Simon Rattle biography

Date of birth : 1955-01-19

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Liverpool, England

Nationality : English

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2012-01-11

Credited as : Conductor, conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, conductor of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

0 votes so far

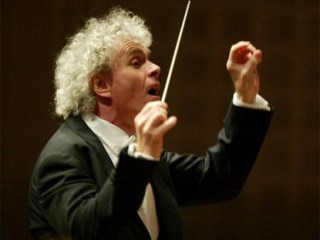

Simon Rattle has been hailed as one of the best in a new generation of baton wielders in the classical music world. Associated for nearly 20 years with Birmingham, England's, civic symphony, Rattle has also enjoyed a long and prolific career as a guest conductor with some of the most esteemed philharmonics and orchestras in Europe and North America, and has been honored with dozens of awards, including a Grammy Award in 2001. Time International writer Aisha Labi noted that Rattle "seems at first glance an unlikely icon. He sports impish good looks and a distinctive mane of tousled curls. But it is Rattle's vitality and catholic approach to the musical canon that have won him international acclaim."

Unlike many in his field, Rattle did not build his career and reputation working with the standards of classical music--the canon of Beethoven, Wagner, Mozart--but instead sought to introduce classical audiences to a more modern repertoire. In 2001 he even recorded new arrangements of jazz composer Duke Ellington's best-known songs for his longtime label, EMI. A veteran music writer the British Guardian newspaper, Nicholas Kenyon, termed Rattle "a musician for the twenty-first century, equally at ease with a large symphony orchestra or with an early music group, a contemporary music ensemble or jazz band."

Rattle was born in 1955 in Liverpool. His father Denis, an import-export company manager, took him to performances of the local youth ensemble, Merseyside Youth Orchestra. His interest in music was apparent early on, and Rattle began studying piano at the age of six. A sister, older by nine years, worked as librarian, and brought home classical records and later, musical scores, to feed his interest. As Rattle's ability progressed, he began to study with a well-known virtuoso, Douglas Miller, winning a place in a prestigious summer school program for budding musicians near Vienna. At the age of 15 he gathered an orchestra to stage a charity event at Liverpool's College Hall and conducted it himself; the evening was a rousing success. A year later, he was conducting the Merseyside Youth Orchestra and appearing as a percussionist with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

Rattle's formal university training consisted of three years at London's Royal Academy of Music in the early 1970s. Originally a piano and percussion student, he soon moved to conducting. A 1973 student performance of Mahler's Second Symphony earned rave reviews and advanced his reputation as an up-and-coming name in British classical music. The following year he took first prize in the John Player International Conductors' Competition, which brought a fair amount of press attention--and offers to conduct orchestras and philharmonics on both sides of the Atlantic. After one spot with Berlin's radio orchestra in 1976 that earned poor reviews, Rattle began to choose his engagements more carefully. "If I'd said yes to all those concerts I was offered, I'd now be a bitter percussionist somewhere, because I couldn't do it and the orchestras would have seen through me," he told Kenyon in the Guardian.

Instead Rattle worked steadily with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra as an assistant conductor and as associate conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. In 1980 he was offered the top job with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO). It was not considered a career-making post for a young conductor (he was just 25 years old), for at that time it was a lackluster orchestra. Within a few years, however, critics were hailing him as its savior. Rattle turned it into a first-class group that even earned a Grammy Award nomination. New York Times writer James B. Oestreich wrote that the conductor and musical director applied to the CBSO "a single-mindedness and dedication that went out of fashion decades ago, and he is widely credited with having transformed it from a provincial band into, on any given night, one of the finest and most adventurous ensembles in England."

As Rattle's renown grew, lucrative offers of permanent contracts came from other orchestras. He steadily declined them, but made guest-conductor appearances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; he also began working with the Rotterdam Orchestra and the famed Berlin Philharmonic, with which he made his conducting debut in 1987. Meanwhile, the CBSO's reputation strengthened. Its chief persuaded the city to fund a new home for it, Symphony Hall, and launched a composer-in-residence program--a relatively new concept in Britain--that brought Judith Weir, Oliver Knussen, and Thomas Adès to work with it. Rattle fostered the careers of other rising stars in the classical world in other ways: in 1989, he commissioned an opera from a young composer, Mark-Anthony Turnage, based on artist Francis Bacon's portraits of three popes. The result was Three Screaming Popes, which premiered in 1993.

Rattle also worked with avant-garde French composer Pierre Boulez, one of the greatest living serial musicians, for a series of modern-music concerts with the CBSO. His attempt to bring traditionalist and "new" music together was a renegade strategy when he began in late 1970s, as Guardian writer Fiona Maddocks explained. Back then, "contemporary music was a weird minority interest, remote from the mainstream of ordinary concert life. Rattle, by his youth and universal appeal, made it normal to sit through a tricky world premiere in a mainstream concert and find it exciting," Maddocks asserted.

Rattle's conducting style is an energetic one. Edward W. Said, music critic for the Nation, compared his podium manner to that of the other leading names of the era: Georg Solti, James Levine, and Claudio Abbado. Said had witnessed a 1993 Rattle performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the Tanglewood Festival, and found that he "supplied a remarkable confluence of physical gesture and supple sound that few conductors today can match." Reviewing a 1994 performance of Berlioz's La damnation de Faust with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, American Record Guide writer Richard S.

Ginell wrote, "[a]s with his own English orchestra in Birmingham, he is particularly good at getting people to play very softly, and he summoned melting sounds out of the strings at the outset and in the wonderfully delicate 'Dance of the Sylphs.'" New Statesman's Dermot Clinch described one of Rattle's displays at the podium, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in 1999. "Sometimes he bent his knees, puffed his cheeks and mimed a straw-chewing yokel, to encourage a proportionate rustic attitude in his players. That was especially during Beethoven's 'Pastoral' Symphony," wrote Clinch. "During the pizzicato interlude in Mahler's Second Symphony, 'The Resurrection,' he dropped his hands to his sides and encouraged his band just to pluck 'n' swing."

Rattle has recorded several works each year since the early 1980s, producing a repertoire ranging from Mahler and Strauss to twentieth-century British composer Benjamin Britten. The Birmingham Symphony and pianist Lars Vogt recorded two Beethoven piano concertos in the mid-1990s under Rattle, and American Record Guide reviewer Allen Linkowski praised Rattle's achievement with both the CBSO and its soloist, terming the recordings "a real collaboration. He brings both scores to life, revealing details more often than not lost in other interpretations."

Rattle also possesses a keen interest in period instruments. Since 1992 he has conducted the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (OAE), which uses baroque instruments like the flügelhorn and harpsichord, at the annual Glyndebourne Festival and in London concerts. In 1999 he conducted the OAE and the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group in a program of Haydn, Beethoven, and a specially commissioned piece by Turnage for both ensembles for the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) Millennium Concert. A 2001 performance of three Mozart symphonies prompted Guardian writer Erica Jeal to commend both conductor and players. Jeal noted that though each of the three was "standard orchestral repertoire ... Rattle can be relied upon to make music of this period sound anything but basic.... As ever, Rattle cut a dynamic figure on the podium, and his attention to detail let nothing slip."

As Rattle's international performing and recording reputation grew, he was predicted to succeed Seiji Ozawa at the Boston Symphony Orchestra, should that job opening arise. It was also rumored that the Philadelphia Orchestra was eager to sign him. To the surprise of many, he was chosen to become the next musical director of the esteemed Berlin Philharmonic in 1999. His legendary predecessors were Wilhelm Fürtwängler, Herbert von Karajan and, of late, Claudio Abbado. Time International's Labi called the Berlin conducting job "one of the most coveted podiums in the world." Rattle's hire also spoke volumes about his reputation. For generations, there had been a deep bias in Europe--especially in Germany--against British music, and Rattle's hire was a surprise to many. Guardian writer Andrew Clements called it "the highest distinction that any British conductor has ever achieved."

Rattle was elected by the philharmonic body itself--yet another sign of its unique reputation--over Daniel Barenboim, music director of the Berlin Staatsoper and the Chicago Symphony. The Israeli-Argentine pianist and conductor was viewed as more of a traditionalist, with a repertoire squarely grounded in the canon of nineteenth-century Austro-German composers. Rattle, by contrast, had performed and recorded admirably in a range of styles, from baroque to new music. "Symphony orchestras are still essentially nineteenth-century institutions, playing a predominantly nineteenth-century repertory," explained Clements in the Guardian. "That the Berlin players finally opted for Rattle over Barenboim, indicates that at least a majority of them realise the need for the Philharmonic to change, to look forward to the new century...." Clements hailed the choice as the marker of a new era for the venerated Berlin Philharmonic, predicting that Rattle would help it lure "a new, younger audience in a city that is consciously and literally rebuilding itself at the centre of Europe."

Rattle concurred with the idea that Berlin desired a new change in the interview with Oestreich for the New York Times. "It's been made abundantly clear that they feel they cannot simply dig the same old gold mine, however wonderful," Rattle stated. As a harbinger of an impressive future collaboration, Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic won a Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance in 2001 for Mahler's Symphony No. 10. Sensible Sound reviewer Karl W. Nehring commended the recording, stating that Rattle "loves this music, the orchestra plays with precision, and this really is a disc that Mahler lovers ought to hear."

Rattle was slated to take the Berlin job permanently with its 2002 season, although in 2001 rumors surfaced that disagreements had stalled the contract. At the same time some in Britain wondered why its own cultural institutions had been unable to keep him at home. Kenyon, the Guardian music writer who has authored two biographies of Rattle, speculated that he was somewhat underappreciated in London. One conductor, John Carewe, concurred, and asserted that the Rattle's departure for Berlin should instead inspire a renewal of the London musical scene, and someday Rattle would return to it to lead. If not, Carewe told the Guardian, "Ten years after he dies, there will be a concert hall built here in memory of Simon Rattle. And a fat lot of use that will be."

Rattle's Berlin post would take five months of each year, and he planned to maintain his London residence, which he shares with his American-born wife. He has two sons from his previous marriage who live with their mother, soprano Elise Ross, in San Francisco. He pledged to begin studying the German language in earnest, but would only commit to working with the Vienna Philharmonic as a guest conductor for performances and recording. He admitted to working much less than he did in his thirties in the New York Times interview. "I don't want to work much more than seven months of the year, just because I don't think you can stay creative," he explained to Oestreich just after his forty-fifth birthday. "I need more and more time ... to do things that aren't music, to read and to discover."