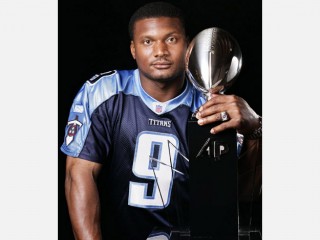

Steve McNair biography

Date of birth : 1973-02-14

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Mount Olive, Mississippi, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-10

Credited as : Football player NFL, quarterback for the Tennessee Titans and Baltimore Ravens, Super Bowl

0 votes so far

Steve LaTreal McNair—the fourth of five sons—was born to Lucille and Selma McNair on February 14, 1973. The McNairs’ marriage ended when Steve was eight, leaving his mom to watch over five rambunctious boys by herself. One of 11 children herself, Lucille knew something about single-parenting. She and her siblings had been raised by her mother, “Grandma Hattie.” The experience forced them to pull together and taught Lucille the importance of a strong and loving family.

Life was often very hard for the McNairs. The family lived in Mount Olive, a small farming town in Mississippi about 100 miles north of the Chandeleur Sound. Their modest home was located on Clarence Deen Road, named for the man who resided at the end of it. Steve and his brothers woke up each morning to feed the chickens and pigs, pick vegetables, and get a jump on their other chores.

Lucille worked the graveyard shift at a nearby electronics factory, starting after the boys were in bed and coming home as they finished their breakfast. She made less than $200 a week. Though money was rarely available for new clothes or toys or athletic equipment, the McNair boys never complained.

Steve was a lot like his mother—determined and patient. And while all of the McNairs were athletic, Steve was something special. Among other things, he could scramble into a tree’s high branches in seconds. This ability earned him the nickname “Monk” from Lucille, who said he looked like a monkey going up a tree. Steve was tough, too. Lucille recalls the time when Steve burned his hand after setting a pile of leaves on fire. She bandaged the wound, and soon he was back to his old self.

Steve was supremely talented in every sport he tried,but football was his favorite. In pickup games on a field the neighborhood kids called “Mount Olive Arena,” he could out-run and out-throw all of his friends. The contests were usually rough affairs, and Steve sometimes came home with tears in his eyes. But he seemed to thrive on the physical punishment. Indeed, a bump, bruise or bloody lip only made him want to play better.

Steve’s only real source of frustration as a kid was walking in the shadow of his oldest brother, Fred. The quarterback for Mount Olive High School, he Fred was the town’s biggest celebrity. As much as Steve admired his brother, he also hated being compared to him. Lucille squelched the potential sibling rivalry when she told Steve that Fred could be the perfect role model. He pondered the advice, and then decided his mom was right. Steve began to attend all of Fred’s practices, tossed the football with him whenever possible, and talked about the nuances of playing quarterback. The youngster soon started to dream about a career in the NFL.

Steve entered Mount Olive as a freshman in the fall of 1987. The 13-year-old quickly developed into a four-sport star (in football, basketball, track and baseball) for the Pirates. The Seattle Mariners were impressed enough to offer him a contract in 1990. The money was tempting, but Steve, Fred and Lucille all agreed that he should turn it down. Being an NFL quarterback was his primary goal, and all three felt it was within his reach.

By this point, Steve was ranked among the nation’s top high-school signal callers. As a junior, he led Mount Olive to the state championship. In his senior season, he shattered all of Fred’s records. Steve might have been an even better free safety than a quarterback. In 1990 alone, he picked off 15 passes, raising his career total to 30, which tied the mark established by Terrell Buckley at Pascagoula High School. An All-State selection, Steve was named an All-American by Super Prep magazine.

Steve was recruited heavily by schools all over the southeast, including Florida State. But every major program wanted him as a defensive back. Steve considered himself a quarterback and refused to go to any college that didn’t share this view. That essentially narrowed his choice down to Alcorn State in Mississippi, where coach Cardell Jones recognized Steve for what he was: a once-in-a-lifetime prospect.

Steve was familiar with Alcorn State because Fred had played there. Located in Lorman (a two-hour drive from Mount Olive), the school—with a student body of 3,300—competed in football at the Division 1-AA level. Though the Braves didn’t attract much media attention, Steve felt comfortable with his decision. Above all, he relished the opportunity to pilot Jones’s wide-open, shotgun passing attack.

Steve got his shot at Alcorn State’s starting job midway through the first quarter of the team’s opener in 1991. With the offense looking sluggish against Grambling, Jones turned to the freshman, who sparkled in a 27-22 victory. Steve went on to have a marvelous year. What he couldn’t accomplish through the air. he achieved on the ground, combining for a total of 3,199 running and passing yards—good for fourth in Division 1-AA. The Braves, meanwhile, exceeded all preseason expectations with a record of 7–2–1.

ON THE RISE

Steve’s breakthrough campaign helped raise Alcorn State’s profile in the Southwestern Athletic Conference. Though it had been eight years since the school’s last league title, the Braves were beginning to get noticed by national publications. And of course, every time the Braves were mentioned, Steve was the focal point of the story.

He lived up to his press clippings in 1992, throwing for 3,541 yards and 29 touchdowns, and running for 10 more scores. The Braves fashioned a record of 7–4, including a last-second victory in their rematch with Grambling. In that contest, Steve returned from a severely sprained ankle to ignite a dramatic comeback. With Alcorn State trailing late in the final period, he moved the team deep into Tigers’ territory. Then, despite limping badly, he tucked the ball under his arm and dove into the end zone for the winning touchdown. The victory over Grambling helped the Braves qualify for the 1-AA playoffs, where they were blitzed by powerful Northeast Louisiana, 78-27.

Heading into his junior season, Steve was beginning to attract the interest of national reporters. Sports Illustrated, The Sporting News and The New York Times all ran feature stories on him. NFL scouts were intrigued by his combination of skills, too. Steve—by this time dubbed “Air McNair”—was big and strong, could run faster than most running backs and receivers, and had a cannon for an arm.

Some wondered, however, whether the pro game might be too complex for him. Steve was facing unsophisticated defenses almost every game, and he always had the out of running if he didn’t spot a receiver in the clear. In the NFL, by contrast, every down was like solving a math problem. Those who claimed Steve’s resume did not add up to a pro career reopened a debate that had been troubling football for more than two decades: Was there a bias against black quarterbacks?

To his credit, Steve chose not to enter into the conversation. As far as the issue of race was concerned, he saw no benefit in addressing a point that players like Doug Williams and Warren Moon had already put to bed. He also brushed aside questions regarding his “football IQ.” A good student since his days at Mount Olive, he was confident he could handle the intricacies of the NFL. At Alcorn State, Steve worked hard in the classroom and boasted a solid B average. In fact, getting his diploma was a matter of great pride. Because Fred had left Alcorn State before graduating, Steve stood to be the first in his family to earn a college degree.

Steve guided Alcorn State to another good year in 1993, as the Braves upped their record to 8-3. Despite defenses designed to stop him, he racked up more than 3,000 yards through the air and a total of 30 touchdowns. Named First-Team All-SWAC for the third year in a row, Steve propelled himself squarely into the national spotlight. But the season wasn’t all smiles for him. Unfortunately, he played through a good part of it with a heavy heart after learning that Grandma Hattie passed away.

The pressure on Steve in his final college campaign was unlike anything he had ever experienced. Despite playing Division 1-AA, Alcorn State was ranked in the Top 20 by some preseason polls, and he was a legitimate candidate for the Heisman Trophy. On top of that, his status in the NFL draft—and millions of dollars—seemed to be at stake each time he took the field.

The first game of the year ended in a 62-56 defeat at the hands of Grambling. But as losses go, it was not a terrible one. With the Tigers rolling up the points, Steve was forced to go for broke on almost every possession. In the process, he threw for 485 yards and five touchdowns. On the game’s final play, he lofted a perfect pass to Percy Singleton, who dropped the ball for what should have been the tying score.

The following week, against Tennessee-Chattanooga, Steve made headlines again. This time he amassed 647 total yards—the most ever in a Division 1-AA game—and passed for eight touchdowns. Not only did the performance raise eyebrows among Heisman voters, it also put Steve on pace to eclipse Ty Detmer’s record of 15,049 career yards.

Steve continued to gobble up yards as the season progressed. Against Southern University, he surpassed his own single-game mark with 649 yards. In the playoffs against Youngstown State, he completed a record 52 passes. When it was all said and done, Steve had gained nearly 6,000 yards rushing and passing, along with an amazing 53 touchdowns. In the process, he surpassed more than a dozen records (including Detmer’s). Named an All-American, Steve won the Walter Payton Award and finished third in the Heisman voting behind Rashaan Salaam and Ki-Jana Carter.

The Senior Bowl was Steve’s first stop on his way to the pros. He used the game to showcase his skills as a drop-back passer, demonstrating that he could do more than scramble from a shotgun formation. Next he wowed scouts at the NFL Combine in Indianapolis. Steve also revealed a thoughtful and intelligent side that coaches loved.

Among those impressed were the Houston Oilers, owners of the third pick in the draft. The team had won just twice in ‘94, a woeful record that cost coach Jack Pardee his job. Jeff Fisher, a former defensive back with the Chicago Bears, was hired to replace him and remained the head man going into 1995. At the top of his wish list was a big-time quarterback.

After Carter and Tony Boselli went with the first two picks, the Oilers selected Steve. They quickly signed him to a seven-year contract worth $28 million. The first thing the 22-year-old did with his money was build his mom a new house in Mount Olive. She broke down in tears when he showed her the plot of land. It was the same place she had picked cotton as a girl.

During training camp, Steve tried to absorb as much about the pro game as he could. He also weathered Houston’s hazing rituals, including wrestling a pig in a mud pit. Every one of Steve’s teammates grinned at how easily he handled the task.

Going into the ’95 season, Fisher told Steve that he would not become the starter until the team felt he was ready. Owner Bud Adams had dismantled the Oilers over the summer, and the coach saw no reason to rush along his rookie. Besides, with Chris Chandler in camp, Houston had a veteran calling the signals. Steve spent the year working with quarterback guru Jerry Rhome, whom the Oilers hired specifically to groom him. On the inactive list for half of the season, Steve didn’t see his first action until the last two series of the fourth quarter in a November game versus the Browns in Cleveland. Late in the season, he also appeared briefly against the Detroit Lions and New York Jets.

The Oilers, meanwhile, surprised many onlookers by holding their own with a record of 7-9. Chandler enjoyed a fine year, finishing as the AFC’s fourth-best passer, while Fisher molded the defense—led by linebackers Al Smith and Michael Barrow and an excellent secondary featuring Blaine Bishop and Darryll Lewis—into one of the league’s most improved units.

Expectations were mixed for 1996. The defense figured to be strong again with the linebacking corps and secondary remaining in tact. In addition, rookie tackle Bryant Mix, a former teammate of Steve’s at Alcorn State, helped shore up the front four. The offense, by contrast, had yet to find its identity. Ohio State running back Eddie George, the Oilers’ first-round draft choice, figured to be an impact player as soon as the offensive line gelled. Until then, the team decided it would stick with the experienced Chandler, leaving Steve once again to ride the bench.

This year would be different, however. Promoted to first back-up, Steve assumed more responsibility off the field, in practice and during games. Chandler could see the writing on the wall—he was just keeping a spot warm for Steve. Chandler barely spoke to the second-year quarterback and complained loudly that he was being taken for granted.

Houston’s coaching staff and players observed how adeptly Steve dealt with this sticky situation. Fisher began inserting him in games when his chances of success were greatest. Then, in December, Steve got the start against the Jacksonville Jaguars. Though the Oilers fell 23-17, he threw for more than 300 yards and managed the offense with tremendous poise. The performance helped convince Fisher that Steve was ready to be his #1 quarterback. Overall, Steve got into 10 games, passing for 1,197 yards and six touchdowns.

The Oilers ended the ’96 campaign at 8-8, including six wins on the road. The team’s problems at home stemmed from Adams’s plan to move the franchise to Tennessee. Fans in Houston reacted angrily, and the Astrodome turned into a haven for visiting squads.

Fod Stevem Fisher’s vote of confidence in him bolstered his spirits. So did his June marriage to college sweetheart Mechelle Cartwright. More than 1,500 people attended the wedding, making it one of Mississippi’s biggest social events of the year.

Steve’s first season as a starter in 1997 produced another .500 record. Playing their home games at the Liberty Bowl in Memphis, the Oilers began the campaign slowly and finished the same way. For the first time under Fisher, the defense showed cracks, dropping to 22nd in the NFL. Though the team used its top draft choice on defensive end Kenny Holmes, it had trouble rushing the quarterback. As a result, the Oilers were victimized by opponents with good passing attacks. A tough stretch in late November also exacted a heavy price, as the club faced three games in 11 days. A 41-14 drubbing at the hands of the Cincinnati Bengals dashed any real hope of a playoff berth.

For Steve, the upside was his development into one of the league’s rising stars. His 2,665 passing yards were the most for the Oilers since Warren Moon in 1993, and his 13 interceptions were the fewest for a single season in franchise history. Steve was most dangerous when he looked to run. He led team in rushing touchdowns with eight and ranked second behind George with 674 yards on the ground, the third-highest total for a quarterback in NFL history.

In 1998, the Oilers officially changed their name to the Tennessee Titans and took important steps toward becoming an AFC powerhouse. Steve had an excellent year, setting career highs with 492 attempts, 289 completions, 3,228 yards and 15 touchdowns. He also cut his interceptions to 10, helping his quarterback rating climb to 80.1. With defenders back on their heels, Steve and George both had more room to run. The two combined for nearly 2,000 yards and nine touchdowns. As Fisher had hoped, the Titans were turning into a team built for postseason success. Though they lacked a big-play receiver, their offense controlled the ball with great effectiveness.

Tennessee’s pressing need remained an impact player on defense. Fisher’s system relied on power along the line and speed at linebacker and in the secondary. The team had plenty of the latter, thanks mostly to Bishop and free safety Marcus Robertson. Up front, however, the Titans again were unable to apply much pressure on enemy passers. This shortcoming didn’t hurt much in the AFC Central, where the team went 7-1. But outside the division, Tennessee won only once. In fact, losses to the Chicago Bears, San Diego Chargers and Seattle Seahawks—who had just 17 victories between them—sunk the Titans, who ended at 8–8.

Still, there was reason for optimism. The Titans had endured another year in a makeshift home, this time at Vanderbilt Stadium in Nashville. Construction on a state-of-the-art facility was under way, and a new fan base was growing in numbers.

MAKING HIS MARK

The Titans entered the 1999 campaign feeling like the postseason was within their reach. The offense was looking good with tackles Jon Runyan and Brad Hopkins emerging as stars, while free-agent blocking back Lorenzo Neal joined the lineup to boost the production of George. Speedster Yancey Thigpen, meanwhile, gave the team a solid deep threat. Steve spent the summer working on long-ball drills in anticipation of an excellent passing year.

The most important addition to the team was Jevon Kearse, taken with the 16th pick in the draft. Along with second-round choice John Thornton, the “Freak” provided Tennessee’s defensive line with energy and athleticism. The pair of rookies instantly transformed the club’s stagnant pass rush. With the rest of the unit unchanged, Fisher hoped for big things from his defense. The strategy heading into the season was to beat up opponents in the first half, keep games close, and then let Steve and George do their thing in the final 30 minutes.

Steve was fantastic in the season opener against the Bengals. In a 36-35 win, he completed 21 of 32 passes for 341 yards and three touchdowns, including a 47-yard bomb to Thigpen. Afterwards, however, the news was bad. In pain for most of the preseason, Steve was diagnosed with an inflamed disk and needed surgery. In his place stepped Neil O’Donnell, a veteran who had guided the Pittsburgh Steelers to the Super Bowl four years earlier. During the next five games, O’Donnell led the Titans to a 4–1 record.

Steve’s first game back found the Titans playing the surprise team of the year, the St. Louis Rams. Sharp as a tack, he threw a pair of touchdown passes and ran for a third score to give Tennessee a 21–0 lead. But the explosive Rams—who boasted the trio of Kurt Warner, Marshall Faulk and Isaac Bruce—clawed back and managed to set up the game-tying field goal. When Jeff Wilkens missed the kick, the Titans escaped with a 24-21 victory.

With Steve at the helm, Tennessee stormed to wins in seven of its last nine, good for a record of 13-3 and second place in the AFC Central. Kearse was magnificent, registering 14.5 sacks, while George ran for more than 1,300 yards. Steve, however, was the team’s heart and soul. Though his back still bothered him, his performance never suffered. Spreading the ball around—tight end Frank Wycheck topped the team with 69 receptions—Steve kept everyone on the offense happy and involved. While his numbers didn’t blow away anyone (2,179 yards and 12 TDs on 56.5% passing), he inspired his teammates with his rare brand of toughness. In addition to his disk problem, Steve played through a bad case of turf toe and bruised ribs.

Tennessee opened the playoffs at home against the Buffalo Bills in a Wild Card game. The Titans appeared to take control with a safety, a short touchdown run by Steve and a field goal by Al Del Greco. But the Bills roared back to go ahead 13–12. On a crucial third down late in the fourth quarter, Steve made a super run to set up another Del Greco field goal. Buffalo’s Rob Johnson responded with a scoring drive that seemed to put the game on ice. But on the ensuing kickoff, the Titans pulled off the now-famous “Music City Miracle,” scoring on a crazy lateral play to claim the most unlikely of victories.

Next up for Tennessee were the Colts in Indianapolis. Much to Fisher's delight, Steve executed the game plan perfectly. Though the Titans were down 9-6 at intermission, they were battering the Colts with their physical, ball-control offense. In the second half, George ran wild on the tired Indianapolis defense, and Tennessee held on for a 19-16 win.

One step away from the Super Bowl, the Titans travelled to Jacksonville for the AFC Championship Game. Steve, who had burned the Jags with five touchdown passes earlier in the year, felt confident. So did Fisher, who decided to turn his quarterback loose. Down 14-10 at the half, Tennessee started the third quarter looking to deliver a knockout blow. When Steve piloted the Titans to a touchdown on their first possession, the game was in the bag. Tennessee cruised 33-14 and advanced to the Super Bowl for the first time in franchise history.

Seeing through a winning strategy in their rematch with St. Louis was easier said than done. The Titans needed to pressure Warner and punish Faulk and the Ram receivers. Things didn’t go particularly well in the first half and only got worse in the third quarter, as St. Louis scored to go up 16–0.

That’s when Steve and the Titans started pecking away. George bulled in twice from in close, and then Del Greco kicked a 43-yarder to knot the score. With time ticking away, the Rams prepared to mount one last drive from deep in their own territory. Warner looked for Bruce on a pass play but rushed his throw with Kearse in his face. The agile receiver adjusted beautifully and grabbed the pass in stride. He split the Titan defense and pulled away for an incredible 73-yard touchdown.

The score came so quickly that Tennessee still had time left on the clock. Steve moved the Titans down the field with several short passes and a magnificent scramble. With time left for one play, he used the sure-handed Wycheck as a decoy and looked for receiver Kevin Dyson, who was angling toward the goal line. Steve drilled the pass to Dyson who turned to the goal line. But linebacker Mike Jones had not taken the bait and was able to pull him down a yard short of the end zone. In a game no one deserved to lose, the Rams celebrated a 23-16 victory. Warner—who threw for 414 yards—was named MVP. Steve finished the contest with a combined 278 yards and newfound respect from the whole football world.

Steve’s spirited effort in the Super Bowl helped earn him a new contract with the Titans, who inked him for six years at $47 million, including a two-tiered signing bonus of $16 million. Steve understood the implications of the deal. The Titans were betting that he could get the team back to the big game and win it all.

The club looked like it was on its way to doing just that after posting the AFC’s best record (13-3) in 2000. George racked up the most yards of his career, while fourth-year wideout Derrick Mason developed into a threat on the outside. The speedy receiver did double duty, also making his presence felt as a kick and punt returner. The defense, meanwhile, was the NFL’s most dominant unit. Kearse forced opponents to alter their blocking schemes, which opened the field for the rest of the Titans. In turn, defensive coordinator Gregg Williams was able to utilize a full package of blitzes, which produced 55 sacks. In the secondary, cornerback Samari Rolle rose to the ranks of the league’s best.

The Titans, however, were given a taste of their own medicine in the playoffs, when the Baltimore Ravens manhandled them 24-10 at Adelphia Coliseum. Steve was as much to blame as anyone. The Ravens crowded the line, daring him to beat them with his arm. Though he moved the ball between the 20’s, he couldn’t finish off drives.

Steve’s problems against Baltimore were a microcosm of his campaign. He started every game but one and posted the best quarterback rating of his career (83.2). He also ran the ball well, gaining more than 400 yards. But in the red zone, the Oilers often stalled. Opponents shadowed Steve with a “spy” to limit his running options. Enemy defenses also knew that Steve normally didn’t take chances throwing downfield. His leading receiver was again Wycheck, who caught most of his passes underneath the coverage.

Steve’s conservative approach was the result of two factors. Injuries certainly played a role. Early in the year, Steve suffered a severely bruised sternum that never really healed. He also logged most of the season with a sore right shoulder. After the campaign, in fact, he had surgery to repair the damage.

Steve’s ‘00 performance was also affected by Tennessee’s offensive philosophy. As long as he had been the starter, Fisher’s strategy called for him to manage games by handing off to George and avoiding mistakes. If he was going to change, the Titans had to open up their game plan, too.

That process had actually already begun, thanks to the teachings of offensive coordinator Mike Heimerdinger. Formerly an assistant with the Denver Broncos, he had joined the coaching staff after Tennessee’s Super Bowl loss. Heimerdinger worked closely with Steve. Heading into the 2001 campaign, the two were ready to overhaul the Titans’ attack. Their timetable was further pushed along because George had foot surgery in the offseason and was not completely healthy by the opener. Tennesse had no choice but to spread the offense and throw the ball downfield.

The club also found itself playing catch-up most weeks. Indeed, the defense suffered when Williams left to coach the Bills, while injuries and suspensions robbed the unit of several key contributors. Tennessee plummeted in every defensive category, including points allowed and turnover differential. The Titans finished tied for third in the newly formed AFC South at a disappointing 7-9, including five losses at home.

In the midst of all this misery, Steve reasserted himself as the team’s unquestioned leader. On opening day against the Dolphins, Miami’s Jermaine Haley buried him on a dubious hit, which reaggravated Steve’s right shoulder injury. He sat out the following game against Jacksonville, and then returned for a grudge match versus the Ravens. Though the Titans lost, Steve’s teammates marveled that he was even on the field.

From there, the 28-year-old put together his most productive year as a pro. With no running game to speak of, Steve registered career passing highs in yards (3,350), completions (264), touchdowns (21) and QB rating (90.2). He was also the team’s most effective rusher, tying George for the club lead with five scores. Named to the Pro Bowl for the first time, Steve did it all with a sore right shoulder and right thumb. The second injury happened in November and made it difficult for him to grip the ball. As usual, Steve fought through the pain and refused to come out of the lineup. After the season, he had another shoulder operation, which caused him to miss the trip to Hawaii.

Steve entered the 2002 season determined to lead the Titans back to the playoffs. After the first five games, however, the team appeared destined for another sub-par year. At 1-4, Tennessee was being outplayed in nearly every phase of the game. The defense was adjusting to several new faces, including rookie tackle Albert Haynesworth and free-agent safety Lance Schulters. Another change was the promotion of linebacker Keith Bulluck to the starting lineup.

On offense, Steve searched for support from someone other than Mason. George was getting plenty of carries, but his production didn’t necessarily justify all the work. While the Titans were putting points on the board, they weren’t firing on all cylinders.

Frustrated by his team’s lackluster performance, Fisher called a closed-door meeting and blasted his players. Steve responded by taking matters into his own hands. After guiding Tennessee to a win over the Jaguars, he claimed honors as AFC Player of the Week with a fourth-quarter comeback in a 30-24 victory over the Bengals. The Titans won their next three to push their record to 6-4.

Two weeks later, Steve authored a virtuoso performance in the swirling winds of the Meadowlands against the Giants. With Tennessee trailing in the fourth quarter, he rallied his troops to another dramatic win. On the day, he completed 30 of 43 passes for 334 yards and three touchdowns.

Riding the emotion of the victory over New York, Tennessee ran the table to go 11-5, good for the second-best mark in the AFC. To a man, the Titans credited Steve for their amazing turnaround. With the defense decimated by injuries, including large chunks of time missed by Kearse and linebacker Randall Godfrey, the team depended on its offense to carry the load. Steve thrived under the pressure. Despite his normal collection of painful bumps and bruises, he enjoyed the finest year of his career, with personal bests in nearly every significant offensive category.

The real story of Steve’s season was not told by the stats, however. During one five-week stretch, his body was so badly battered that he simply couldn't practice. Still, he gutted it out every Sunday, starting all 16 games. Before the postseason began, the Titans learned that Steve finished third in the MVP voting, behind Rich Gannon and Brett Favre. The news irritated his teammates, who felt their quarterback was penalized for having far fewer offensive weapons than the Oakland and Green Bay quarterbacks.

Tennessee opened the playoffs with a controversial 34-31 victory over the Steelers, as a penalty flag gave kicker Joe Nedney a second chance at a game-winning field goal. A week later. the Titans visited Oakland in the AFC Championship Game. With the high-powered Raiders lighting up the scoreboard, the onus again fell on Steve to deliver a victory. He got Tennessee to the fourth quarter down by three points, but the defense crumbled and the Titans lost 41-24.

Several months later, Steve found himself in unfamiliar territory. In May of 2003, he was arrested for DUI and illegal gun possession. His blood alcohol was above 0.10, and a 9-mm handgun had been sitting in the front of the car. Steve made no excuses for his lapse in judgment and issued a heartfelt public apology. His family, coaches, teammates and fans all forgave him.

Heading into the ‘03 season, McNair and the Titans were one of the favorites to represent the AFC in the Super Bowl. The roster was virtually the same from the year before. The question was whether several key players—Steve, George and Kearse most notably—could stay healthy. With Bulluck and Rolle playing like Pro Bowlers, Tennessee’s defense was re-emerging as one of the league’s hardest-hitting and most opportunistic units. The offense, meanwhile, had the potential to be explosive. Fisher’s ability to adjust his coaching strategy to fit his talent was a major advantage.

Early in the year, Steve established himself as a legitimate MVP candidate. Tennessee won nine of its first 11, and he was the primary reason why. Steve was putting up the kind of pass-happy stats he had produced during his career at Alcorn. In a 30-13 drubbing of the Steelers, he hit on 15 of 16 attempts, three of which went for touchdowns. He torched the Houston Texans for 421 yards and three more scores.

But Steve’s all-out style of play again caught up to him. In December, a gimpy calf and ankle kept him on the sidelines for two games. Still he finished with the best numbers of his career, including 24 touchdown passes and a QB rating of 100.4. The Titans ended at 12-4, the same record as the Colts, but Indy took the AFC South by virtue of its two victories over Tennessee. The MVP voters were duly impressed by Steve and Peyton Manning, deciding the two should share the award.

For Steve—who always placed the team before himself—the recognition was overwhelming. He was so emotional in his press conference that he was almost moved to tears. Some of his teammates were upset, only because they felt the MVP should have been Steve’s alone.

In the playoffs, the Titans first visited the Ravens in Baltimore. Steve was clearly hobbling, but the thought of not suiting up never crossed his mind. Though he threw three interceptions, his presence in the huddle was enough. Tennessee controlled the ball with a bruising running game and held on for a 20-17 win.

The team’s next foe was New England, in bitterly cold Massachusetts. The Patriots—winners of 12 straight to conclude the regular campaign—were well rested but also well aware of Tennessee’s talent and tenacity. Down 14-7 at the half, the Titans tied it up in the third quarter on an 11-yard pass from Steve to Mason. The Patriots grabbed the lead again with four minutes to go on a field goal by Adam Vinatieri. Though Steve drove Tennessee into New England territory with time winding down, his fourth-down desperation heave to Drew Bennett fell incomplete. The receiver actually had his hands on the ball but couldn’t haul it in. Afterwards, Steve was praised for his gutty effort. Of course, he would have settled for a win and the silent treatment from the media.

Steve and the Titans faced big expectations for 2004, even though they were weathering major roster changes. George left via free agency, opening the door for Chris Brown to become the team's feature back. Steve lost another weapon when receiver Justin McCareins was shipped to the New York Jets for a second-round draft choice. On defense, Kearse also hit the road, signing with the Philadelphia Eagles.

Steve and the Titans opened against the Dolphins with encouraging results. Brown rushed for 100 yards on 16 carries, and while Steve completed only nine passes, one went for a TD in the 17-7 victory.

After a pair of losses, Steve missed the season's fourth game with a bruised sternum, an injury suffered the previous week against Jacksonville. He returned with an excellent effort in a 48-27 blowout of the Packers, but then he played terribly in a home loss to Houston. In one of his worst games in recent memory, Steve was intercepted four times and fumbled once.

At 2-3, Tennessee was off to a slow start, but the blame wasn't all Steve's. The offensive line had yet to ge—he was getting pounded, including eight sacks in the first three contests of the year. When the Minnesota Vikings knocked him out in the first quarter of their October meeting, he reaggravated his sternum injury. Steve missed the next two games.

He didn't suit up again until November, when the Titans visited the Jaguars. With Tennessee languishing at 3-6, this was a make-or-break contest. Steve and his teammates responded with a gutty 18-15 victory. But they followed with a flat performance in Houston. Steve enjoyed his best day of the season (25 for 42 for 277 yards and 3 touchdowns) with nothing to show for it.

Afterwards, Steve reassessed his team's dwindling playoff hopes. Still ailing, he chose to end his campaign early. For the first time in his career, it seemed his perpetually poor health had raised serious concerns in his own mind. At one point, he even talked of retirement.

Without their leader, the Titans limped home. Billy Volek showed flashes of brilliance filling in for Steve, but Tennessee no longer scared opponents on either side of the the ball. Losers of four of their last five, they finished at 5-11. Steve's numbers—1,343 yards, nine total touchdowns and a 73.1 QB rating—were his lowest since 1996.

Late in December, Steve underwent an operation to correct the pain he felt during the 2004 season. The problem was that he had cartilage instead of bone in his sternum—an unusual condition for anyone, and certainly far from ideal for a pro football player. Doctors removed some bone from his hip and used it in his chest.

The operation was a success, and Steve was healthy enough to start 14 games in 2005. He was working at a disadvantage, however, as salary cap challenges ravaged Fisher’s defense. Steve managed to put plenty of points on the board, but the Titans won only one game in September, October, November and December, finishing 4–12. Steve passed for 3,161 yards and 16 touchdowns. So despite h’is teams poor recor, he was recognized with his third Pro Bowl selection.

Steve and the Titans decided to part ways after the season. They agreed that if his agent could engineer a fair trade, the team would take it. In June, a deal for a fourth-round draft pick was worked out with the Ravens, a club with a defense like the Titans of old. The franchise had lacked a first-rate quarterback and hoped Steve would be at least a short-term solution. He was that and quite a bit more. Steve played in every game in 2006 and led Baltimore to a 13–3 record, which was good for first place in the AFC North.

Steve completed 63 percent of his passes and topped 3,000 passing yards again. He made his fourth and final Pro Bowl. His dream season ended in the playoffs with a 15–6 defeat at the hands of the Super Bowl-bound Colts.

Steve logged his final NFL season in 2007. In an injury-riddled campaign, he missed 10 games due to back, shoulder and leg injuries. In Week 9 against the Steelers, James Harrison buried him again and again. Steve finally had to leave the game. He passed for only 1,113 yards on the year as the Ravens went 5–11, costing coach Brian Billick his job.

NFL defenses didn’t have McNair to kick around any more in 2008. He made a graceful exit from the game to which he had given so much. His retirement was short-lived, literally. On July 4, 2009, police found his body in a Nashville apartment, along with that of a woman, Saleh Kazemi, whom Steve had been dating for several months. Both had been shot through the head. An investigation was immediately launched, and Steve’s death was ruled a homicide.

Within days, police revealed that McNair was shot twice in the chest and twice in the

head while he was asleep. Kazemi had pulled the trigger and thenthen turned the gun on herself. She apparently suspected McNair of having another mistress and talked openly to friends about her plan to "end it all." McNair will be sorely missed by family, friends, and NFL fans everywhere.

STEVE THE PLAYER

Steve’s legs were his most important attribute. Not only was he a tremendous runner, he was also a load for oncoming pass rushers to bring down. He was most dangerous when he broke the pocket, as opposing defenses were almost helpless to stop him. If they pursued him too aggressively, he’d zip a pass to an open receiver. If they hung back in coverage, he’ld tuck the ball under his arm and take off.

Steve didn’t run as much late in his career, which was partly a function of the pounding he’s absorbed over the years. But it also demonstrated the evolution of his decision-making process. He realized that sometimes shedding a defender, throwing the ball away and surviving for another down with manageable yardage was the best play.

Accuracy had been a problem at times for Steve, despite his year-in, year-out 60+ passing percentage. Steve worked hard on his footwork to correct this flaw. He spent time every off-season on his drop-backs, creating rhythm and a smoother delivery. As any quarterback will attest, hitting receivers in stride has a lot to do with proper set-up.

Leadership was the area where Steve has made his reputation. In pressure situations, he was cool and confident. His willingness to play with pain was a constant source of inspiration to his teammates. In turn, there was nothing they wouldn’t do for him.

EXTRA

* Several of Steve’s teammates from Alcorn State also played in the NFL, including DE John Thierry, WR Cedric Tillman and WR Torrance Small.

* Steve’s older brother, Fred, played in the Canadian Football League, NFL Europe and the Arena Football League. He also starred at Alcorn State before Steve did. In fact, Fred was the first to be dubbed “Air McNair.”

* In 1997, Steve topped the NFL in yards per carry, edging Barry Sanders 6.7 to 6.1.

* Steve’s 64 yards rushing in Super Bowl XXXIV set a record for quarterbacks.

* Steve was named AFC Player of the Month for his performance in December of 2002. In leading the Titans to five wins, he threw just one interception in 133 passing attempts.

* Steve posted a perfect quarterback rating (158.3) for a half three times in his career—against the Pittsburgh Steelers and Cleveland Browns in 2001 and the Houston Oilers in 2003.

* Steve completed 60 percent or more of his passes each season from 2000 to 2006. His 63 percent mark in 2006 was the highest in Ravens’ history,

* In his first year with Baltimore, Steve set a franchise record with an 87-yard touchdown pass to Mark Clayton.

* Steve was one of only five quarterbacks in NFL history to rush for 3,000 yards and throw for 20,000 yards. The others are Fran Tarkenton, John Elway, Randall Cunningham and Steve Young.

* Steve’s back was so bad that he couldn’t sit longer than 15 minutes without it stiffening up. He would have to get up from his seat four times an hour whenever he flew.

* Steve ran a football camp for 300+ kids every summer.

* Steve and Mechelle had four sons—Steve Jr., Steven, Tyler, and Trenton. They lived on a 647-acre farm in Mississippi.

* Mechelle, who earned a degree in Biology from Alcorn State, also has a nursing degree from Belmont University in Nashville. In 2001, when Steve developed an infection after shoulder surgery, she was the one who administered his IV’s.

* Steve spent part of every offseason fishing with Brett Favre, also a native of Mississippi.