesan, " What Moves at the Margin is the first substantial collection of essays that brings to the fore Morrison's social command, moral vision, and aesthetic Weltanschauung--a worldview that helps us interpret the complex realities confronting American and African American cultural politics. The collection also urges literary critics to reread Morrison's fiction alongside her nonfiction."

Morrison and her son published Peeny Butter Fudge, illustrated by Joe Cepeda, the following year. Mom drops off her three kids and grandma's house with a list of instructions. Instead, grandma decides to treat the kids to sack races, playing doctor, and making a batch of her famous peeny butter fudge. Although mom is mad they did not follow the list, she quickly forgets as the fudge reminds her of her own childhood. Meg Smith, writing in School Library Journal, remarked that "the illustrations extend the narrative, adding humor and warmth to this offering." A contributor writing in Kirkus Reviews described the account as being "a fast-paced read-aloud that celebrates intergenerational love with a mixing-bowl-ful of humor." A contributor writing in Publishers Weekly remarked that "this is a vision of family life that many kids ... will regard with envy." Booklist contributor Daniel Kraus observed that "the couplets are conversational, though occasionally they barely rhyme." Nevertheless, Kraus called Cepeda's illustrations "a perfect mix of earthy and boisterous."

Little Cloud and Lady Wind, published in 2010, was coauthored by Morrison and her son and illustrated by Sean Qualls. Little Cloud distances herself from the group mentality of her peers when they decide to terrorize the Earth with their thunder and storms. She is carried to a beautiful valley by Lady Wind, where she is able to be herself.

A contributor writing in Publishers Weekly thought that "the text sometimes feels heavy-handed," adding that "the conclusion, in contrast to the story's espousal of freedom, seems preordained." C.J. Connor, reviewing the book in School Library Journal, believed that "young readers will empathize with Little Cloud." However, Connor opined that "the oft-told story is tired, and even Qualls's whimsical depictions ... can't freshen it." A contributor writing in Kirkus Reviews noted that aside from its "'60s love-in mentality, the story seems to be an homage to Aeolian spirits that reworks the Aesop fable." Booklist contributor Andrew Medlar called the story "poetic" and "gentle," adding that Little Cloud and Lady Wind "will resonate with anyone who has been caught in the tempest of mean or unfriendly behavior."

In an interview in Time, Morrison shared her views and advice for aspiring writers. She stated that "the work is in the work itself. If she writes a lot, that's good. If she revises a lot, that's even better. She should not only write about what she knows but about what she doesn't know. It extends the imagination."

Whether she is pigeonholed as a black woman writer or thought of as simply an American novelist, Morrison is a prominent and respected figure in modern letters. As testament to her influence, something of a cottage industry has arisen of Morrison assessments. Several books and dozens of critical essays are devoted to the examination of her fiction. Though popular acceptance of her work has seldom flagged, Morrison found Song of Solomon shooting to the best seller lists again after being selected by talk-show host Oprah Winfrey as a book-club pick in 1996; in 2002, Sula was the novel chosen to close out Winfrey's popular discussion group. The author's hometown of Lorain, Ohio, is the setting for the biennial Toni Morrison Society Conference; a 2000 gathering attracted 130 scholars from around the globe.

House commended Morrison for the universal nature of her work. "Unquestionably," House wrote, "Toni Morrison is an important novelist who continues to develop her talent. Part of her appeal, of course, lies in her extraordinary ability to create beautiful language and striking characters. However, Morrison's most important gift, the one which gives her a major author's universality, is the insight with which she writes of problems all humans face. ... At the core of all her novels is a penetrating view of the unyielding, heartbreaking dilemmas which torment people of all races." In Black Women Writers (1950-1980), Lee concluded of Morrison's accomplishments: "Though there are unifying aspects in her novels, there is not a dully repetitive sameness. Each casts the problems in specific, imaginative terms, and the exquisite, poetic language awakens our senses as she communicates an often ironic vision with moving imagery. Each novel reveals the acuity of her perception of psychological motivation of the female especially, of the Black particularly, and of the human generally."

"The problem I face as a writer is to make my stories mean something," Morrison stated in an interview in Black Women Writers at Work. "You can have wonderful, interesting people, a fascinating story, but it's not about anything. It has no real substance. I want my books to always be about something that is important to me, and the subjects that are important in the world are the same ones that have always been important." In Black Women Writers (1950-1980), she elaborated on this idea. Fiction, she wrote, "should be beautiful, and powerful, but it should also work. It should have something in it that enlightens; something in it that opens the door and points the way. Something in it that suggests what the conflicts are, what the problems are. But it need not solve those problems because it is not a case study, it is not a recipe."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born Chloe Anthony Wofford, February 18, 1931, in Lorain, OH; daughter of George and Ramah Wofford; married Harold Morrison, 1958 (divorced, 1964); children: Harold Ford, Slade Kevin. Education: Howard University, B.A., 1953; Cornell University, M.A., 1955. Memberships: American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, National Council on the Arts, Authors Guild (council), Authors' League of America.

AWARDS

National Book Award nomination and Ohioana Book Award, both 1975, both for Sula; National Book Critics Circle Award and American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters Award, both 1977, both for Song of Solomon; New York State Governor's Art Award, 1986; National Book Award nomination and National Book Critics Circle Award nomination, both 1987, Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, Robert F. Kennedy Award, and American Book Award, Before Columbus Foundation, 1988, all for Beloved; Elizabeth Cady Stanton Award, National Organization of Women; Nobel Prize in Literature, 1993; Pearl Buck Award, Rhegium Julii Prize, Condorcet Medal (Paris, France), and Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (Paris, France), all 1994; Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, National Book Foundation, 1996; National Humanities Medal, 2001; subject of Biennial Toni Morrison Society conference in Lorain, Ohio; Coretta Scott King Book Award, 2005, for Remember: The Journey to School Integration; honorary doctorate, Oxford University, 2005.

CAREER

Academic and writer. Texas Southern University, Houston, TX, instructor in English, 1955-57; Howard University, Washington, DC, instructor in English, 1957-64; Random House, New York, NY, senior editor, 1965-85; Purchase College, State University of New York, Purchase, associate professor of English, 1971-72; University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, Schweitzer Professor of the Humanities, 1984-89; Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, Robert F. Goheen Professor of the Humanities, 1989--. Visiting lecturer, Yale University, 1976-77, and Bard College, 1986-88; Clark Lecturer at Trinity College, Cambridge, and Massey Lecturer at Harvard University, both 1990.

WRITINGS:

NOVELS

* The Bluest Eye, Holt (New York, NY), 1969, reprinted, Plume (New York, NY), 1994, adapted as a play by Lydia R. Diamond, Dramatic (Woodstock, IL), 2007.

* Sula, Knopf (New York, NY), 1973.

* Song of Solomon, Knopf (New York, NY), 1977.

* Tar Baby, Knopf (New York, NY), 1981.

* Beloved, Knopf (New York, NY), 1987, with an introduction by A.S. Byatt, 2006.

* Jazz, Knopf (New York, NY), 1992.

* Paradise, Knopf (New York, NY), 1998.

* Love, Knopf (New York, NY), 2003.

* A Mercy, Knopf (New York, NY), 2008.

NONFICTION

* Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, Harvard University Press (Cambridge, MA), 1992.

* To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton, Writers and Readers (New York, NY), 1995.

* The Dancing Mind (text of Nobel Prize acceptance speech), Knopf (New York, NY), 1996.

* (With Claudia Brodsky Lacour) Birth of a Nation'hood: Gaze, Script, and Spectacle in the O.J. Simpson Case, Pantheon (New York, NY), 1997.

* Memoirs, Chatto & Windus (London, England), 1999.

* Remember: The Journey to School Integration (for children), Houghton Mifflin (Boston, MA), 2004.

* Toni Morrison: Conversations, edited by Carolyn C. Denard, University Press of Mississippi (Jackson, MS), 2008.

* What Moves at the Margin: Selected Nonfiction, edited and with an introduction by Carolyn C. Denard, University Press of Mississippi (Jackson, MS), 2008.

FOR CHILDREN; WITH SON, SLADE MORRISON

* The Big Box, illustrated by Giselle Potter, Hyperion/Jump at the Sun (New York, NY), 1999.

* The Book of Mean People, illustrated by Pascal Lemaître, Hyperion (New York, NY), 2002.

* The Book of Mean People Journal, illustrated by Pascal Lemaître, Hyperion (New York, NY), 2002.

* The Mirror or the Glass?, Scribner (New York, NY), 2007.

* Peeny Butter Fudge, illustrated by Joe Cepeda, Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (New York, NY), 2009.

* Little Cloud and Lady Wind, illustrated by Sean Qualls, Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (New York, NY), 2010.

* The Tortoise or the Hare, illustrated by Joe Cepeda, Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (New York, NY), 2010.

"WHO'S GOT GAME?" SERIES FOR CHILDREN; WITH SLADE MORRISON; ILLUSTRATED BY PASCAL LEMAÎTRE

* The Lion or the Mouse? (also see below), Scribner (New York, NY), 2003.

* The Ant or the Grasshopper? (also see below), Scribner (New York, NY), 2003.

* The Poppy or the Snake? (also see below), Scribner (New York, NY), 2004.

* Who's Got Game? Three Fables (contains The Lion or the Mouse?, The Ant or the Grasshopper?, and The Poppy or the Snake), Scribner (New York, NY), 2005.

MUSIC; AUTHOR OF LYRICS

* André Previn, Four Songs for Soprano, Cello, and Piano, Chester Music (London, England), 1995.

* Richard Danielpour, Spirits in the Well: For Voice and Piano, Associated Music Publishers (New York, NY), 1998.

* Richard Danielpour, Margaret Garner: Opera in Two Acts, Associated Music Publishers (New York, NY), 2005.

EDITOR

* The Black Book (anthology), Random House (New York, NY), 1974, with new foreword, 2009.

* Race-ing Justice, En-gendering Power: Essays on Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas, and the Construction of Social Reality, Pantheon (New York, NY), 1992.

* Toni Cade Bambara, Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions: Fiction, Essays, and Conversations, Pantheon (New York, NY), 1996.

* Huey P. Newton, To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton, City Lights Books (San Francisco, CA), 2009.

OTHER

* Dreaming Emmett (play), first produced in Albany, NY, January 4, 1986.

Also author of lyrics for André Previn's Honey and Rue, commissioned by Carnegie Hall, 1992, and Richard Danielpour's Sweet Talk: Four Songs, 1996.

Contributor of essays and reviews to numerous periodicals, including New York Times Magazine. Contributor to Arguing Immigration: The Debate over the Changing Face of America, edited by Nicolaus Mills, Simon & Schuster (New York, NY), 1994.

MEDIA ADAPTATIONS

Beloved was adapted as a 1998 film of the same title, starring Oprah Winfrey, Danny Glover, Thandie Newton, and Kimberly Elise, and was directed by Jonathan Demme. Paradise was optioned by Harpo Productions for adaptation as a television miniseries. Several of Morrison's books, including Jazz, Beloved, Tar Baby, Paradise, Song of Solomon, and The Bluest Eye, have been adapted to audio cassette.