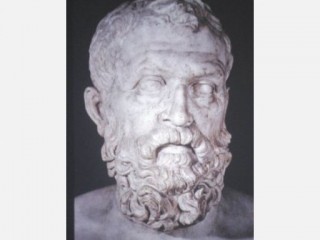

Solon biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Athens, Greece

Nationality : Greek

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-09-09

Credited as : Politician and statesman, poet, formulated an influential code of laws

13 votes so far

Sidelights

The future Athenian lawgiver Solon was born into a noble but impoverished family called the Medontids who claimed descent from Codrus, the last king of Athens. According to legend, Codrus had sacrificed himself to save the city from Dorian invaders some 500 years before. Solon's mother, whose name has been lost to history, was a cousin of the mother of the future tyrant, Pisistratus. His father Execestides had reportedly lost the family fortune as a result of his generosity to friends. But Solon became a successful merchant, living comfortably on his own income. By the time he came to a position of prominence in government, Solon could understand and sympathize with all levels of the Athenian citizenry.

Also admired as a poet, Solon left the best profile of himself in his poetry, some of which was quoted at length by later authors. The verses that are extant are political in nature, but it was said that in his younger days he wrote less didactic works, such as love poetry, as well.

During Solon's childhood, Athens experienced severe political turmoil as the Athenian nobleman Cylon seized the Acropolis in an attempt to make himself tyrant of Athens. Having married the daughter of Theagenes, tyrant of the neighboring city of Megara, Cylon had Megarian help in this unsuccessful coup. Although Cylon managed to escape from the city, his followers were not so fortunate and were executed despite a promise to spare them. This incident of civic violence was only symptomatic of a deeper conflict between the Eupatrids, a group of aristocratic families who controlled the government, and the rest of Athens's citizens.

The dissatisfaction of the middle class with the self-serving administration of justice by the Eupatrids led to the appointment of Draco (Dracon) as a special legislator with the duty of writing a new law code for the city. His laws were very strict--even minor crimes such as stealing cabbage were punishable by death--leading the later orator Demades to remark that Draco's laws "were written not in ink, but in blood."

When the Megarians captured the Athenian island of Salamis (which is closer to Megara than to Athens) around 600 b.c., Solon used his poetry to urge fellow citizens to "go to Salamis and fight . . . and wipe away our shame." Heeding his own advice, he served as general in the war that recovered Salamis. It was said that his kinsman Pisistratus served with him in the campaign; if that is true, the future tyrant was then very young. Tradition also connects Solon with the Athenian participation in the First Sacred War, fought in defense of free travel to the oracle of Apollo at Delphi.

The beginning of the sixth century b.c. saw the land of Attica, the home territory of Athens, in both economic and political distress. The aristocratic government had failed to meet the needs of the people in a time of economic, military, and social change, leading to conflict between poor and rich. Many poorer citizens had been reduced to a form of serfdom as tenant farmers called hektemoroi, who had to give their landowners one sixth of their produce each year. Many of the common people fell deeply into debt. Since their persons were security for loans from their patrons, they were sold into slavery to pay off a portion of their indebtedness. Before that happened, some of them first sold their children into slavery. Thus divided into hostile camps, the city was on the brink of revolution.

Solon Begins Year of Sweeping Reforms

This was the landscape into which Solon stepped as Nomothetes, or lawgiver. As Plutarch wrote, "The most level-headed of the Athenians began to look toward Solon," who was asked to adjudicate between the two bitterly divided sides. Since the end of the monarchy, nine archons ("leaders")--elected annually and ineligible to succeed themselves--were part of Athens's government. The most important of these was the Eponymous Archon, the civil executive head of government, after whom the year was named; this was the post to which Solon was elected in 594 b.c. The other archons included the Archon Basileus, or "king," whose functions were mostly religious and who had no royal power; the Polemarch, or war leader, a military commander; and six Thesmothetae, or law keepers, who served as judicial officials. While Solon's task of reorganizing the city and drafting a new law code was unique and not part of the ordinary duties of the Eponymous Archon, he avoided tyranny. Plutarch tells us, "He was concerned above all with applying morals to politics."

Solon's reforms were sweeping, affecting most areas of the city's life, but they may be divided into three classes: economic measures, political reforms, and miscellaneous enactments. Among his economic measures was a debt cancellation called the seisachtheia, or the "shaking off of burdens." This measure applied to loans made with land as security and provided that small farmers would no longer lose their land to rich creditors. The inscribed stones called horoi, previously placed on the land to indicate that the land was mortgaged, were uprooted as a sign of this new freedom. One of Solon's poems celebrated that act:

I call to witness at the judgment seat of time one who is noblest, mother of Olympian divinities, and greatest of them all, Black Earth. I took away the mortgage stones stuck in her breast, and she, who went a slave before, is now set free.

In addition, Solon outlawed debts with persons as security, effectively abolishing debt slavery. He also sent out agents to recover Athenians who had been sold into slavery elsewhere, asserting, "Into this sacred land, our Athens, I brought back a throng of those who had been sold, some by due law, though others wrongly; . . . These I set free."

Solon encouraged and regulated trade and production. He standardized the measures of weight and volume. Athenian coinage was revalued from a mina worth 70 drachmas to one worth 100 drachmas. This meant a change from the coinage standard of the Dorian island of Aegina, a rival of Athens, to the standard of Euboea, an Ionian ally and trade partner. Particularly important was a law mandating that only olive oil, and no other agricultural crops, could be exported. This measure was intended to keep valuable food grains at home and to encourage trade in Attica's most plentiful agricultural surplus product. Solon encouraged manufacturing, including the pottery industry that produced the ceramic ware in which the olive oil was shipped. To protect domestic animals, bounties were set on predators: for example, five drachmas were paid for a wolf (other sources indicate that a wolf-killer had to provide for the honorable burial of the animal). To expand irrigation and horticulture, he regulated the digging of wells and urged the planting of trees, especially olive trees. Evidently, the results of these measures were positive, as Athens would grow and prosper in the century after Solon.

Realizing "how many evils a city suffers from Bad Government and how Good Government displays all neatness and order," Solon enacted many political reforms as well. His legislation repealed the capital punishment set by the Draconian laws, except in cases of murder. The old family-based tribes (called Hoplites, Ergadeis, Gelontes, and Aigikoreis), whose structure had supported the previous aristocratic government of the Eupatrids, were supplemented by four classes based on wealth, thus allowing greater participation in government by the affluent middle class and, to a certain extent, making social mobility possible. The new classes were: the Pentacosiomedimni, or "Five-Hundred-Bushel Men," composed of citizens with an annual income equivalent to at least 500 measures of grain; the Hippeis, or "Knights," with an income worth between 300 and 500 bushels, who could presumably afford to keep horses; the Zeugitai, or "Teamsters," with income between 200 and 300 bushels, who could afford a yoke of oxen; and finally the laboring class called Thetes, with income under 200 bushels, which included those with no property at all. This reorganization opened governmental positions to wealthy citizens, rather than just the Eupatrids. The thetes were given the privileges of attending the Ecclesia ("Assembly") and sitting on juries but were not otherwise permitted to hold office.

The constitutional structure of government was altered. Solon created a Council of Four Hundred which took over some of the functions of an older aristocratic council called the Areopagus. The new council was composed of 100 members from each of the four tribes and had the duty of preparing the agenda for discussion in the Ecclesia. Archons and other magistrates were to be chosen by lot ("a chance drawing of names") from candidates selected by the four tribes. While using a lottery to select public officials may seem strange today, it was then considered democratic, since it gave each candidate an equal chance to serve; election with voting by name, on the other hand, was believed to favor the rich. Another provision that might appear odd by today's standards required every citizen to take sides in a time of civil strife. The ancient Athenians did not believe that citizens who tried to be non-political were "minding their own business," but were avoiding their public responsibilities. Solon also allowed naturalization of foreigners who came to Athens to live and to carry on a trade, a provision that would encourage the economic growth of Athens as well as broaden the political base.

Finally, Solon's miscellaneous enactments included laws regulating marriages and wills and prohibiting the abuse of the dead or the living. There were also sumptuary laws ("laws forbidding excessive public display of wealth"); these applied especially to women, limiting their adornments, what they could carry, and where they could go.

All of Solon's laws were set up in the Agora ("marketplace") of Athens, inscribed on axones, or kurbeis, boards that could be revolved for the reading of both sides. Every year, according to Aristotle, "the nine Archons . . . regularly affirmed by an oath . . . that they would dedicate a golden statue if they ever should be found to have transgressed one of the laws."

Moves Athens Toward Democracy

Aristotle also emphasized the most democratic of Solon's reforms: (1) the abolishment of debt slavery; (2) a provision enabling any citizen to undertake action in court for someone who has been wronged; and (3) the right of appeal to a jury court. Solon certainly moved the constitution of Athens in a democratic direction. He did not, however, create a full democracy. Rather, as his writings attest, he achieved a mixed government that balanced the interests of rich and poor:

I gave the people as much privilege as they have a right to: I neither degraded them from rank nor gave them a free hand; and for those who already held the power and were envied for money, I worked it out that they also should have no cause for complaint. I stood there holding my sturdy shield over both the parties; I would not let either side win a victory that was wrong. Thus would the people be best off, with the leaders they follow: neither given excessive freedom nor put to restraint. . . . Acting where issues are great, it is hard to please all.

After receiving a promise from the people of Athens that they would obey his laws for at least ten years, Solon left the city to travel abroad, perhaps wishing to avoid constant requests to amend his decrees. He went to Egypt, where, according to Plato, he heard the tale of the lost continent of Atlantis. On Cyprus, he is said to have been honored by having a city (Soli) named after him. Herodotus credited him with a visit to Lydia and a conversation with King Croesus that appears impossible on chronological grounds, as Croesus's reign began in 560 b.c. According to Herodotus, Croesus--the richest man in the world--asked Solon to name the happiest man be had ever met or heard of, expecting Solon to choose Croesus himself. Instead, Solon recalled an Athenian citizen who had died in battle, and two Argives who received death as a gift after pulling the chariot of their mother, a priestess of Hera, to a festival. Solon's point--that the happiness of a human life may not be judged until it is over--did not escape Croesus's anger.

Returning to Athens, Solon discovered that while his reforms had satisfied some citizens, there were many yet unsatisfied. The citizens had splintered into three parties based on economic interests and family loyalty. The first group of moderates was called the Party of the Shore; the second group of reactionaries, including most of the Eupatrids, was the Party of the Plain; and the third group of radicals was the Party of the Hill. Pisistratus, as champion of the common people, became the head of the Party of the Hill, and in 561 b.c., he seized power. Solon, seeing his life's work apparently being swept away, broke with his kinsman and former good friend, whose tyranny he then opposed. Some authors record that Solon left Athens to live in Cyprus for the last months or years of his life. After his death in approximately 558 b.c., his bones were returned to Salamis, the island he had recovered for Athens and which may have been his native land.

Pisistratus kept Solon's laws nominally in effect through much of the sixth century, although he ran the state as a benevolent despot. From 508 to 507 b.c., Cleisthenes modified the constitution so as to make Athens a true democracy, at least insofar as the citizens were concerned. Solon was remembered in Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries b.c. as having been the greatest of lawgivers. Both liberals and conservatives appealed to his authority for their own programs. With so great a reputation, the story of his life rapidly took on the quality of political myth, so that accounts written of him in ancient times offer an indistinguishable line between history and legend.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Name variations: Solon, son of Execestides (sometimes incorrectly called son of Euphorion). Born about 638 b.c., perhaps on the island of Salamis; died about 558 b.c., possibly on the island of Cyprus; son of the Athenian noble Execestides (a descendant of Codrus, last king of Athens); his mother's name is unknown; married: unknown; children: unknown. Predecessor: The position of archon was filled annually by election, and his immediate predecessor is unknown. Successor: After Solon, there was a chaotic period; within the next nine years, the archonship was twice left vacant, and one archon, Damasias, held onto the office illegally for two years and two months.

CHRONOLOGY

* 638 b.c. Born, possibly on the island of Salamis

* 632 b.c. Cylon attempted to establish a tyranny in Athens

* 621 b.c. Laws of Athens codified by Dracon

* 596? b.c. Solon led the recapture of Salamis from the Megarians

* 594 b.c. Elected chief archon ("leader") of Athens for one year; start of his reforms

* 593 b.c. Left Athens for ten years to travel abroad

* 583 b.c. Returned to Athens

* 561 b.c. Pisistratus seized power; Solon left Athens

* 558 b.c. Death of Solon on Cyprus; his bones taken to Salamis

* 508 b.c. Reforms of Cleisthenes; Athens became fully democratic, at least as far as citizens were concerned