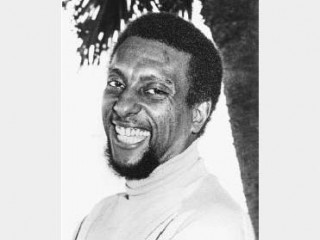

Stokely Carmichael biography

Date of birth : 1941-06-29

Date of death : 1998-11-15

Birthplace : Port of Spain, Trinidad

Nationality : Trinidadian-American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-08-31

Credited as : Black activist, civil rights movement, "Black Power"

0 votes so far

Inspiration in New York

Stokely Carmichael was born Kwame Ture in Port of Spain, Trinidad, on June 29, 1941. His father moved his family to the United States when Stokely was only two years old. In New York City's Harlem neighborhood, Carmichael's self-described "hip" presence quickly made him popular among his white, upper-class schoolmates. Later his family moved to the Bronx, where Carmichael soon discovered the lure of intellectual life after being admitted to the Bronx High School of Science, a school for gifted students.

Carmichael's political interests began with the work of African American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin (1910–1987), whom he heard speak many times. At one point Carmichael volunteered to help Rustin organize African American workers in a paint factory. But the radical and unfriendly views of Rustin and other similar African American activists would eventually push Carmichael away from the movement.

The civil rights movement

While Carmichael was in school in the Bronx in the early 1960s, the civil rights movement exploded into the forefront of American culture. The Supreme Court declared that school segregation (separating people based on their race) was illegal. African Americans in Montgomery, Alabama, successfully ended segregation on the city's buses through a yearlong boycott. During the boycott, they recruited others to stop using the buses until the companies changed their policies. During Carmichael's senior year in high school, four African American freshmen from a school in North Carolina staged a famous sit-in, or peaceful protest, at the white-only lunch counter in a department store.

The action of these students captured the imagination of young Carmichael. He soon began participating in the movements around New York City. Carmichael also traveled to Virginia and South Carolina to join sit-ins protesting discrimination (treating people differently based solely on their race).

Joining the movement

Carmichael refused offers to attend white colleges and decided to study at the historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C. At Howard, Carmichael majored in philosophy and became more and more involved in the civil rights movement.

Carmichael joined a local organization called the Nonviolent Action Group. This group was connected with an Atlanta-based civil rights organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Whenever he had free time, Carmichael traveled south to join the "freedom riders," an activist group that rode interstate buses in an attempt to end segregation on buses and in bus terminals.

Although the "freedom riders" gained support in some parts of the country, they met resistance in other areas, especially the South. Some of the freedom rider buses were bombed or burned. The riders themselves were often beaten and jailed. In the spring of 1961, when Carmichael was twenty, he spent forty-nine days in a Jackson, Mississippi, jail. One observer said that Carmichael was so rebellious during this period that the sheriff and prison guards were relieved when he was released.

After graduating in 1964 with a bachelor's degree in philosophy, Carmichael stayed in the South. He constantly participated in sit-ins, picketing, and voter registration drives (organized gatherings to help people register to vote). He was especially active in Lowndes County, Alabama, where he helped found the Lowndes County Freedom Party, a political party that chose a black panther as its symbol. The symbol was a perfect choice to oppose the white rooster that symbolized the Alabama Democratic Party.

Turning from nonviolence

The turning point in Carmichael's experience came as he watched when African American demonstrators were beaten and shocked with cattle prods by police. With his activism deepening and as he saw the violence toward both violent and nonviolent protesters, he began to distance himself from nonviolent methods, including those of Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968).

In 1965 Carmichael replaced the moderate John Lewis (1940–) as the president of the SNCC. He then joined Martin Luther King Jr. in his now famous "Freedom March." King led thousands from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to register black voters. But Carmichael had trouble agreeing with King that the march should be nonviolent and that people from all races should participate. During this march Carmichael began to express his views about "Black Power" to the media. Many Americans reacted strongly to this slogan that some people believed was antiwhite and promoted violence.

"Black Power" and backlash

Carmichael's ideas of "Black Power," which he turned into the book Black Power (coauthored by Charles V. Hamilton), and his article "What We Want," advanced the idea that racial equality was not the only answer to racism in America. Carmichael and Hamilton linked the struggle for African American empowerment, or the process of gaining political power, in America to the end of imperialism worldwide (or the end of powerful countries forcing their authority on weaker countries, especially those in Africa).

With racial tensions at an all-time high, journalists demanded that Carmichael define the phrase "Black Power." Soon Carmichael began to believe that no matter what his explanation, the American public would interpret it negatively. In one interview, Carmichael spoke of rallying African Americans to elect officials who would help the black community. However, Carmichael sometimes explained the term "Black Power" in a different way when he spoke to African American audiences. As James Haskins recorded in his book, Profiles in Black Power (1972), Carmichael explained to one crowd, "When you talk of 'Black Power,' you talk of building a movement that will smash everything Western civilization has created." Carmichael and his movement continued to be seen by many in America as a movement that could spark a "Race War."

With the civil rights movement in full swing, the SNCC became more of a way to spread Carmichael's "Black Power" movement. When Carmichael declined to run for reelection as leader of the SNCC, however, the organization soon dissolved.

An international focus

By this time, Carmichael's political attention had shifted as well. He began speaking out against what he called U.S. imperialism (domination of other nations) worldwide. Reports told of Carmichael traveling the world making statements against American policies in other countries, especially America's involvement in the Vietnam War (1955–75), a war fought in Vietnam in which the United States supported South Vietnam in its fight against a takeover by Communist North Vietnam. These reports only fueled dislike and fear of Carmichael in the United States.

In 1968, the radical and violent Oakland, California-based Black Panther Party made Carmichael their honorary prime minister. He resigned from that post the following year, rejecting Panther loyalty to white activists.

Carmichael then based himself in Washington, D.C., and continued to speak around the country. In May 1968 he married South African singer-activist Miriam Makeba.

Leaving America behind

In 1969 Carmichael left the United States for Conakry, Republic of Guinea, in West Africa. While in Guinea, Carmichael took the name Kwame Ture. Over the next decades, he founded the All-African Revolutionary Party.

Unlike many of his peers who emerged from the civil rights movement, Carmichael's passion and beliefs always remained strong. He continued to support a revolution as the answer to the problems of racism and unfairness until his death from prostate cancer on November 15, 1998, in Conakry, Guinea.