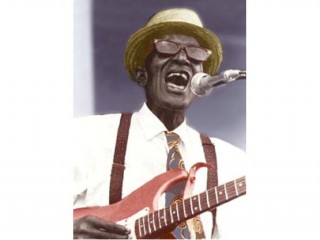

Sleepy John Estes biography

Date of birth : 1899-01-25

Date of death : 1977-06-05

Birthplace : Ripley, Lauderdale County, Tennessee

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-11-12

Credited as : blues guitarist, songwriter, Big Bill Blues, Big Bill Broonzy

1 votes so far

His parents were sharecroppers who had sixteen children. Like his brothers and sisters, Estes grew up working his parents' fields. There was little time for school. The most traumatic event of his childhood occurred during a baseball game when a stone struck him in the eye. He lost his vision completely in one eye and his other grew worse and worse until, by his fifties, he was left completely blind. Some say his poor eyesight gave him the appearance that led his friends to nickname him "Sleepy;" others say it was just his penchant for falling asleep on the bandstand during his gigs.

Estes' father, who played guitar, was probably the first musician he ever heard. His father showed Estes a few chords, let him play his guitar occasionally, and taught him his first song, a ditty called "Chocolate Drop." Before long Estes had built his own cigar-box instruments on which he practiced. In 1915 the Estes family moved to Brownsville where John hooked up with David Campbell, a local musician who showed him a little more about playing the guitar. Before long Estes was playing local fish fries, frolics, and house parties in the area. A decisive influence was another local musician, Hambone Willie Newbern. Newbern has won a minor place in blues history as the composer of "Roll and Tumble," which became a blues standard eventually recorded by postwar Chicago artists such as Baby Face Leroy and Muddy Waters, and even the British rock group Cream. Newbern took Estes under his wing and before long they were performing together up and down the Mississippi, hitting points as far-flung as Como, Mississippi, down in the Delta.

Despite all his blues schooling, Estes' guitar playing remained rudimentary at best. It never reached the expressiveness, invention, or power of Charlie Patton, Robert Johnson, or Bukka White. It was merely a convenient vehicle to accompany his singing. But it was his singing that propelled his career. Estes' voice produced a high, plaintive cry that was ageless-it could have been a decrepit old man singing or a teen whose voice had not yet broken. It was a wail, full of pain and pathos. Its sound alone articulated everything the blues represented: loss, despair, loneliness, hurt.

By 1919 he was a popular performer around Brownsville. Reason enough, when his father passed away, for Estes to walk away from the farming he despised. Though Estes wasn't a particularly strong instrumentalist, he managed to surround himself with others who were. He met James "Yank" Rachell around 1920 when he heard another musician was playing a frolic he had expected to be his. His intention was to run off the newcomer. Instead he liked what he heard, and he and Rachell teamed up and started playing square dances and house parties around town, for whites and blacks alike. Rachell had been playing guitar when Estes first heard him, but he soon switched to his second instrument, mandolin.

Later in the 1920s Estes met harmonica player Hammie Nixon, an important figure in the development of blues harmonica. Nixon learned to play from Noah Lewis, the first great modern harp player, and went on to teach James "Sonny Boy" Williamson, one of the first to adapt the harp to urban blues. Estes and Nixon traveled and played together occasionally in the early and mid-1920s. Around the same time Estes met Son Bonds, a Brownsville guitarist. Estes would use these three men on virtually all of his records, up into the late 1960s in the case of Nixon and Rachell.

Every autumn Estes made it a point to play in Memphis, when the city was overflowing with money from the harvest. On one trip, he and Rachell teamed up with Jab Jones, an occasional member of the Memphis Jug Band, to cash themselves in on the jug band fad. They formed the Three J's Jug Band, with Estes singing and playing guitar, Rachell on mandolin, and Jones blowing jug. They were good enough to catch the attention of Jim Jackson, one of the most popular musicians in Memphis. Jackson offered to act as their agent around Memphis. For reasons known only to them-perhaps they were worried that Jackson would cheat them-they refused the offer, preferring to fend for themselves.

When the jug craze petered out toward the end of the 1920s, Jones switched back to his first instrument, piano. That was how they recorded at Estes' first session in 1929 with the Victor label. The music they made is some of the most unique and interesting in country blues. Jones' deft piano provided the foundation of the music. Rachell soared above on his mandolin, with Estes in between with his keening voice and solid double-time strumming on guitar. It was, in the words of Don Kent's liner notes to I Ain't Gonna Be Worried No More, "a session of masterpieces." It produced a cover of a blues chestnut, "Milk Cow Blues," but Estes version never got around to mentioning the cow! It produced an Estes original, "Street Car Blues," possibly the only blues ever written on the subject. Estes' version of Newbern's "Roll and Tumble," entitled "The Girl I Love She Got Long Curly Hair," was Estes' first single and turned out to be one of his most popular as well. The three musicians were reportedly paid $300 each for the session, a royal sum at the time for most any musician. They pocketed the cash and headed straight to the notorious river town, West Helena, Arkansas, where they quickly squandered all of it on drinking, gambling, and general carousing. Rachell had to pawn his watch to get back to Brownsville.

Estes' records were popular and their sales were good, at least until the Depression deepened and the poor could no longer afford luxuries like phonograph records. Estes made his base in Brownsville where he continued to live and perform, while making regular sorties into Arkansas and Missouri. He went up to Chicago occasionally as well and even claimed to have played for gangster Al Capone, who Estes said was crazy about blues. Despite the popularity of his 1929 records, Estes was not able to record again during the first three years of the 1930s. When he heard that Nixon and Son Bonds had just returned from recording in Chicago, he persuaded Nixon to return to the Windy City and set up a session for him. Finally, in 1934 Estes returned to the studio with Hammie Nixon to record for the Decca label. At the session Estes cut "Someday Baby" and "Drop Down Mama," songs that went on to become blues standards, recorded by the likes of Big Joe Williams, Big Maceo, Big Boy Crudup, and Muddy Waters.

After the 1934 session Estes moved to Chicago where he lived for most of the 1930s. His popularity grew. In 1937 his photo graced the cover of Decca's race record catalog. At his next sessions Estes' song-writing style, in which he would sing directly of his own life and that of his Brownsville friends and neighbors, began to take shape. In 1937 he recorded "Floating Bridge," about being swept off a bridge by a raging river and rescued at the last minute by Hammie Nixon. In 1938 he wrote "Fire Department Blues" about his neighbor Martha Hardin. "She's a hard-working woman, her salary is very small/Then when she pay up her house rent, that don't leave anything for insurance at all/Now I wrote Martha a letter, five days later it returned back to me/You know little Martha's house done burned down, she done moved over Bedford Street."

His last session in 1941 saw his musical chronicle of Brownsville in full flower. He sang about a local lawyer, Mr. Clark, who worked as hard for the poor who couldn't pay as much as for the rich who could. He sang about little Laura whose sexual fantasies had a way of all coming true. And he sang about how machines were pushing sharecroppers off the land around town.

That session was Estes' last for some 20 years. Times were changing, not only down on the farm, but in music too. By the 1940s Estes was a vestige of a music-the pure country blues-that had all but died out and been replaced by more sophisticated blues, the so-called "urban blues." Estes disappeared back down into Tennessee. He and Hammie Nixon reportedly made a trip to Memphis to record for Sam Phillips Sun label in 1948, but little came of it.

Sleepy John Estes was all but forgotten until the folk revivalists of the 1950s set out to track down as many of the old recording artists as they could find. Unfortunately, inaccurate rumors about Estes abounded. In his biography, Big Bill Blues, Big Bill Broonzy wrote that as a child he had seen Estes play at a railroad camp. Estes was 20 years older than he was, Broonzy wrote, and long dead. Imagine the surprise when filmmaker David Blumenthal finally found Estes, tracked down on a tip from Big Joe Williams via Memphis Slim. He looked like a man in his seventies, but he was only 58-eleven years younger than Broonzy! He was found in a ramshackle shack on an abandoned farm with his wife and five children, "living in harsh poverty that was deeply disturbing to see," wrote Samuel Charters in Sweeter Than The Showers Of Rain.

Estes' career somehow picked up where it had left off. Producer Bob Koester took over, setting up appearances at festivals. The most important was the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, when he was reintroduced to the world. He went on to tour Europe twice in 1964 and 1968 with the American Folk Blues Festival. He was a celebrated guest at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in 1969. And in November, 1974 he became the first country bluesman to perform in Japan. Estes made records regularly, up to his death practically, the best being three he did for the Delmark label in Chicago. He frequently worked with his old partners, Yank Rachell and Hammie Nixon, in the 1960s. Sleepy John Estes died on June 5, 1977.

Selected discography:

-I Ain't Gonna Be Worried No More , Yazoo.

-First Recordings , JSP.

-1935-1938 , Black & Blue.

-The Legend of Sleepy John Estes , Delmark.

-Broke & Hungry , Delmark.

-Brownsville Blues , Delmark.