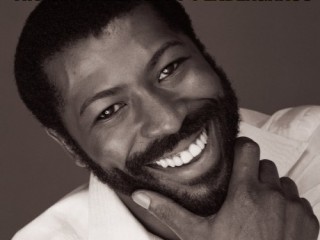

Teddy Pendergrass biography

Date of birth : 1950-03-26

Date of death : 2010-01-13

Birthplace : Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-01-09

Credited as : Singer-songwriter, R&B/soul singer, Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes

0 votes so far

In 1982, he was severely injured in an auto accident in Philadelphia, resulting in his being paralyzed from the waist down. After his injury, the affable entertainer founded the Teddy Pendergrass Alliance, a foundation that helps those with spinal cord injuries. Pendergrass commemorated 25 years of living after his spinal cord injury with star filled event, Teddy 25 - A Celebration of Life at Philadelphia's Kimmel Center. His last performance was on a PBS special at Atlantic City's Borgata Casino in November 2008.

Teddy Pendergrass's fame and fortune were built on his provocative stage presence and the intimate rapport he established with his audiences. Female fans frequently swooned or tossed their undergarments onstage in response to his earthy baritone and forthright sexuality; one fan even went so far as to shoot another in a struggle for a scarf the singer had used to wipe his face. Pendergrass was at the height of his popularity when a car accident left him a quadraplegic--unable to feed or dress himself, let alone execute his charismatic stage moves. He could still sing, however, and within two years of the accident he had released his comeback album. His fans remained loyal, and many critics declared that Pendergrass's tragedy had brought new depth to his music.

Pendergrass began his career in 1968, not as a singer, but as the drummer for Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes. Within two years he had ascended to lead vocalist, and his personal sound came to define the group. In their Encyclopedia of Rock, Dave Hardy and Phil Laing described Pendergrass's singing on Blue Notes hits such as "The Love I Lost," "I Miss You," and "If You Don't Know Me by Now," as "tough, powerful ... mixing the styles of gospel and blues shouters whose intense delivery blended bravado and impassioned pleading in equal measure." He combined an "earthy, sexual insistence on the more aggressively paced pieces with mellow, moodier vocal work on ballads, which he'd gradually infuse with wilder, improvised and often quite histrionic outbursts."

In 1977, Pendergrass left the Blue Notes to pursue a solo career. Women were even more enthusiastic about seeing him alone on stage than they had been about watching him front the Blue Notes. They flocked to special "For Women Only" midnight shows to hear Pendergrass sing "Close the Door," "Turn Off the Lights," and other hits. As a solo performer, Pendergrass expanded his range to attract new listeners: a Stereo Review writer noted that while he still "belted out his funky amorous entreaties with a raw virility that set many female libidos a-quiver," he had also learned to "set aside his club and loincloth to sing tenderly," thereby "reaching both those who like sweetness and those who prefer swagger." Nearly all his albums went platinum, and Pendergrass was acknowledged as the premier black sex symbol of the late 1970s.

Things changed dramatically on March 18, 1982. While Pendergrass was driving his Rolls-Royce through Philadelphia's Germantown section, the vehicle jumped the center median and crashed into a tree. Pendergrass told Life: "[After] the initial bang I opened my eyes, and I was still there. For a while I was conscious. I know I had broken my neck. It was obvious; I tried to make a move and I couldn't." Pendergrass was correct in thinking that his neck was broken; his spinal cord was also crushed, and bone fragments had severed some vital nerves. Movement was limited to his head, shoulders, and biceps. When the full extent of the damage became apparent and doctors told him that his paralysis would probably be permanent, Pendergrass cried until his "eyes looked like golf balls," he told Life. He was further informed that injuries such as his usually affect the breathing muscles and, consequently, the ability to sing. Several days after the accident, Pendergrass cautiously tested his voice by singing along with a coffee commercial on television. "I could sing," he remembered, "and I knew that anything else I had to do, I could do."

Pendergrass's first task was to ride out the ugly rumors that surrounded his mishap. He had been driving on a suspended license, and stories quickly spread that he was drunk or drugged when it occurred. After investigating the incident, Philadelphia police announced that they found no evidence of substance abuse in connection with it, although they speculated that reckless driving and excessive speed were involved. Next, it was revealed that Pendergrass's passenger, Tenika Watson, who was not seriously injured in the crash, was a transsexual entertainer. The former John F. Watson admitted to some thirty-seven arrests for prostitution and related offenses over a ten-year period. This news was potentially very damaging to Pendergrass's image as the ultimate macho man, but his fans quickly accepted his statement that he had merely offered a ride to a casual acquaintance and had no knowledge of Watson's occupation or history.

Once released from the hospital, Pendergrass faced the difficult period of adjustment to his new limitations. From the outset, he was determined that his handicap would not stop his career. "I thrive on whatever kind of challenge I have to face" he told Charles L. Sanders in Ebony. "My philosophy has always been 'Bring me a brick wall, and if I can't jump over it I'll run right through it." After months of special therapy, including exercising with a heavy weight on his stomach in order to build up his weakened diaphragm, Pendergrass recorded Love Language. It became his sixth platinum album, affirming both his musical abilities and his fans' loyalty. Another milestone in the singer's recovery came at the 1985 Live Aid concert, when he made his first stage appearance since the accident, singing "Reach Out and Touch" with Ashford and Simpson. "I don't know how to fully describe those few moments onstage," he confessed in People. "Before I went on, I was scared, afraid of the unknown. Afterward I felt like I was larger than anybody there. It reaffirmed one very important fact to me, that it wasn't important that I shook my booty right or that I had legs that turned a certain way. What the audience most appreciated was what I was saying in the song."

"I ain't going to lie, this thing's a bitch," Pendergrass said of his paralysis. "You go through living hell, through all kinds of anxieties, and you suffer enormous apprehensions about everything. At first you don't know how people will accept you, and you don't want to be seen. You don't want to do anything. Given thoughts like that, you don't want to live. But ... you have an option. You can give it up and call it quits, or you can go on. I've decided to go on."

Solo LPs:

-Life Is a Song Worth Singing Philadelphia International, 1978.

-Teddy Philadelphia International, 1979.

-T.P. Philadelphia International, 1980.

-Live Coast to Coast Philadelphia International, 1980.

-It's Time for Teddy Philadelphia International, 1981.

-Teddy Pendergrass Philadelphia International, 1982.

-This One's For You Philadelphia International, 1982.

-Heaven Only Knows Philadelphia International, 1983.

-Greatest Hits Philadephia International, 1984.

-Love Language Asylum, 1984.

-Workin' It Back Asylum, 1985.

-Joy Asylum, 1988.