Spec Sanders biography

Date of birth : 1918-01-26

Date of death : 2003-07-06

Birthplace : Temple, Oklahoma, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-23

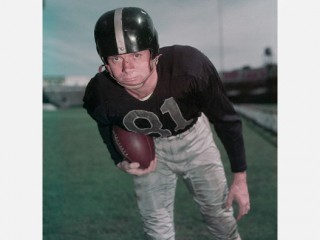

Credited as : Football player NFL, played for the New York Yankees , Super Bowl winning

0 votes so far

Spec loved sports, especially football. When he wasn’t playing against other boys, he practiced endless hours on his own, throwing footballs at targets, punting for distance and dodging imaginary tacklers.

By the seventh grade, Spec was good enough to make the high school team in Temple. He had to wait two years before he was eligible, and then immediately made the varsity. Spec was a football coach’s dream. He was smart, polite, big, fast, and determined. An outstanding student. Spec worked in a local clothing store to make extra cash. Later, he worked in a lumber yard.

In 1936, Spec transferred out of Temple High and made arrangements to complete his education at Cameron Junior College in the nearby town of Lawton. Cameron offered high school-level courses, and the team’s football coach saw this as a way to snag Spec two years before the big colleges got him. By the rules of the day, Spec was eligible to play four years of JC ball, which he did.

Spec transformed Cameron into a regional powerhouse. In 1940, after receiving his high school diploma and two years of college credits, he accepted a scholarship from Dana X. Bible at the University of Texas.

Spec was scouted at Cameron by Longhorns assistant Blair Cherry, who heard stories from Texas alumni about a bruising inside runner in Lawton. As a rule, UT did not cross state lines to recruit, but Bible and his staff kept getting letters about Spec. They knew that two of their chief rivals—Southern Methodist and Oklahoma—were trying to sign him. The Longhorns had lost to both of these teams in 1939 and did not want to see Spec beating them in another uniform in 1940.

Texas had a young and hungry team led by talented underclassmen Jack Crain, Mal Kutner and Pete Layden. Crain and Layden were backfield stars of national renown, and Spec would play his junior and senior seasons in their shadows. Bible used his newest runner to blow open games in short bursts.

The Longhorns went 8–2 in Spec's first campaign. Their season included a shutout of mighty Texas A&M that would kill the Aggies’ chances of playing in the Rose Bowl that January. Spec didn’t take the field in the A&M game. He was injured much of the year and did not play in several contests. He had a total of six carries, two catches, two punts and three punt returns.

Texas was so deep in 1941 that Spec ended up as a member of Bible’s second unit once again. Originally, the Longhorns had thought of Spec as a pile-driving fullback. They soon realized he was best in the open field. But as long as Crain was on the squad, Spec would be his backup. They were considered the two best runners in the Southwest Conference. Spec rushed for 365 yards, the sixth best mark in the conference. He averaged almost eight yards per carry and scored 53 points.

Spec stood an even six feet tall and weighed around 190. He always looked like he was running downhill. Even on the most savage tackles, he managed to fall forward for an extra yard or two. Despite being a second stringer behind Crain, Spec actually received some mention on a couple of All-America squads.

Spec’s best game as a collegian came against the rival Aggies. The Longhorns hadn’t won on Texas A&M’s home field since the 1920s. Spec set up the team’s first field goal with a 51-yard run. Later he gained 41 of 47 yards on Texas’s final touchdown drive in a 23–0 shutout.

The Longhorns finished the 1941 campaign at 8–1–1, tied for second in the SWC. They were ranked fourth in the country headed into their final game, but had not secured a bowl bid. Texas proceeded to batter Oregon 71–7. The euphoria did not last long. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor erased all thoughts of football that winter.

The war would take several of Spec’s teammates. Roy Weiss, Mike Sweeney and Chad Daniels died when their bombers crashed; Daniels had been the school’s first First-Team All-American in ’41.

The 1942 NFL draft yielded some great players. Do-everything back Bill Dudley was taken by the Pittsburgh Steelers with the top pick. Five selections later, the Washington Redskins called Spec’s name. A backup chosen in the first round? Spec made such an impact when he played for the Longhorns that he was roundly hailed as Texas’s “All-American substitute.” Still, it took a special scouting trip by the ’Skins before they were convinced. Washington coach Ray Flaherty dispatched a trusted scout to check on Spec. The scout—a young man named Bear Bryant—came back raving.

Others taken in the 1942 draft included Frankie Albert, Vince Banonis, Al Blozis, Tommy Prothro, Mac Speedie. Fellow Longhorns Layden and Kutner went to the New York Giants and Pittsburgh, respectively.

The war would cut into all of their careers in some way. Blozis, who quickly established himself as the top lineman in the NFL, was killed in a firefight in France. As for Spec, like a lot of top athletes, he was assigned to a training facility after enlisting in the Navy in 1942. He reported to Georgia Preflight in Athens, where he continued to play football. In 1943, Spec served in the Pacific. A year later, he was back in the states at North Carolina Preflight. He continued to play ball, sometimes against other former college stars, sometimes not.

After being discharged in 1945, Spec finished up the remaining credits he needed to receive his college degree in physical education. Texas coaches saw him on campus and fantasized about what their backfield would look like if he suited up next to Bobby Layne. Spec and his wife (they were married during his first stint in Austin) planned to settle in Stillwater, Oklahoma. However, football would come calling again.

The end of the war brought pro football back into focus for American sports fans. Besides the usual crop of talented young college grads, a wave of battle-hardened former stars was returning from service. There was enough talent for a second major league. In 1946, the All-America Football Conference was formed.

Though still largely unknown to football fans, Spec was among the players targeted by the new league. He was offered a healthy contract by baseball executive Dan Topping, whose New York Yankees had launched an AAFC entry of the same name. New York's coach, Ray Flaherty, remembered Spec from his pre-war days and urged Topping to sign him. Spec drew immediate respect from his teammates. The rangy back oozed talent. He was polite and serious—a natural leader.

Of course, Spec had his feisty side. In an exhibition game against the Los Angeles Dons, he faded back to pass and was sacked by Lee Artoe. The burly, battle-scarred Artoe took his time getting off the fair-haired Spec. As he rose, he pushed himself up off of Spec’s face. Artoe suddenly let out a shriek. Spec had chomped down on his hand. Next, Spec tore off two long runs totaling 55 yards. He later passed for a pair of touchdowns in the game.

The Dons were dumb enough to test Spec again during the regular season—this after he had embarrassed them with a 103-yard kickoff return. They gave him the works on several plays, only to emerge more battered than their target. Word soon spread around the AAFC that the good-natured Spec was not to be trifled with.

Under Flaherty, the Yankees ran the old single-wing offense. It would soon disappear from pro football thanks to the modern T formation. In the late 1940s, however, there were enough young “triple-threat” backs like Spec who could make it work. And that is just what he turned out to be. Running, passing, and kicking, Spec turned the Yankees into a formidable team. Flaherty compared his new star to Cliff Battles, one of the NFL’s top runners of the 1930s. Both were six-footers who could turn on an extra burst of speed at just the right moment for long gains.

The Yankees were actually a reconstituted version of the NFL’s old Brooklyn Tigers. Topping had fielded this squad (also known as the Dodgers) during the 1940s and lost a ton of money. In 1945, the Tigers had to merge rosters with the Boston Yanks to survive. The 1946 Yankees featured some holdovers from the Brooklyn/Boston team, including fading stars Ace Parker, Pug Manders, Bob Masterson and Bruiser Kinard.

Frank Sinkwich, a huge college star in the 1940s, was slated to run the New York offense, but a knee injury kept him out of action much of the year. Instead, the 34-year-old Parker stepped into the void. He was the NFL’s accidental Hall of Famer. All along he had eyed a major league baseball career. In 1937, Parker had hammered a home run in his first at bat with the Philadelphia A’s. Connie Mack gave him permission to play pro football after that season, and Parker became an instant star with the NFL Dodgers. He wasn’t great at any one part of the game, but he was very good at everything. In 1940, Parker was named NFL MVP. He quit baseball and made a decent living on the gridiron, guiding the Brooklyn team to within a victory of the Eastern crown in 1940 and 1941.

With the crafty Parker running the offense, Spec became New York's main weapon. In 14 games, he carried the ball a league-high 140 times and led the AAFC in rushing with 709 yards and rushing touchdowns with six. Spec also completed 33 passes for four touchdowns and averaged 15 yards per catch on 17 receptions, scoring three more TDs. Spec handled much of the Yankees’ punting, booting the ball 33 times for an average of 36.6 yards. One punt traveled 84 yards. He was New York’s main punt and kick returner, too, amassing another 652 yards and two touchdowns in these roles. On defense, Spec tackled hard and picked off two passes from his position at defensive back.

Spec used long strides to glide past tacklers. He was deceptively fast and during his prime years, he could change directions with lightning speed—much like Gale Sayers a generation later.

The Yankees easily won the AAFC East with a 10–3–1 record. Their only challenges came from the West. The mighty Cleveland Browns defeated them twice, limiting the Yankees to just one touchdown. The Chicago Rockets—led by their own two-way star, Crazy Legs Hirsch—dealt them their only other loss, as well as an early season tie.

The Yankees were prohibitive underdogs in the first AAFC Championship game, played in Cleveland three days before Christmas. However, coach Flaherty was no dope. He and his veteran players had learned a thing or two about Otto Graham and the Browns during their two losses. In the opening quarter, Eddie Prokop picked off a Graham pass, and Parker led an impressive drive back down the field that featured a long pass to Jack Russell and a first-down gallop by Spec. The resulting nine-yard field goal by Harvey Johnson put the Yankees on the scoreboard first.

Later in the opening quarter, the Browns had a first down on the 6-yard line, but New York kept them pout of the end zone and took over on downs. Cleveland tried a field goal in the second quarter, but Lou Groza’s kick went wide. The Browns finally scored before halftime, when Marion Motley barreled across the goal line following a series of Graham passes.

Not to be denied, the Yankees mounted a third-quarter drive from their own 20 that Spec finished off with a touchdown plunge from two yards out. The Browns blocked the extra point to keep the score a manageable 9–7. Still, they could not solve the New York defense as time ticked away.

Finally, with less than five minutes left in the fourth quarter, Cleveland put together an 11-play drive culminating in a 16-yard TD pass from Graham to Dante Lavelli. With the Yankees now forced to score, the Cleveland defense proved too much. Parker moved New York across midfield, but Graham stepped in front of a pass and made the interception. The Browns secured a 14–9 victory and the inaugural AAFC crown. Parker's errant pass was the final play of his career.

Though exhausted from a long season, Spec had run the ball 14 times for 55 yards—not bad numbers against Cleveland’s formidable front line. He also punted once for 45 yards and threw two incomplete passes.

The 1947 Yankees were favored to win the AAFC East again. The club had an excellent line in front of Spec, who now became New York’s backfield general. The loss of Parker was more than made up for by scatback Buddy Young, a 5’ 5” ball of energy who required the constant attention of the defense.

To Flaherty’s delight, Spec came to camp that summer a different player. He had spent the off-season back home in Oklahoma practicing in a plowed field. Leaping from furrow to furrow, he improved his lateral movement while running at full speed. He also shaved a step off his punting. And he threw countless passes at empty barrels, strengthening the only weak part of his game.

The Yankees improved to 11–2–1, beating the Buffalo Bills in the next-to-last game to sew up the division title. The Browns are remembered as the league’s glamour team, but the New York–LA sports rivalry was established in the AAFC, as witnessed by the 82,675 fans who watched the Yankees and Dons play in Week 3. Spec returned a kickoff 98 yards for a touchdown to open the scoring and threw three TD passes in a 30–14 win.

This was the rule for Spec’s performances in 1947, not the exception. He had one of the finest all-around seasons in pro football history. Game after game, he ran, passed, and punted the Yankees to victory.

Spec led the NFL with 231 carries, 114 points, and 18 rushing touchdowns, a new pro record that stood until Jim Taylor broke it in 1962. Spec’s 1,432 rushing yards established a mark until 1958, when Jim Brown ran for 1,527 yards. Spec completed 93 passes for 1,442 yards, adding 14 more touchdowns to the team’s total. He also returned a kickoff for a score. Although he was used sparingly on defense, Spec intercepted three passes. He also averaged 42.1 yards on 46 punts.

Spec’s greatest game that year came on a Friday night in October against the Rockets. He carried the ball 24 times and gained 250 yards to set a pro record that wasn't touched for more than 25 years. Spec was pulled from the contest after three quarters, replaced by John Sylvester—who gained 66 yards against Chicago.

For the Yankees, the 1947 campaign was a case of a great player, with a great team surrounding him, letting it all hang out on every play. Young, who gained over 1,000 yards running and receiving on the season, froze defenses on virtually every play. His fakes into the line bought Spec the extra second he needed to turn short gains into breakaway yardage.

After dropping their opener to the Bills, the Yankees won four straight before losing to the Browns in Yankee Stadium. A rematch in Cleveland saw New York build a 28–0 lead—only to have Graham lead a comeback to make the final score 28–28. The Yankees won every other game they played.

The Yankees and Browns met in the Bronx for the AAFC Championship. More than 60,000 fans turned out to see if Spec and his teammates could break Cleveland’s spell over their club. Unlike the regular-season meetings, the game was a defensive battle. Motley made the key play in the first half, breaking loose on a 51-yard run that led to a Browns’ touchdown. The Yankees came right back, with Spec punching through for healthy gains. But the drive stalled at the Cleveland 5-yard line, and New York had to settle for a field goal to make the score 7–3. That was it for scoring in the first half.

Unfortunately for New York, that was also all the team could muster for the day. The Browns added a third-quarter touchdown after intercepting a jump-pass by Spec, and the game ended 14–3 with the Yankees on the short end once again. New York did not go quietly, however. Twice in the final stanza, Spec drove the team into Cleveland territory. The first drive was killed by a fumble, the second by an unnecessary roughness penalty on Harmon Rowe, who took a swing at a Cleveland player after a first-down run by Young to the Browns’ 23. Spec, running on a sore ankle, ended the afternoon with 40 yards on 12 carries, and seven of 17 passing for 89 yards.

The 1948 Yankees were once again favored to win the East. Spec was joined in the backfield by former Texas teammate Pete Layden, who had been playing pro baseball. The New York offense sputtered early in the year, despite the addition of a brilliant young blocker named Arnie Weinmeister. The Yankees dropped six of their first eight games. Flaherty was replaced by Red Strader after a 35–7 loss to the Browns.

The coaching change perked up the club a bit. The Yankees won three in a row before dropping two of their final three. Despite their lackluster 6–8 record, they finished just one game out of first place, which was decided by a playoff between the Bills and Baltimore Colts.

Spec’s final numbers were impressive, but hardly approached the previous year’s totals. He ran for 759 yards, threw for 918 yards and accounted for 14 touchdowns on the ground and in the air. He also handled most of the team’s punting until a knee injury limited his time on the field.

In June of 1949, as training camp neared, Spec was in rough shape. His knee ached and showed little improvement despite off-season surgery. He announced his retirement, leaving the Yankees without a capable passer. Despite playing in only three seasons, Spec would go down as the AAFC’s all-time leader in rushing touchdowns, second in rushing yards, fourth in overall scoring and eighth in passing yards.

Given his prodigious exploits, Spec never got much ink outside of the New York papers. He was a nice guy and pleasant to reporters, but he was not exactly a quote-machine. Of course, at a salary more than $25,000 a year, he didn’t have much to complain about.

That summer, the Yankees merged with the Brooklyn club and found added talent and depth. New York still could not fill Spec’s shoes. The team finished third in the now single-division AAFC, one victory short of facing the Browns in the league’s final championship game. The AAFC folded after the season, with the Browns, 49ers and Colts joining the senior circuit.

As the 1950 season approached, Spec was getting the hang of the sporting goods business back home in Oklahoma. One day, he received a call from Strader, who had been hired to coach the NFL’s New York Yanks. The team had been named the New York Bulldogs in 1949. Before that, it had played in Boston.

Strader planned to cut all but a handful of the returning players and wanted to stock his roster with as many AAFC players as he could get his hands on. Spec doubted his knee would hold up to the grind of regular action on offense, so the two agreed that he would be limited to action in New York’s defensive backfield.

Strader's AAFC talent infusion turned out to be a wise decision. Former Bills QB George Ratterman joined the Yanks and threw for more than 2,000 yards, plus an NFL-best 22 touchdowns. Buddy Young was dynamite on kick returns and out of the backfield. And Spec provided the Yanks with a last line of defense that enabled them to finish with a very respectable 7–5 record.

As he had always done, Spec played every down as if it were his last. A master at reading pass plays, he was as close to a shut-down DB as there was in the NFL of 1950. Spec finished the year with 13 interceptions to tie the league record. In turn, he held or shared the single-season pro marks for rushing yardage, rushing touchdowns and interceptions, and the single-game rushing record. At the age of 33, he decided to go out on top and retire from football once and for all.

After the NFL absorbed the AAFC, the powers that be decided that none of the former league's records would count in the NFL record books. Suddenly, Spec's career was shaved down significantly. Unofficially, he played four seasons, rushed for 2,900 yards and 33 touchdowns in 40 games as an offensive back, and threw for 2,771 yards and another 23 touchdowns. Spec was credited with 240 points. On defense, he intercepted 19 passes.

Spec returned to Oklahoma and lived a quiet life as a small-town businessman. Within a couple of seasons, the teams for which he starred blinked out of existence and out of memory. His AAFC stats expunged and his exploits forgotten, Spec held out little hope that a call from Canton was forthcoming. By the time he died at age 85, he was known only to AAFC aficionados, along with the odd fan who stumbled upon his stats in a record book and dismissed them as a misprint.

Buddy Young, who saw a lot of football as a player and later a league official, once described Spec as being in a class with just a handful of other backs, including Jim Brown, Gale Sayers, Hugh McIlhenney and Lenny Moore. According to Young, his former teammate was “tough as nails."

“He took a tremendous beating every game and he was a mass of bruises from his hips down,” added Young.

Crazy Legs Hirsch was also an admirer of Spec’s. “Spec Sanders was one of those big backs who ran extremely hard,” he once observed. Hirsch recalled that his AAFC peers suspected Spec would burn out after a couple of seasons. They were right. But few players ever burned as bright.