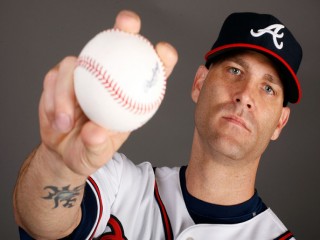

Tim Hudson biography

Date of birth : 1975-07-14

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Columbus, Georgia

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-10-29

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, pitcher with the Atlanta Braves,

0 votes so far

Timothy Adam Hudson was born July 14, 1975, in Columbus, Georgia. He and his brother were raised in a working-class household in nearby Phenix City. Their father, Ronnie, worked in a box factory, eventually rising to the position of plant supervisor. His wife, Sue, was a stay-at-home mom. Instilled with a solid work ethic, both boys were told at an early age that you don’t ever give up. They grew up believing that there is always something there if you just dig deep enough.

Tim (or “Timmy,” as he was known until his 20s) never had the regal bearing of an elite athlete. On amusement park excursions, he recalls, his mortal enemy was the sign that read, “You must be this tall to go on this ride.” Tim may have been on the short and skinny side, but what everyone in his hometown knew about him was that he was rarely on the losing side.

As a youngster, he spent a lot of time with friends running around the wooded areas on the Hudson's five acres of land. Pick-up baseball games were played on a nearby cow pasture. Tim and his buddies were all good kids, and their opportunites to get into trouble were limited.

Tim was quick, he was tough, and he was bright—and he knew how to find imaginative ways to beat the kids he was matched up against. Yet at no time in his childhood did anyone figure he would make much of a pitcher. Tim earned his first mound assignment through sheer persistence, bugging his Little League coach for a start until he final relented. After walking the ballpark, the nine-year-old got the hook. He didn’t throw a ball in anger again until high school.

Tim was a huge Braves fan. He suffered with the team during their down years in the 1980s and thrilled to their worst-to-first pennant run in 1991. The triumverate of Tom Glavine, John Smoltz and Steve Avery (who were later joined by Greg Maddux) intrigued Tim. Little did he know that he would one day be part of a trio compared to the Braves mound corps of the 1990s.

Fueled partly by his love for Atlanta'shurlers, Tim never surrendered his dream of becoming a big-league pitcher, even though his body remained stick-thin. When he enrolled at Glenwood High School in 1989, he worked his way up to the varsity and eventually made the starting staff.

During his time with the team, he became coach Russ Martin’s favorite player. No one competed with more guts or more heart. Tim made himself into a pitcher who wouldn’t lose, not to mention a hitter who would do whatever it took to get to first base. He finished his varsity career with a 12-1 record and a 1.78 ERA, and got the job done at plate, too.

Still on the wrong side of 150 pounds, and not quite six feet tall, Tim was of no interest to college scouts. Upon graduation, he did not receive a single scholarship offer, and no pro team thought he was worth even a last-round pick.

Coach Martin phoned his friend, B.R. Johnson, the baseball coach at the local community college, Chattahoochee Valley. Martin sold him on Tim. Over the next two seasons, the teenager filled out a bit and blossomed into an excellent JuCo hurler. He also became a better hitter, able to play the outfield or DH when he wasn’t on the mound.

Tim showed enough to earn a Division-I scholarship to Auburn, though Tigers coach Hal Baird had his doubts about the skinny hurler. Tim was basically a fastball-curveball guy when he arrived on campus, and both pitches looked hittable by SEC standards. As coach Baird expected, Tim got cuffed around in his first few outings. Baird suggested that Tim drop down a bit from his straight over-the-top delivery and explained the concept behind the split-fingered fastball, which he hoped Tim would think about using the following year.

Three days later, Tim reported that he had mastered the pitch. Baird watched in slack-jawed awe as the junior produced one sharp-dipping delivery after another. The lower arm angle also added life to his fastball and gave his slider more bite.

Auburn had a so-so season, going 20-6 outside the SEC, but only 12-18 against conference rivals. The Tigers were a club devoid of stars, not an enviable position in a league that boasted the likes of Brad Wilkerson, Kit Pellow, David Eckstein, Dustan Mohr, R.A. Dickey, Scott Downs and Player of the Year Eddy Furniss.

ON THE RISE

Tim started, relieved, and played center field for Auburn as a junior and handled himself fairly well. His pitching stats—five wins, three saves, a 3.25 ERA and 90 strikeouts in 75 innings pitched—only hinted at the progress he had made by season’s end. Tim had begun to come into his own as a hurler. His delivery was a thing of beauty, mechanically correct and metronomically consistent from pitch to pitch. He had gained decent command of the splitter and learned to adjust his fastball grip to make the ball do all sorts of ugly things. Pro scouts, never impressed with Tim’s size, finally started to take notice.

Great things were expected of Tim heading into his senior year, but no one was remotely prepared for the numbers he produced. Indeed, Tim had one of the greatest two-way seasons in college baseball history. He batted .396 (8th best in the SEC) in 65 games, with 18 home runs, and his 95 RBIs placed him second in the conference to Brandon Larson, who knocked in 118 for LSU. On the mound, Tim won a league-best 15 games against only two losses and fanned 165 batters, also tops in the SEC. He was an All-SEC pick both as an outfielder and as a pitcher, a first-team All-American at the “utility” position, and was SEC Player of the Year. He also beat out Lance Berkman and JD Drew for the Rotary Smith Award, the collegiate MVP as picked by a poll of Sports Information Directors.

Auburn ended the year with 50 wins, but the team went only 17-12 in conference play to finish fourth in the western division. That was still good enough to earn an NCAA Tournament bid. After elbow soreness limited Tim's participation in the SEC Tournament, he bounced back and was named the Outstanding Player in the NCAA’s East Regional, as the Tigers advanced to the College World Series. They went just 1-2 in the CWS, however, and watched as in-state rival Alabama advanced to the championship game (where the Tide was blown out by Larson and LSU).

The next step for Tim was pro ball. He figured that his size would work against him in the draft, particularly as a hitting prospect, so he hoped that a team would be dazzled by his mound stats. When the A’s selected Tim in the sixth round, they had him listed as a pitcher. That was great. He was never entirely sure he had the stick to make it to the majors, but he knew he had the arm. Tim could get guys out—Period.

Tim was a much-needed departure for the A’s, who had historically gone after imposing young hurlers who threw in the high 90s. They had racked up some spectacular blunders drafting guys like Todd Van Poppel and David Zancanaro. Oakland was willing to look past Tim’s less-than-imposing build.

The A's assigned Tim to South Oregon of the Northwest League in 1997. Concerned about his elbow inflammation, Rick Peterson, the organization pitching coach, asked him to raise his arm angle a bit. Less than a week passed before the pain disappeared, and the fastball that scouts had clocked at 88 mph in college jumped up to 93.

Next, Peterson asked Tim if he would like to learn a changeup. The youngster fooled around with four different grips, settled on one, and then fired the pitch with perfect arm-speed, location, and drop. Tim made four starts and four relief appearances for the Timberjacks and went 3-1. He walked just two batters and convinced the A’s that he was playing way below his level.

In 1998, the A’s moved Tim up to Modesto of the Class-A California League. He made hitters look silly with his splitter and won all four of his decisions before a promotion to Class-AA Hunstville. There he joined a staff that included Brett Laxton and Chris Enochs, and later Eric DuBose, all of whom were recent college stars. The hitters at this level didn’t have a prayer against Tim’s splitter, which had gotten better with each pro start. The pitch was so effective, in fact, that manager Jeff Leonard was told by the Oakland brass to prohibit him from using it until he had two strikes on a batter.

Tim had enough life on his other pitches to get batters out, but he did not always have command of them. This, of course, was what the A’s wanted him to learn. It took a while to adjust, but he got a handle on his slider and sharpened his ability to change speed and location with his fastball in time to turn in a 10-9 record.

The 1999 season found Tim back in Class-AA with Oaklan ’s new minor-league affiliate in Midland of the Texas League. In three starts, he was ridiculously good, which prompted the the club to promote him to Class-AAA Vancouver. After eight starts, he was undefeated with a 2.20 ERA. Michigan State All-American and prized first-round pick Mark Mulder was also on the Canadians’ staff. The tall lefty was expected to be major-league ready some time that year. Pitching at the same level, Tim was clearly miles ahead in his development.

Tim got the call to join the A's on June 7, when the team decided veteran Tom Candiotti had no more flutter left in his knuckler. The rookie started against the Padres the next day and had the San Diego hitters corkscrewing into the ground. Tim notched 11 strikeouts (one short of an 84-year-old league record for Ks in a debut) during the no-decision, and reached base on a walk and a hit in his first two at-bats. In five innings, he gave up seven hits, four walks and three earned runs.

Tim posted his first victory in his next start, against the Los Angeles Dodgers. In seven innings, he struck out seven and allowed just one earned run. He absorbed his first loss against the division-leading Texas Rangers on June 24. Tim would not drop another game until mid-September. During that stretch, he beat Pedro Martinez and Randy Johnson on their home turf. To say Tim made a splash would be an understatement.

Tim was a member of a team that was built around the walk and the home run. Three beefy hitters—Jason Giambi, Matt Stairs and John Jaha—filled the middle of the lineup, combining for 295 bases on balls and 106 round-trippers. Stairs and Jaha were veterans on the downside, but the A’s had great offensive talent on the horizon, including shortstop Miguel Tejada, third baseman Eric Chavez and outfielder Ben Grieve. This trio got valuable playing time in ’99 and kept Oakland competitive in the AL West, despite a payroll under $25 million.

The team’s clubhouse was one of the loosest ever. A lot of kidding, a lot of laughing, a lot of guys acting goofy and enjoying baseball. Tim thrived in this atmosphere, which ehlped him build on his early success.

Oakland’s mid-season pick-up of Kevin Appier, plus a revitalized Gil Heredia, gave the club a respectable starting staff for the first time in a long time. The A’s began to climb in the standings in a year they expected to finish around .500, forcing the organization to make a tough decision. Should they gamble on a playoff berth, or continue looking toward 2000?

The A's decided that their surge was not enough to catch the division-leading Rangers (and not enough to challenge the Boston Red Sox for the AL Wild Card). Instead, they chose to wait ‘til next year and swapped aging closer Billy Taylor for Jason Isringhausen, who was coming back from surgery the year before. Oakland still managed to make things interesting, but in the end, the team finished eight games behind Texas.

Tim fashioned an 11-2 record in 21 starts as a rookie, averaging a strikeout an inning with an ERA just over 3.00. There was nothing fancy about how he was getting hitters out. He came inside to move them off the plate, and then got them to pound his splitter into the ground.

It is a rare thing to make the kind of rookie impact Tim did and then get better the following season. With a winter’s worth of video analysis and the respect of opposing hitters, young starters usually get raked as sophomores. Some adopt radical physical changes and end up on the DL, or worse. Not Tim. After some rocky outings in April, he worked with Peterson to change his pitching patterns, adjusted to the adjustments the hitters had made and reeled off nine straight wins. His record stood at 10-2 in July, when he celebrated his first selection to the All-Star Game. The last time an A’s starter had made the squad, Tim wasn’t shaving yet.

Meanwhile, the offense was chugging along behind the bats of Giambi and rising talents Tejada, Grieve and Chavez. The A’s bolstered their staff for the home stretch with the promotion of lefty Barry Zito, who quickly asserted himself as the team’s second-best starter. That gave Oakland a solid four-man rotation with Appier and Heredia.

Tim won his final seven decisions to finish 20-6. His 20th was his biggest, an eight-inning masterpiece against the Rangers that gave the A’s a 3-0 win when they needed it most. With the game scoreless in the seventh, Tim stalked off the mound after the third out and implored his teammates to get him just one run. Tim’s young catcher, Ramon Hernandez, obliged, singling to center to bring home Jeremy Giambi. Had the A’s not won, a make-up game against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays would have determined the division title.

In the Division Series against the New York Yankees, Heredia outdueled Roger Clemens for a 5-3 Game 1 victory. Andy Pettitte twirled a shutout the next night to even the series. Tim got the call for Game 3 as the series moved to Yankee Stadium. The New York veterans were licking their chops at the thought of facing Tim on their home turf. He kept the Yankees off-balance through eight terrific innings, but some early defensive miscues allowed New York to score three times with just one hit out of the infield. Tim was as guilty as anyone, throwing home late on a comebacker when he should have taken the easy out at first. His blunder enabled New York to tie the score 1-1, and in the same inning, Tim walked Scott Brosius to bring up Derek Jeter with the bases juiced. A sharp grounder was mishandled by Tejada to let another run in. The final score was 4-2.

The A’s came back to knot the series on Zito’s 11-1 win in Game 4, and the teams returned to Oakland for the fifth and final game. The A’s imploded in the first inning, allowing six runs, and wound up losing 7-5. There was little to feel good about after the crushing loss, but the fact that the team’s two young guns had pitched beautifully in baseball’s ultimate pressure-cooker created a lot of excitement as the 2001 season approached.

The A’s entered ’01 with the most exciting 1-2 starters in the league and a new leadoff man in Johnny Damon. As they soon found out, they also had a brilliant young lefty in Mulder, who had gone 9-10 as a rookie but was on his way to a league-leading 21 wins. The other major surprise for Oakland was the invincibility of the Seattle Mariners, who won 116 games. After an 8-18 start, the A’s were basically playing for the Wild Card.

By July, it was clear that no other team would give Oakland much of a fight. Tim cruised to an 18-9 mark. He tightened up his delivery, which improved his ability to hold runners on. That showed up in his 3.37 ERA—the best on the A’s staff. At season’s end, his career record stood at 49-17, and his .742 winning percentage was the best in modern history among pitchers with 50 or more decisions.

Tim’s final victory of the year was his team’s 100th. The A’s went 102-60, becoming the first club in history to come from 10 games under .500 to reach the century mark. That was good enough to earn a return engagement with the Yankees in the playoffs. After Mulder handcuffed the Bronx Bombers in New York in the opener, Tim followed with a masterful performance in Game 2, combining with Isringhausen to shut out the Yankees 2-0. Tim’s opponent, Pettitte, was unbeaten in his last nine post-season outings, so it was a huge win.

The A’s went back to Oakland—where they had won their last 17 straight—looking to wrap things up. Tim recalls scanning the box scores trying to figure out whether he wanted to play the Cleveland Indians or Seattle in the ALCS.

Then the roof caved in. Mike Mussina outpitched Zito in a 1-0 classic that turned on Derek Jeter’s now-famous flip to nail Jeremy Giambi at the plate. The New York hitters lit up starter Cory Lidle in Game 4 to send the series back to Yankee Stadium. In Game 5, Tim entered in the fifth inning in relief of Mulder, with Oakland already trailing 4-3. He allowed a solo homer to David Justice, and the A’s did not score again. For the second year in a row, the Yankees sent Oakland home early.

In 2002, the A’s entered the fray without Jason Giambi, lost to the hated pinstripers via free agency. But Chavez and Tejada, now in their prime years, provided enough pop to make Oakland the league’s top power-hitting club. Billy Koch was brought in to replace departed closer Isringhausen.

The A’s found themselves locked in a heated battle with the Anaheim Angels and Mariners through July. Theyembarked on a remarkable 20-game winning streak that all but decided the division. Tejada was the hitting hero in most of those wins, but Tim and the other pitchers did their part in keeping games close or simply shutting opponents down. Oakland won 103 games to tie the Yankees for the best record in baseball.

Tim finished at 15-9, but pitched far better than his numbers. He left with a lead eight times only to see the bullpen cough it up. He really turned it on after the All-Star break, going 9-2 and ending the year with eight straight victories. His 2.98 ERA was sixth best in the league.

The A’s met the Twins in the division series, with Oakland seen as a prohibitive favorite. But speed, defense and pitching boosted Minnesota to a surprising 3-2 series win, and once again Oakland fell frustratingly short of the World Series. Tim had the worst postseason of his life, fighitng a left side strain thoughout. He surrendered back-breaking big innings in Game 1 and Game 4, both of which the A’s lost. Trailing in the decisive Game 5 5-1 in the ninth, Oakland came up one run short in a valiant comeback against Minnesota closer Eddie Guardado. Koch had given up three runs in the top half of the frame, all but ruining the A’s chances.

After a third straight postseason disappointment, manager Art Howe was let go and replaced with Ken Macha. The A’s looked solid for 2003, as Tim teamed with Zito, Mulder and Ted Lilly to give Oakland an excellent starting rotation. Tejada and Chavez would drive the offense again, with an assist from newcomer Erubiel Durazo.

Oakland managed to keep pace with the Mariners in the first half, and then built a small lead with a 10-game August winning streak. The A’s posted 96 victories and held on to edge Seattle in the AL West. Tim went 16-7 with a 2.70 ERA. Once again, his stats barely did justice to his great season. In his 11 no-decisions, the A’s were 10-1, and four times new closer Keith Foulke blew saves Tim had entrusted to him.

Tim pitched well in the opening game of the ALDS against the Red Sox, but watched a 3-1 lead disappear in the seventh inning when reliever Ricardo Rincon could not slam the door on the Boston hitters. The A’s still managed a 5-4 victory in 12 innings. They won Game 2, 5-1 behind Zito, but could not get the decisive third win in Boston, as the Red Sox gutted out an extra-inning win.

Macha sent Tim out to seal the deal in Game 4. He lasted just 11 pitches before leaving with a strained muscle in his left side—the same injury that had plagued him in the postseason a year earlier. The A’s took a lead into the eighth without Tim, but David Ortiz, mired in a slump, touched Foulke for a two-run eighth-inning double to send the series back to Oakland.

After the game, rumors swirled about a barroom brawl the night before. Tim, his brother and Zito had been at Club Q, near Boston’s Quincy Market, signing autographs, when they had a brief confrontation with rowdy Red Sox fans. According to witnesses, no punches were thrown.

In Game 5, Zito could not reproduce his earlier magic, and the Red Sox scored four times in the sixth to win 4-3 and advance to the ALCS. It was Oakland’s ninth straight loss in a potential playoff-clinching game—an all-time record nobody on the club cared to hear about, least of all Tim, who felt terrible about his early exit two days earlier.

The A’s appeared to be the team to beat in the AL West in 2004, despite losing Tejada to free agency. He was replaced by prospect Bobby Crosby, who went on to win Rookie of the Year honors. Chavez carried the load on offense, with assists from a motley crew including veterans Durazo, Eric Byrnes, Scott Hatteberg, Mark Kotsay and Jermaine Dye. Octavio Dotel, picked up from the Houston Astros midway through the season, filled the closer’s role vacated by Foulke, who inked a free-agent deal with the Red Sox over the winter.

Tim’s '04 season had its ups and downs, much like the rest of the A’s. He pitched brilliantly at times, and when he didn’t have his best stuff, he still managed to get batters out. The Red Sox burned him twice, however, which cost him a shot at the league’s ERA title. The strained left oblique that had bothered Tim in the past kept him off the mound for six weeks in the middle of the season. He came back strong and finished 12-6 with a 3.53 ERA.

The A’s could have used those extra starts. They went down to the wire with the Angels and Rangers in the AL West, finishing second by one game thanks to a late-season surge by Anaheim’s Vladimir Guerrero. With 91 wins, Oakland fell short of the Wild Card, which was claimed by Boston. In retrospect, the team’s 1-8 record against the Bosox in ’04—including Tim’s two losses—killed its postseason chances.

In November, Tim made a decision about the coming year—his last under contract to the A’s. He wanted to remain in Oakland for the rest of his career, but also knew the club might not have the money to retain his services. Instead of enduring a season-long drama, he let GM Billy Beane know that he would consider any offer prior to March 1, 2005 to extend his contract. Failing that, he would play out the year and become a free agent.

Armed with this deadline, the A’s shopped Tim and found several willing trade partners. They eventually settled on the Braves, who sent Oakland a high-level pitching prospect, Dan Meyer, middle man Juan Cruz, and outfielder Charles Thomas. A few days, later, Mulder was dealt to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Tim joined a rotation that included John Smoltz, Horacio Ramirez and Jorge Sosa. After signing a four-year, $47 million contract extension, he settled in for the long haul. The NL East proved more competitive than the experts predicted, but in the end, Atlanta finished where it usually did—on top. Tim had a strained left oblique for the better part of a month and missed a handful of starts. He rebounded to go 14–9 with a 3.52 ERA. The highlight of the year was a brilliant duel with Roger Clemens, which ended in a 1–0 victory for the Braves in 12 innings. Tim also got the win on the day the Braves clinched their 14th straight division title.

The division series against the Houston Astros did not go as well. Tim locked horns with an old nemesis, Andy Pettitte, in the opener and left trailing 5–3. The bullpen gave up five more runs in a 10–5 loss. The clubs split the next two contests, and Tim took the mound for Game 4. He was staked to a 6–1 lead, but the Astros got to him in the eighth inning and the bullpen failed once again. Houston won the series 10 innings later in the longest playoff game in history. It was just the second time as a major leaguer, he had lost a game in which he had held a lead of three or more runs.

Tim had a so-so year in 2006. He made 35 starts and won 13 times for a team in transition. His ERA, however, was 4.85—the highest of his career. The Braves fell short of a 15th straight division crown and finished below .500 for the first time since 1990.

The Braves looked for a bounce-back season from Tim in 2007, and they got it. He went 16–10 with a 3.32 ERA and gave up less than a hit an inning. With a little luck and more support from the bullpen, he could easily have tallied 20 victories. As it was, the Braves won 22 of his 34 starts, and Tim posted a nine-game winning streak that topped the NL.

The Braves were also-rans most of the season. They made a spirited run at a Wild Card berth in September before faltering in the final two weeks. The conclusion of the season was distressing for Tim—but nothing compared to the day in April when he learned that his grandmother and former college teammate Josh Hancock died within hours of each other.

Atlanta's prospects for 2008 are the brightest since Tim joined the team. If Mike Hampton returns to form and Chuck James gives the Braves solid innings, the team stands a great chance of challenging the New York Mets and Philadelphia Phillies for supremacy in the NL East. Tim is heading the starting rotation with Smoltz and Tom Glavine, two of his teenage heroes. From his days in Oakland, he's accustomed to being part of a "Big Three"—and no one enjoys the challenge of proving he can hang with the big boys more than Tim.

TIM THE PITCHER

No matter how you slice it, Tim just isn’t a big guy. Listed at 6-1 and 165 pounds, he’s a lot shorter and a little lighter. For years, everyone underestimated his ability to pitch at a high level, ignoring the fact he has gotten the job done at every level.

Tim's secret is really no secret: His powers of concentration, his attention to detail, and his understanding of how to retire hitters combine to turn his low 90s fastball and dipping splitter into fearsome weapons. Throw in a slider and change, and it can be a long night if you’re one of the guys with a bat in your hands.

Tim’s delivery has been a model of consistency over the years, which has kept batters from guessing what he throws. Early in 2004, he had trouble finding his “balance spot” and his ball wasn’t sinking properly. He added a slight pause and toe tap to his wind-up that seemed to have cured the problem. The timing device was something he had used while warming up before starts.

As a competitor, Tim is as tough as they come. He loves pitching under pressure, and his teammates always feel confident when he takes the mound.

EXTRA

* Tim’s 15 wins in 1997 tied him for the NCAA lead. He also was 9th among the nation’s hitters in RBIs that season.

* When Tim first came up, teammate Jason Giambi called him “Mini-Pedro,” because he could make the ball do as many things as Martinez.

* The only A’s to reach 50 wins in fewer starts than Tim’s 90 were Hall of Famers Rube Waddell (79) and Eddie Plank (89).

* Tim finished fifth in the Rookie of the Year balloting in 1999. He was named AL Rookie Pitcher of the Year by The Sporting News.

* Only one other pitcher in history, Mike Thurman, accomplished what Tim did in 1999, defeating both eventual Cy Young Award winners (Randy Johnson and Pedro Martinez) in the same year. Like Tim, Thurman also turned the trick in 1999.

* Tim led the majors in winning percentage in 2000, and finished runner up to Pedro Martinez in the AL Cy Young voting.

* In 2000, Tim became the seventh Oakland A’s pitcher to win 20 games. The first was Vida Blue in 1971.

* Tim twirled a perfect inning during his All-Star debut in 2000, retiring Jose Vidro, Edgardo Alfonzo and Todd Helton in order. He waited until 2004 to make his second appearance in the Mid-Summer Classic.

* Tim established himself as a player who should not be trifled with in 2000, when he faced down challenges from All-Stars Nomar Garciaparra and Matt Lawton in front of tens of thousands of fans. He also went right at Barry Bonds—but like most young hurlers he paid the price. After brushing him back in a June game that season, Tim watched the slugger deposit the next pitch into the rightfield bleachers.

* Tim beat the St. Louis Cardinals in 2005 for his 100th career victory. He was just the sixth pitcher since 1970 to win 100 times in 202 games or less. The others were Tom Seaver, Andy Pettitte, Dwight Gooden, Roger Clemens and Mike Mussina.

* In 2005, Tim set a record for the most double-digit winning seasons without double-digit losses (7).

* Tim hit the first triple of his career in 2005.

* Tim hurled his second one-hitter in 2006 against the Colorado Rockies. Opposing pitcher Jason Jennings got the only hit.

* Tim’s 10 homers allowed in 224 innings in 2007 was the second-best mark in the majors.

* Tim fanned Tom Glavine for his 1,000th career strikeout.

* Tim says Jim Thome is the toughest batter he's faced.

* Tim won the Roberto Clemente Award in 2006 and 2007.

* Tim got married right after the 1999 season. His wife, Kimberley, is an attorney. They have twos daughter, Kennedie Rose, who was born in the summer of 2001, and Tess, who was born at the end of 2004.

* Tim is one of the most active Braves in the Atlanta community. The last two Christmas's he has hosted a Toys-R-Us shopping spree for kids through the Make A Wish Foundation.