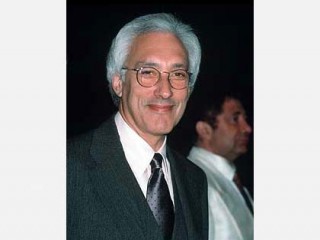

Steven Bochco biography

Date of birth : 1943-12-16

Date of death : -

Birthplace : New York City, New York, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-09-07

Credited as : Television producer and writer, producer television films as "Hill Street Blues", "The Invisible Eye" , "Bay City Blues"

0 votes so far

"I want to do stuff that challenges folks and entertains folks, and I'm willing to take the risk that some people will not like what I do." That attitude some say has changed the face of television, and it belongs to producer Steven Bochco, speaking to Robert Lindsey in the New York Times Magazine. As a maverick creator of acclaimed and sometimes controversial series such as Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law, NYPD Blue, and Over There, Bochco routinely explores complex, realistic, adult situations fraught with violence, moral ambiguity, and sex. Critics have commended his series for tackling such difficult issues as incest, legal ethics, and police violence without oversimplifying or offering easy answers.

Like most producers, Bochco surrounds himself with teams of writers and a support staff to help him meet the hectic pace. Just as his best-known shows use an ensemble cast, the stories themselves--and even the characters--are created by a committee. Bochco has final say over every script, and he is most often personally responsible for the placement of scenes in the program's final cut. More importantly, Bochco himself undertakes the most harrowing aspects of television production, including conceiving new show ideas, demanding ample budgets, and defending his more graphic scenes and language against censorship by the network's "standards and practices" division. Bochco's aggressive maneuvers within the corporate environment--his stubborn refusal to give up control over his shows--have earned him enemies as well as admirers. "Steve's a difficult guy," former employer Grant Tinker told the New York Times. "I think he's somewhat free-form and somewhat erratic in his work habits, but he's very, very, talented. He is very competitive in a way that he probably wouldn't admit. He wants to do better than the other guys, and he won't let up."

Bochco was born into a family of modest financial means. From his childhood he was shadowed by financial worries because his father, concert violinist Rudolph Bochco, "didn't have a knack for making money," as the producer told Paula Span in Esquire. The family "held onto its ... apartment and never went without shoes, food, or a Steinway," Span reported, "but he could not provide them with financial stability." Rudolph urged his son toward a practical career, perhaps in engineering, but Bochco was more interested in sports, girls, and singing than studying. "My adviser informed me that I was not college material," he recalled in a Rolling Stone article by Mark Christensen. Despite that judgment, Bochco managed to win a scholarship to New York University.

Encouraged to Pursue Writing

When Bochco transferred to Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie-Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, the idea of a writing career began to take root. "I'd always written stuff," Bochco told Christensen. "And even in high school, teachers had told me I was talented, encouraged me. Now, all of a sudden, I was surrounded by people with whom I shared common interests." Bochco's friends at Carnegie included Charles Haid and Bruce Weitz--both of whom would later be cast as policemen on Hill Street Blues--and Michael Tucker, who would eventually become a regular on L.A. Law. Also while at Carnegie, Bochco met Barbara Bosson, his future wife and a cast member of Hill Street Blues and Hooperman. A summer internship got his foot in the door at Universal Studios, and when he graduated from college, he landed a full-time job there. "I didn't wait for my grades, my diploma, anything," he remembered in Rolling Stone. "Michael Tucker and I piled into my car and drove fifty-two hours from Pittsburgh to L.A. We were going to make our fortunes. It was wonderful."

Bochco's work for Universal, which at that time was regarded as something of a television factory for the way it churned out shows, was not glamorous. "What I did when I first started there--and it was tremendous hands-on training--was take unsold pilots and episodes of 'Chrysler Theatre' and write an additional hour's material for them," Bochco explained in American Film. "It would be filmed, spliced in, and the whole thing released as an overseas movie package for television. Really, it was very smart business." Bochco found himself doing well. "I ended up pulling down $15,000 my very first year," he told Christensen. Bochco's father was "happy, excited and nervous" about the job--nervous that his son would make a wrong move. "Because I don't think he'd ever made $15,000 a year in his whole life."

In 1970 Bochco became story editor on a promising new detective series, Columbo, which he assessed in American Film as "probably the single most fortunate thing that ever happened to me." The period was memorable for several reasons. For one thing, Bochco worked with director Steven Spielberg years before the latter became famous. As he recalled: "The episode of 'Columbo' that Steven directed was the first one I ever wrote. And the two of us were really the baby boys at Universal.... I was twenty-six and Steven was twenty-two." Also, he noted, "because of 'Columbo''s success, I gained a degree of professional recognition in the business that I hadn't had before." That recognition included his first two Emmy Award nominations for writing.

From Screenwriting to Producing

Universal also called upon Bochco to do some writing for feature films. He helped to write the screenplays for The Counterfeit Killer and Silent Running. The latter, a 1971 film about a spaceborne botanist's efforts to preserve Earth's last vegetation following a nuclear war, helped push Bochco into producing. "I watched them make this thing, and I hated it," he complained in American Film. "I was so disturbed, as I guess most writers are, at seeing the terrible disparity between what was in my head and what they were putting on the screen, that I thought: I've got to be able to do something about this.... I started producing the next year." Producing his own works--using his own money to create the television shows--gave him the control he wanted. But Bochco confessed that in the beginning he was an "awful producer," and his first several television projects lasted only a season or two. By 1978 he was ready to move on.

A few years after leaving Universal for MTM Enterprises, home of such successful programming as The Mary Tyler Moore Show and its spin-off series Lou Grant and Rhoda, Bochco got an assignment to create a new police drama. He had already written for a number of crime shows, including Columbo, McMillan and Wife, and Delvecchio, and neither he nor his collaborator, Michael Kozoll, relished another. However, Fred Silverman, the president of NBC Entertainment, put a different twist on the idea. He thought the series should have "an emphasis on personal lives. That put a bulb over my head," Bochco told Christensen in a Rolling Stone article. After that flash of inspiration, the show was "a genuine ensemble invention," he remarked in American Film. Bochco ultimately received much of the credit for its success, but as he put it, "I just wound up having the mouth."

Hill Street Blues

Bochco and Kozoll enlarged the number--and the psychological dimensions--of the series' characters, creating an ensemble cast rather than the traditional one or two leading characters. The pilot episode of Hill Street Blues uncovers both the personal and professional lives of some fictitious inner-city policemen, and the unusual carrying-over of plots from one week to the next followed thereafter. The show started with eight regular characters and a style borrowed from The Police Tapes, a documentary program filmed in black-and-white with hand-held cameras. Aware that developing so many characters complicates plot structure, they "began to think of it more in terms of a tapestry," Bochco noted in American Film. Plots and subplots could then overflow from one episode to the next instead of being tied up neatly at the end of each hour. Conventional series plot resolutions did not satisfy Bochco anyway. "If you have neatness in 48 minutes, you've got to end up earnest, pedantic, didactic, and finally arrogant," he told Tony Schwartz in New York. Overlapping dialogue, a freer use of idiom, and camera angles that take in a broad picture, with characters moving through scenes from all sides, added to the illusion of reality. Unexpected and sometimes shocking plot twists created tension and held viewers' attention.

Hill Street Blues premiered mid-season, in January 1981, and reviews were mixed and ratings low, at least at first. Some writers criticized the characters' many eccentricities, the way the show combines serious and comic elements, and what they considered gimmicky production techniques. Others, like Film Comment reviewer Richard T. Jameson, welcomed it as "one of the best series ever developed for television." Marveling at its free-flowing structure, Jameson remarked: "I have never encountered another TV program that betrayed less sign of anticipating commercial breaks or straining to tie off tonight's episode." John J. O'Connor, writing in the New York Times, found that Bochco's series "takes chances": It sometimes "falls on its face, but its attempts to break the shackles of standard formats are rarely uninteresting."

Often uncompromisingly violent, Hill Street Blues portrays the day-to-day events in a ghetto district police precinct and features an open explorations of drug abuse, alcoholism, racism, child abuse, and marital infidelity. Todd Gitlin noted in Inside Prime Time that the series is "as good as series television has gotten.... Intelligent writing, it seemed, had its appeals; so did some unusually good acting, the serial form, ensemble work, an interesting texture. Complexity of plot and atmosphere did not intimidate ten or fifteen million American households."

Despite positive reviews, the gritty police drama was plagued with sagging ratings for most of 1981. As Christensen reported, Hill Street Blues was "the lowest-rated series ever to be renewed at the end of its first season." Bochco and his colleagues proved ratings were not all that mattered in the fall of that year, however, when their series captured an unprecedented eight Emmy awards. Crowning the honors were awards for best drama series and best writing in a drama series, which Bochco shared as co-producer and coauthor. Emmy awards, however, were no guarantee of Hill Street Blues' survival, as Richard Corliss warned in Time. Corliss hoped the exposure from the awards might convince viewers to tune in to the "ferociously intelligent" series, which he considered "very much its own show."

In his New York Times Magazine interview, Bochco explored the fundamental difference between television's aims and his own: "Television is not an art medium.... It is really a commercial sales medium. It does not want to do anything to encourage controversy or distress. The ideal piece of programming for selling things, I suppose, lulls you into a pleasant sense of well-being.... There's nothing wrong with that, but ... that's not what I want to do."

Hill Street Blues' high price tag eventually caused strife between Bochco and MTM. "We were the most responsibly produced series on television," he insisted in Rolling Stone, telling Christensen: "When you figure a very modest feature film comes in today at about $8 million, we were delivering comparable production values for about $1 million." That price tag was still well over the cost of more traditional police shows, however. Part of the trouble was that to achieve such a high degree of realism, producers frequently filmed on location instead of in a manufactured set. Multiple characters and complicated plotting also drove costs up. Recalled Bochco: "Money was a subject I fought with MTM about from the second year on." He maintained that "there are only two ways to make a cheaper Hill Street. One, reduce the number of characters--which leads to the second, reduce the number of stories." Either tactic, Bochco argued, would damage the series. Because the show did eventually improve its ratings and continue to win awards, MTM stuck with it, albeit reluctantly.

Financial Impasse Signals Series End

By 1985 Bochco's rocky relationship with MTM had become unsalvageable. Quipped Christensen in 1986, "It's not every day that the best producer in dramatic television is fired from the best TV production house in Hollywood for the high crime of having the best show in prime time." The split reportedly had several causes. The cost of Hill Street Blues had been a long-standing issue, but Bochco told Christensen: "I was not asked to leave MTM because I produced an expensive show that I refused to make less costly.... No, it was personal. They didn't want me.... Some people consider me difficult." Once Hill Street Blues reached the golden moment for a series--enough completed episodes to go into syndication, where it might make as much as one million dollars per episode--MTM let Bochco go.

Hill Street Blues was, wrote Todd Gitlin in his book Inside Prime Time, "a mature and even brilliant show that violated many conventions, pleased critics, caught the undertow of cultural change, and ran away with the Emmys." Span in Esquire contended that Hill Street Blues "changed television itself. Into the conventional few-good-men police plot, it wove the stuff of aching, infuriating, ridiculous reality, too much to shoehorn into an hour." It was "as intellectually and emotionally provocative as a good book," claimed author Joyce Carol Oates in TV Guide. "In fact, from the very first, Hill Street Blues struck me as Dickensian in its superb character studies, its energy, its variety; above all, its audacity."

Though ousted from the show that had brought him fame, Bochco had no lack of options when he left MTM. He chose Twentieth Century-Fox, where he dealt frankly with his big-spender reputation. Christensen quoted Bochco as explaining: "The only thing I said was, 'Look, if you'd like me to build you a Rolls-Royce, I'll build you a Rolls-Royce. If you'd like me to build you a Chevrolet, I'll build you a Chevrolet. But please do not ask me to build you a Rolls for the price of a Chevy.'" Bochco's first project for his new employer was the upscale legal drama L.A. Law. Like Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law was an ensemble series with a documentary flavor, interwoven stories, and a taste for controversy. This time, however, Bochco and his colleagues intended to keep costs under control. On-location filming gave way to a studio set, and the number of recurring characters dropped to a more manageable nine or ten. Striving as ever for authenticity, Bochco got help with legal details and scripts from lawyer/writer Terry Louise Fisher, who had previously been a producer for another successful police show, Cagney and Lacey. Together they created a series that "moves the profession into the litigious real world," as Richard Zoglin put it in Time.

A Pragmatic Courtroom Drama

Characterization proved one of the show's most distinctive aspects to critics. Whereas previous law series had featured sleuths like Perry Mason or high-minded crusaders as in The Defenders, Bochco and Fisher's attorneys often appeared as "unprincipled hired guns who, uninterested in truth or justice, go for the jugular to win a case and make a buck," observed Lindsey. Bochco felt that this portrait struck closer to reality and public opinion. As he remarked to Lindsey: "I think the general impression that a lot of lawyers are jerks is not without some validity." In a Time article assessing Bochco's influence, Zoglin quipped: "Bochco's sly accomplishment is to have concocted a show that, while styling itself as a no-holds-barred look at the legal profession, manages to reaffirm a host of romantic illusions about lawyers.... The show says you can have your ideals and your BMW too."

Like Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law impressed award-givers, repeating the earlier series' feat of capturing Emmy awards for best dramatic series and best writing for a dramatic series, among others. The series also became an even bigger hit with viewers than Hill Street Blues had been. L.A. Law continued to win awards and settled in for a run of more than seven years.

Captures Younger Audience with Medical Drama

In 1989 Bochco launched Doogie Howser, M.D., which details the personal and professional trials of a boy who earns a medical degree at age fourteen and is a second-year hospital resident at age sixteen. It was inspired in part by Bochco's father, who at age nine was already a professional violinist. When Bochco was a child, "prodigy didn't mean anything to me," he confessed to Diane Haithman in the Los Angeles Times. "All I knew was I had a dad who was a violinist--that's what he did professionally. But he was also a guy who was a gifted portrait painter, self-taught, a wonderful architect, self-taught, a wonderful designer and master-builder, a voracious reader.... He audited medical school when he was a 20-year-old kid, because he had a bunch of friends who were medical students." Doogie Howser, M.D. became something of a tribute to Bochco's dad, right down to the computer-animated violinist that ran as the logo for Steven Bochco Productions at the end of each episode.

"Every kid's fantasy is of being empowered, like an adult," Bochco told Detroit Free Press writer Marc Gunther. "That's what adolescents rail against. Their parents are collaring them, yanking on that leash. They want to have what seems to be the unbridled fun and freedom and mobility of an adult." For Bochco, Doogie Howser is "a kid who is living that fantasy and discovering, in many, many, many ways, every day of his life, hopefully with some fun attached to it, that it's an awesome responsibility, being free." The pilot episode focused on Doogie's sixteenth birthday, for which his colleagues stage a prank seduction that proves decidedly less funny to the sixteen-year-old than to the adult staff. "Although later episodes might be lighter," Bochco explained to Haithman, "my choice was to do something that aches, so you could see what is fundamental to the concept--the compelling complexity and difficulty of being a boy in an adult world." Reviewing the new series for the Detroit Free Press, Susan Stewart pronounced it "flawed-yet-interesting.... There is nothing here to criticize, and nothing to compel anybody to keep watching. Unless we are 14-year-old girls." Stewart acknowledged the appeal of teenage star Neil Patrick Harris and likened Doogie to television's much-loved Dr. Kildare, with the added charm of being "young enough to take you to the prom." Young viewers flocked to the show, which lasted four seasons.

Returns to Mean Streets with NYPD Blue

In 1993 Bochco launched the series NYPD Blue. Julie Salamon, writing in the New York Times, found that "in crucial ways the show continued a tradition begun more than a decade earlier in Hill Street Blues, another Bochco cop show.... Hill Street pioneered a new kind of police drama, constructed as a soap opera, peopled with a rich assortment of characters. The good guys were often as flawed as the bad guys. No one expected to triumph against evil; they were more concerned with simply making it through the day."

Despite its similarities to Hill Street Blues, NYPD Blue contained "more adult language and themes--not to mention partial nudity--than network television had been accustomed to," according to Gloria Goodale in the Christian Science Monitor. Network resistance to the show's groundbreaking subject matter and language was quickly overcome when the high ratings made it clear that the audience was satisfied with the show. NYPD Blue went on to enjoy a remarkable twelve seasons before coming to an end in 2005.

Bochco created the television series Over There, a fictionalized account of U.S. troops in the Iraq War, in 2005.

The concept was something fresh--a television series about a war that was still in progress--but the show was plagued with difficulties from the start because of conflicting political expectations from both critics and the television audience. Leftist opponents of the war wanted the show to criticize the administration. Supporters of the war thought it demoralized those on the home front. Speaking to Benji Wilson in the London Daily Telegraph, Bochco was optimistic about the response to the show: "I just figure as long as people are on both sides of it that means we're sort of equal-opportunity offenders ... and that means that we're doing our jobs right." Despite his optimism, the series lasted only one season.

Pursuit of the new, daring, or even outrageous is characteristic of Bochco's style. As former NBC chair Grant Tinker told Zoglin: "He rocks the boat as a hobby." Chris Gerolmo, co-executive producer of Over There, told Wilson: "Steven knows arguably more about serial television storytelling than anybody else in the country. He's had a show on one network or another for 25 years in a row and he's still very open to ideas, willing to take chances and try things differently." Bochco explained his approach to Zoglin, noting: "I never imagined the tyranny of success--the way you have to deal with a new standard of excellence.... Do you play the game not to lose? Or do you keep going for a win--pushing it a bit or doing it better or different?" "I think the most amazing thing about my career," he told Christensen, "is that I've never had any specific goals and ambitions. I like the process. I like the work. I have no idea what I'll do next."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born Stevan Ronald Bozovic, December 16, 1943, in New York, NY; son of Rudolph (a concert violinist) Bochco; married Barbara Bosson, 1969 (divorced 1998); married Dayna Kalins, August 12, 2000; children: (first marriage) Melissa, Jeffrey.

AWARDS

William Morris Agency fellowship, 1960s; MCA writing fellowship, 1960s; Emmy Award nominations for best writing in drama for a single program in a series, American Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, 1972, 1973, both for Columbo; Emmy awards for best drama series, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, all for Hill Street Blues, and 1987, 1989, both for L.A. Law; Emmy awards for best writing in a drama series, 1981, 1982, both for Hill Street Blues, and 1987, for L.A. Law; Humanitas Prize for one-hour program, Human Family Institute, 1981, for Hill Street Blues; Edgar Allan Poe Award, Mystery Writers of America, 1981; George Foster Peabody Broadcasting Award, University of Georgia's Henry W. Grady School of Journalism and Mass Communication, 1981; Writers Guild Award, 1981; Hill Street Blues received People's Choice Award for new dramatic program, Proctor & Gamble Productions, and People's Choice Other Award, both 1982, Rockie awards for continuing series, Banff Television Festival, 1982, 1983, 1985, Golden Globe awards for best drama series, Hollywood Foreign Press Association, 1982, 1983, and People's Choice awards for dramatic program, 1983, 1984; L.A. Law received People's Choice Award for new dramatic program, 1987, People's Choice awards for dramatic program, 1988, 1989, and Golden Globe awards for best drama series, 1987, 1988; Doogie Howser, M.D. received People's Choice Award for new comedy program, 1990; Image Award, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Brandon Tartikoff Legacy Award, 2006.

CAREER

Universal Studios, Los Angeles, CA, overseer of internship program, summer, 1960s, scriptwriter, editor, and producer for television and film, 1966-78; MTM Enterprises, Studio City, CA, writer and producer, 1978-85; Twentieth Century-Fox, Los Angeles, writer and producer, 1985-87; Steven Bochco Productions, Los Angeles, chairman and CEO, 1987--. Producer and executive producer for television, including films Lieutenant Schuster's Wife, 1972, and Vampire, 1979; television series Griff, 1973-74, The Invisible Man, 1975-76, Richie Brockelman, Private Eye, 1978, Paris, 1979-80, Hill Street Blues, 1981-85, Bay City Blues, 1983-84, L.A. Law, 1986-89, Hooperman, 1987-89, Doogie Howser, M.D., 1989-93, Cop Rock, 1990, Civil Wars, beginning 1991, Capitol Critters (animated), 1992, NYPD Blue, 1993-2005, Murder One, 1995-97, Brooklyn South, 1997-98, City of Angels, 2000, Philly, 2001, Over There, 2005, and Commander in Chief, 2005-06; and television pilots The Invisible Man, 1975, Richie Brockelman: Missing Twenty-four Hours, 1976, and Every Stray Dog and Kid, 1981. Creator of series Sarge, 1971-72.

WORKS

* SCREENPLAYS

* (With Harold Clements) The Counterfeit Killer (based on television movie The Faceless Man), Universal, 1968.

* (With Michael Cimino and Deric Washburn) Silent Running, Universal, 1971.

* TELEVISION SCRIPTS

* (With Bernie Kukoff) Lieutenant Schuster's Wife (movie), American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. (ABC), 1972.

* Double Indemnity (movie), ABC, 1973.

* The Invisible Man (pilot), National Broadcasting Company (NBC), 1975.

* (With Stephen J. Cannell) Richie Brockelman: Missing Twenty-four Hours (pilot), NBC, 1976.

* (With Michael Kozoll) Vampire (movie), ABC, 1979.

* (With William Read Woodfield) Columbo: Uneasy Lies the Crown (movie), ABC, 1990.

* OTHER

* Death by Hollywood (mystery novel), Bloomsbury (New York, NY), 2003.

* Works in Progress

* Developing television series, including Hollis & Rae.