Simeon Rice biography

Date of birth : 1974-02-24

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Chicago, Illinois, USA

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-23

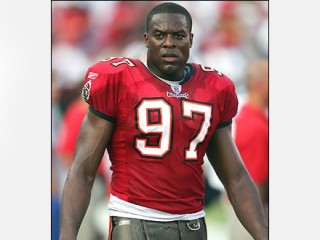

Credited as : Football player NFL, currently plays for the the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, plays in Super Bowl

0 votes so far

Simeon Rice entered the world on February 24, 1974, in Chicago, Illinois. He was the second boy born to Henry and Evelyn Rice. Older brother Diallo came first and four sisters would follow. The Rices lived in a five-bedroom house on Chicago's South Side. Henry worked on the assembly line at Ford and Evelyn was a schoolteacher who worked with troubled kids. Over the years, the couple saw their Rosedale neighborhood change in distressing ways, as gangs like the Gangster Disciples and Vicelords fought for control of the streets.

Though he heeded his parents' warnings to steer clear of these violent groups, Simeon was no angel. The youngster was the wildest of Henry and Evelyn's six children. In the belief that a nurturing academic experience might focus their son, they arranged for him to attend crosstown George Washington Elementary. Simeon rebelled, mouthing off to teachers and on occasion taking swings at them. Henry often received calls from school, summoning him to take Simeon home.

This didn't fly with Simeon's dad, an imposing physical presence and strict disciplinarian who preached the value of a good education—and could back up his words if need be. Henry once became so exasperated by his son that he threatened to hold his head underwater. Scared to death, Simeon straightened up. But as he got older, he still found plenty of trouble. Once he and a friend broke into what they thought was an abandoned house, only to run into a man brandishing a gun.

Though they didn't view professional sports as an ideal career path, Henry and Evelyn were grateful when Simeon became interested in football. He and Diallo spent hours playing pick-up games with their friends, and when everyone went home, Simeon would beg his father to play with him. He dreamed of being the next Walter Payton.

Henry could see that Simeon had the potential to be an extraordinary athlete. His son was tall, powerful and incredibly fast. Fearing he might become too reliant on his natural gifts, Henry harped on the need for hard work and commitment.

Henry and Evelyn, devoted members of the Adventist Church, also made sure their children shared their religious beliefs. To their delight, Simeon gravitated toward the Pathfinders, a youth group similar to the Boy Scouts.

When Simeon was ready for high school, Henry and Evelyn decided to send him to the highly structured Mt. Carmel, an all-boys Catholic school that Simeon found genuinely unappealing. He had to take the bus an hour or more each way, through some scary neighborhoods, to the Mt. Carmel campus, which was located near the University of Chicago.

The Caravan had a proud football tradition. In the 1940s, Notre Dame football coach Frank Leahy began recruiting the school's top players. Terry Brennan, Mt. Carmel class of 1945, replaced Leahy in 1953, further strengthening the pipeline to the Fighting Irish. Frank Lenti headed the football program when Simeon arrived in the fall of 1988. By then state championships were expected, so cracking the varsity starting lineup was extremely difficult. During his first two years at Mt. Carmel, Simeon did not see much game time. A running back, he stood more than six feet tall and could outrun just about everyone on the team. But the Caravan roster was deep, so he had to work his way up the ladder.

Prior to Simeon's junior season, coach Lenti decided to switch him to tight end and defensive end. The 16-year-old fought the move. In practice, he deliberately dropped passes and missed tackles. Mt. Carmel went on to win its third state title in a row, but once again Simeon hardly ever got into the huddle.

Coach Lenti had a frank discussion with Simeon as he prepared for his senior season. There was still time for him to realize his potential in football, he said, but Simeon would have to accept the fact that he was best suited for defense. The senior accepted his fate, realizing it was the only way to further his gridiron ambitions.

Simeon played his final year for Mt. carmel like a man making up for lost time. In a sense, he was. College recruiters had no idea who he was, so every game was critically important. Maximizing his raw athletic ability, Simeon dominated opponents with his speed and power. From the first contest of the campaign—against Joliet Catholic and its star fullback, Mike Alstott—through the 5-A championship game, he got better by the week. With the state title on the line and Mt. Carmel trailing 14-7, Simeon turned the tide with a fourth-quarter sack that caused a turnover. The Caravan used the play to fuel a dramatic comeback victory.

Throughout the season, Lenti implored college coaches to give Simeon a look. Few listened. Simeon went on recruiting trips to Boston College and Louisville, but neither school interested him. He wound up at the University of Illinois in Champaign, just a few hours from home.

ON THE RISE

It didn't take long for Illini head coach Lou Tepper and defensive coordinator Denny Marcin to realize that they had lucked into a special player. At 6-4 and close to 220 pounds, Simeon needed to bulk up, but his explosiveness and knack for making big plays made him a standout from his first scrimmage. After three days of practice, Marcin told Simeon's parents that their son was destined for greatness. The assistant coach knew a thing or two about kids with bright futures. He had coached Lawrence Taylor at North Carolina; in Simeon, he saw many of the same qualities.

Simeon was a perfect fit for the Illini's attacking 3-4 defense. Tepper and Marcin installed him at outside linebacker, and set him loose on opposing quarterbacks. He joined sophomores Dana Howard and John Holecek and fellow frosh Kevin Hardy to form one of the most impressive group of linebackers in the nation. In Illinois's third game, against Houston, Simeon buried Cougar quarterback Jimmy Klingler three times and was named ABC's Player of the Game. He ended the campaign with nine sacks, a school rookie record. Voted second-team All-Big Ten, he was honored as the conference's Freshman of the Year.

Illinois depended mightily on its defense in 1992, for its offense had trouble scoring points. The Blue and Orange finished in the middle of the Big Ten at 6-4-1, but still earned a berth in the Holiday Bowl. They lost to Hawaii 27-17.

Throughout the season, Simeon hit the books as hard as opposing quarterbacks. Unlike some teammates, he took his classes seriously. He'd known kids from the neighborhood who went off to college on an athletic scholarship and came back just as dumb as when they went in. He had no intention of disappointing his parents like that. A Speech Communications major, Simeon planned to load up on credits and graduate early if possible.

By contrast, the 1993 edition of the Fighting Illini shot blanks. Like the year before, they had trouble scoring points, despite the addition of former NFL QB Greg Landry to the coaching staff. And once again, the defense could only do so much, as the team finished 5-6. Simeon and his teammates were all guilty of trying to do too much, of trying to win games with big plays—a strategy that often backfired. The highlight of the year came against favored Michigan, when Simeon caused quarterback Todd Collins to fumble in the fourth quarter, then pounced on the loose ball. The play sparked Illinois to an upset victory.

Simeon's disappointing sophomore campaign motivated him to train harder than ever. When he wasn't in the classroom, he was in the weight room, adding muscle to his upper body and strengthening his legs. Howard, Holecek and Hardy joined him there. The foursome was recognized as the country's best linebacking crew as the 1994 season opened. Once again, however, the offense couldn't match their production, and the result was a 6-5 season. The campaign did end on a high note, with a 30-0 drubbing of East Carolina in the Liberty Bowl.

The shutout showcased the skills of Simeon and his linebacking mates, all of whom had superb seasons. Howard won the Butkus Award, Holecek solidified his standing in the NFL Draft, and Hardy, who registered 80 tackles and two interceptions, was voted the team's MVP. Simeon, meanwhile, set a school record with 16 sacks and was named by AP as a Second-Team All-American. Five of his sacks came in the season opener against Washington State. He also blocked a field goal and recovered a fumble in that game. By November, opponents were having to devise special blocking schemes to keep Simeon out of the backfield.

After the season, Simeon and his parents were shocked to hear analyst Mel Kiper say that he might be the top pick in the NFL draft. Simeon definitely wanted to play in the pros, but had assumed he would need four college seasons to build his draft-day resume. The Rices were afraid that their son would be lured out of school before he graduated. Coach Tepper, enraged by Kiper's comment, got on the phone with some NFL scouts and coaches, all of whom said that if Simeon were to go in the first round, it would be in the bottom half. This made the decision to stay at Illinois an easy one for Simeon.

With their best player committed to a fourth and final season, the sports information folks at Illinois cranked up their campaign to get Simeon some Heisman Trophy attention. Others in the running were Leeland McElroy of Texas A&M, Tommie Frazier and Lawrence Phillips of Nebraska, Stephen Davis of Auburn and Ron Powlus of Notre Dame. The odds were stacked against Simeon. In the previous 30 years, only nine defensive players had finished in the top five in the voting for the Heisman. Washington's Steve Emtman in 1991 and Florida State's Marvin Jones in 1992 were the most recent defenders to even get a sniff of the award. Hugh Green, Pittsburgh's outstanding outside linebacker, got closer to the prize than anyone, finishing second in the balloting to George Rogers in 1980.

As it turned out, Simeon never really had a chance. Illinois's offense, now under the command of Paul Schudel, was lousy again—and Heisman voters don't pay much attention to guys on 5-5-1 teams. Simeon's season was not devoid of Heisman-quality highlights, however. He was a force on defense, recording 12.5 sacks and making a bunch of All-America teams. In a 9-7 win over Arizona, he passed Michigan's Mark Messner as the Big Ten's all-time sack leader. Simeon also lived up to his promise of graduating on time, earning his degree by the end of the first semester.

That was one of the things NFL scouts liked most about Simeon. He was obviously intelligent and mature, qualities necessary for a surefire first-round draft choice. His physical skills were unquestioned, too, particularly his ability to rush the quarterback. Simeon clocked times between 4.5 and 4.6 in the 40-yard dash, and his quickness off the ball was outstanding. He was still drawing comparisons to Lawrence Taylor, while Tepper likened him to a player he had coached at Virginia Tech, Bruce Smith.

The only knock against Simeon was his size. He was projected as a defensive end, but at barely 250 pounds, he would need every bit of his intelligence and speed to outmaneuver the 300-pounders standing between him and NFL quarterbacks. For this reason, many teams debated the wisdom of gambling a pick on him.

Vince Tobin, the new head coach of the Cardinals, liked what he saw of Simeon. The team owned the third pick overall, and though there were holes to plug on his offensive line, Tobin couldn't resist. After Keyshawn Johnson and Kevin Hardy were selected, the Cardinals took Simeon over UCLA's mammoth tackle, Jonathan Ogden.

Simeon was not exactly overjoyed to be a Cardinal. The team was notoriously cheap, and he soon became embroiled in a contract squabble that lasted right through training camp. He finally signed a four-year, $9.5 million deal.

With the entire organization wondering how long it would take Simeon to get into playing shape, he suited up for the opener at defensive end and, on his first NFL down, exploded into the Indianapolis backfield and buried Marshall Faulk for a two-yard loss. A week later, Simeon dropped Dan Marino of the Dolphins for his first pro sack. At the end of September, with five sacks and a fumble recovery, he was named NFL Defensive Rookie of the Month.

Simeon continued to make the kind of plays that win close games—something the Cardinals desperately needed. In a 31-23 win over the New York Giants in November, he sacked Dave Brown twice. He also recorded two sacks a month later in a 27-26 victory over the Washington Redskins. That raised his season total to 12.5, which tied the rookie mark set by Leslie O'Neal of the San Diego Chargers in 1986.

A lot of credit for Simeon's success went to Joe Greene, Arizona's defensive line coach. The leader of Pittsburgh's Steel Curtain in the 1970s, “Mean Joe” worked with the rookie on and off the field. He offered crucial insight into the tricks of the trade for undersized defensive linemen, and twisted the rookie's arm to put in extra time in the film room. Greene also laid a little Henry Rice on Simeon from time to time, just to keep his ego in check.

The Cardinals improved from 4-12 to 7-9. At times, Tobin seemed to do his job with mirrors. He used Kent Graham at quarterback, flip-flopped between LeShon Johnson and rookie Leeland McElroy at running back, and had to patch together an offensive line because of injuries. The team's best player was fullback Larry Centers, who enjoyed an excellent season with 99 receptions. On defense, Aeneas Williams intercepted six passes and earned a trip to the Pro Bowl along with linebacker Eric Hill. Eric Swann also had a good year at defensive tackle. But Arizona's D had a long way to go, surrendering the most points in the NFC East.

The 1997 season started on a down note for Simeon, as he struggled through training camp with a viral infection that cost him 20 pounds and sapped him of his stamina. He still managed to record three sacks in the first two games, but never fully regained his strength. Making matters worse was the fact that opponents had learned the best way to attack him was to run right at him. Simeon fought gallantly enough to be named an alternate to the Pro Bowl, but was disappointed with his performance. In the final three games, his name barely showed up on the stat sheet.

The Cardinals lost seven of their first eight and finished 4-12. The defense was bad again, but at least the front four was improving. Eric Swann earned All-Pro honors, and newcomer Mark Smith enjoyed an outstanding year. The Cardinal offense showed signs of life, meanwhile, with young Jake Plummer seeing plenty of snaps and receiver Rob Moore catching 97 passes.

Still, the fans were growing tired of the hapless Cards. Their ire was directed at Simeon during the off-season, when they learned he was trying to hook on with a team in the Continental Basketball Association. Cut by the CBA's Ft. Wayne Fury, he ended up playing in the USBL with the Philadelphia Power. Simeon saw 11 minutes of action a night off the bench, averaged 2.5 points, and collected the princely sum of $400 a game.

The Arizona front office was none too pleased with Simeon's hoop dreams, and began to wonder about his attitude. When the team took Florida State defensive end Andre Wadsworth in the first round of the draft, the idea was to bookend he and Simeon. What the Cardinal brass did not say was that Wadsworth was also insurance in case Simeon wore out his welcome.

The addition of Wadsworth transformed the line, which averaged more than a sack a game despite losing Swann to a knee injury. The defense was also aided by draftee Corey Chavous, who proved a pretty fair corner opposite Aeneas Williams. The Cardinal offense was much improved, with Plummer pulling out several comeback wins on the way to a 9-7 record. In the diluted NFC East, that was good enough for a playoff berth. Arizona corralled the Dallas Cowboys, 20-7, to record the franchise's first post-season victory since 1947, when the Cardinals played in Chicago. A loss to the Viking the following week was disappointing, but did little to dim the luster of a very successful season.

For his part, Simeon led the team in sacks (10), quarterback pressures (23) and fumble recoveries (4). His performance against the Cowboys in the post-season underscored his value to the Cardinals. His speed rushes from the outside keyed Arizona's win, totally disrupting the timing of Troy Aikman and the Dallas passing attack.

Despite much promise, the next year was a bad one for the Cardinals. A strong draft and the players' newfound confidence could not offset several key injuries, and Arizona limped to a 6-10 record. Among Simeon's linemates, Smith sat out the entire year, and Wadsworth and Swann were in and out of the lineup all season long.

Simeon was Arizona's only real standout. He set a franchise mark with 16.5 sacks, placing him second in the NFL behind Kevin Carter of the St. Louis Rams. He opened the season with a monster effort against Philadelphia, making nine tackles and forcing three fumbles, and ended the year by sacking Brett Favre twice in Green Bay. Simeon's efforts were rewarded with his first appearance in the Pro Bowl.

With his original contract expired, Simeon was due for a big bump in pay in 2000. The subsequent negotiation dragged on through training camp, and he did not lay cleat on grass until the second game of the regular season. Missing training camp made it harder for Simeon to bounce back from injuries, and he went from being great (a career-high three sacks against the Eagles; eight tackles against the Redskins) to a non-factor. Not that anyone else was having a consistent year. The Cardinals stunk, turning over the ball again and again, and allowing 442 points on the way to a 3-13 record.

Simeon couldn't wait to escape Arizona. He set his sights on the Giants or Bears, but neither team showed the least bit of interest. In fact, no one was beating down his door. Simeon was viewed as a one-dimensional player who was great at rushing the passer but not exactly committed to stopping the run. When the Cardinals got into the habit of taking him out in goal line situations, this only strengthened the perception that he was unwilling to give up his body to stuff opposing ball carriers.

MAKING HIS MARK

Tony Dungy and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers were one of the few teams that saw Simeon as a worthwhile gamble. He signed a 5-year deal worth more than $30 million, but would make just $1 million for the 2001 campaign. Simeon and the Bucs seemed a perfect fit. Under Dungy, Tampa Bay had developed into a defensive powerhouse. Warren Sapp headlined a unit that dropped opposing quarterbacks 36 times, while Derrick Brooks anchored a superb linebacking corps and John Lynch led a hard-hitting secondary.

Tampa Bay regularly made the playoffs thanks to its defense, but in the previous four years had stumbled in the post-season because of a lackluster offense. Looking for more consistency, the team brought in Brad Johnson at quarterback. His primary weapons would be receiver Keyshawn Johnson and running backs Warrick Dunn and Mike Alstott, Simeon's old high-school rival. The offense also stood to benefit from the drafting of Kenyatta Walker, a huge tackle out of Florida.

The defense continued to shackle opponents in 2001—allowing less than 300 yards a game, intercepting 28 passes, and registering 42 sacks—but once again the offense couldn't produce when it counted. Johnson threw only 13 touchdowns, Alstott topped the team in rushing with just 680 yards, and Johnson hit paydirt only once despite 106 receptions. The Bucs made the playoffs again and drew a familiar foe, the Eagles. Veterans Stadium continued to be a house of horrors for Tampa Bay, as Donovan McNabb smoked them, 31-9.

Simeon had a great year. He recorded a team-high 11 sacks and led his fellow linemen with 64 tackles. His role in defensive coordinator Monte Kiffin's system was similar to the one he filled in college. Lined up on the far outside, Simeon was often let loose to rush the quarterback. He and Sapp were a dynamic duo. Whenever a team focused too much attention on one, the other exploited his one-on-one matchup.

Simeon was also putting up nice numbers against the run. Against the Vikings in September, he recorded six solo tackles. In a November game played in front of friends and family at Chicago's Soldier Field, he made five tackles, forced a fumble, sacked the quarterback, and batted down two passes. Simeon's best stretch came in December, when he was honored as the NFC Defensive Player of the Month. In five games, Simeon registered eight sacks and 21 tackles. He was also Tampa Bay's best performer in the Philadelphia playoff debacle.

The fallout from the Eagle loss led to the firing of Dungy. The Glazer family, who own the Bucs, had long wanted to replace him and now had the excuse they needed. When Al Davis made Jon Gruden available, Tampa Bay sent two No. 1 picks and two No. 2 picks to Oakland in return for the 38-year-old coach.

For the most part, Gruden liked the guys he already had, so he plugged in just a couple of role players, receiver Keenan McCardell and running back Michael Pittman—an old Arizona teammate of Simeon's. There was a quarterback battle in camp between Brad Johnson and Rob Johnson, with Brad keeping the starting job. The defense, meanwhile, required only a little fine-tuning. With the departure of linebacker Jamie Duncan, Sheldon Quarles moved from the outside to the middle.

Gruden's high-energy style was the most noticeable difference as the Buccaneers began their season. After a loss to the New Orleans Saints, the Bucs won nine of their next 10. Johnson flourished in the coach's controlled passing game, but even when he went down with an injury the Bucs rolled. Tampa Bay finished at 12-4, good for first place in the NFC North and a bye in the opening round of the playoffs.

Again, the defense was awesome, particularly Simeon. He started the year slowly, but was in full form by the end of October. Over one five-game stretch, he registered 11 sacks and forced four fumbles. For the year, his 15.5 sacks were tops in the NFC and second in the league.

The Buccaneers began the post-season by hosting the San Francisco 49ers, who were riding high after a rousing comeback victory over the Giants. The Tampa Bay D gutted the 49er attack, while Johnson returned to the starting lineup and played smartly. The contest was over by halftime, as the Bucs cruised 31-6.

Next up were the Eagles in the NFC Championship Game. Outside of a few bold prognosticators, no one thought Tampa Bay could win in Philadelphia. But the Bucs remained confident, even after the Eagles took a quick 7-0 lead. They battled back and went into intermission up by a touchdown. From there the defense seized control. Simeon, who spent most of the second half in the Philly backfield, was a major factor. When Ronde Barber returned an interception 92 yards for a touchdown, Tampa Bay sealed its 27-10 victory.

Leading up to Super Bowl XXXVII, most analysts thought the Raiders were too talented to be contained on offense. Oakland guard Frank Middleton fanned the fires with a verbal assault directed at Simeon, claiming he was no match for the Silver & Black's mammoth front line. Simeon could talk a good game, too—he once said he thought he would be the Michael Jordan of football defense—but he was unusually quiet as he prepared for his matchup against left tackle Barry Sims in the big game. He knew that his great year would do little to silence his critics if he disappeared in the Super Bowl.

Simeon made the first big play of the game for Tampa Bay, after an interception of a Johnson pass gave the Raiders terrific field position in the first quarter. With Oakland driving, he darted past Sims and buried Gannon on a third-down snap, forcing the Raiders to settle for a field goal. The sack changed the flow of the offense for the Raiders, as Gannon—who had put up MVP numbers in 2002 on quick drops—now heard Simeon's footsteps on every pass play. Minutes later Simeon was in Gannon's face again, this time causing a weak pass that safety Terry Jackson intercepted.

Simeon would continue to humiliate Sims in front of millions. He beat him inside, he beat him outside, and he beat him with power. (In general, he beat him like a drum.) When the Raiders were forced to help Sims, it opened the floodgates for Sapp and the rest of the line. Soon the rout was on. Simeon finished the contest with two sacks, five solo tackles and a take-down of Gannon on a 2-point conversion attempt. Tampa Bay blew out Oakland, 48-21, and anyone who knows anything about football knows that Simeon should have been named MVP of the game.

The Bucs entered the 2003 campaign with visions of a Super Bowl repeat dancing in their heads. Many of the experts agreed that they were primed to defend their title. Tampa Bay bolstered its offensive line with the addition of center John Wade and guard Jason Whittle. Also picked up in the off-season was running back Thomas Jones, a former first-round pick out of Virginia. The defense looked the same, except for Dwayne Rudd replacing Al Singleton at outside linebacker.

As it turned, however, nothing was the same in the '03 campaign. The theme of the year was off-the-field distractions. They started with Gruden writing his own book, and ended with the release of Keyshawn Johnson for disciplinary reasons. In between, the Bucs were decimated by injuries, including the loss of Mike Alstott, Brian Kelly and Kenyatta Walker. Despite some impressive individual performances—Johnson threw 26 TDs, and McCardell caught 84 passes—Tampa Bay limped home at 7-9 and out of the playoffs.

A major part of the problem was the defense. Simeon and his teammates never seemed able to stop opponents with the game on the line. Indeed, five of the team's defeats came with the Bucs tied or ahead in the fourth quarter.

For Simeon, 2003 was a success from a personal standpoint, on and off the gridiron. He began the season on an amazing roll, collecting eight sacks in his first five games. Of particular note was the way he dominated the Redskins in Week 6. On the day, Simeon notched six solo tackles, forced a fumble and buried the quarterback four times. He also enjoyed a big day against the Saints in December, dropping Aaron Brooks three times.

When it was all said and done, Simeon's 15 sacks were second in the NFL to New York's Michael Strahan. That helped earn him another trip to the Pro Bowl (though he was axed from the contest after the league claimed he was "almost late" for a workout).

The Bucs went into the off-season licking their wounds. The bleeding didn't stop. Jones, fresh off a promising season at halfback, bolted to the Bears only hours into the free-agency period. Meanwhile, McCardell was demanding either a raise or a trade, and threatened to sit out the 2004 campaign without one of the two.

Simeon experienced a scare during training camp when he was diagnosed with an irregular heartbeat. It was an ailment that he had dealt with since high school, so after a week on the sidelines, team doctors allowed him to return to the practice field. Though the condition never developed into a serious problem, it did affect Simeon’s preparation for the upcoming campaign.

On the other side of the ball, the Bucs made several moves to help their depleted offense. Gruden reunited with two of his old Raider buddies, running back Charlie Garner and receiver Tim Brown. The team also dealt Johnson to Dallas for fellow veteran receiver Joey Galloway. None of the three would live up to the expectations. Garner and Brown were hampered by injuries and played inconsistently. Galloway finished the campaign with 33 catches for 416 yards and five touchdowns.

Tampa Bay's most exciting acquisition was Michael Clayton of LSU, the 15th overall pick in the draft. The rookie emerged as a gamebreaker, amassing 1,193 yards receiving and seven touchdowns. But the Bucs needed more help than that. In the mediocre NFC, they hung around until December with a shot at the playoffs. But injuries at quarterback—Johnson, Chris Simms and Brian Griese all saw time—doomed Tampa, which limped home at 5-11.

Simeon entered the year hoping to challenge the franchise single-season sack record of 17. But he started slowly, posting just two sacks and 10 tackles through five games. Signs of the real Simeon appeared in October against the Bears. He spent the entire day in the Chicago backfield, embarrassing the banged-up Bear offensive line. Simeon ended the day with two sacks and two tackles, and his constant pressure keyed a 19-7 victory.

Simeon looked even more like himself in the next ten contests. During the stretch, he tallied eight sacks, and was a handful for just about everyone he faced. That included the Saints, who he terrorized with seven tackles and three sacks.

In the final analysis, Simeon turned in another solid campaign. In 16 starts (he has missed only one game in his career), he recorded 12 sacks and 40 tackles. He also received positive reviews for his first literary effort, Rush to Judgment, which was released in the fall of 2003. His line of performance apparel under the name T3K continued to sell well, too.

Tampa Bay's poor '03 and '04 seasons aside, Simeon has cemented his reputation as a true impact player. He has always wanted to be mentioned in the same breath as the NFL's all-time greats—if not before them. Thanks to his performance in Super Bowl XXXVII, he can claim the kind of memorable day Hall of Fame careers are built upon.

SIMEON THE PLAYER

Simeon's greatest asset is his speed. It takes most opponents by surprise—even those who are ready for it—and causes many offensive linemen to lose their concentration. Simeon knows this and uses his quickness to his advantage as an intimidation factor. It even allows him to take an inside route to the quarterback from time to time, which creates added havoc for slow-footed tackle and guards.

Simeon has extraordinarily long arms (his wing span measures 86 inches), which pose another threat when he's rushing the passer. There are times when a blocker believes he has forced Simeon out of the play by pushing him to the outside. But he's still able to reach the quarterback's throwing arm and knock the ball loose.

When Simeon broke into the NFL, he was too small to play defensive end every down. But he's now listed at nearly 270 pounds, enough bulk to take on bigger, more physical blockers. While strength will never be his prime weapon, he has developed a bull rush that is effective when employed at the right times.

Simeon has always walked to the beat of his own drummer. This was a problem early in his career, when some coaches, players and front office personnel interpreted his aloofness as being cocky, selfish or both. While some will always paint him with this brush, Simeon has demonstrated to teammates, executives and fans in Tampa that winning motivates him more than anything.

EXTRA

* Among Simeon’s classmates at Mt. Carmel were Donovan McNabb and Antoine Walker. He sponsors a scholarship tuition program at his high school alma mater.

* Simeon had an extensive collection of football cards as a kid. After his 15th birthday, he gave them all to a neighborhood friend who had just suffered a personal tragedy.

* Simeon ended his college career ninth on the Division 1-A list for sacks. The leaders at the time were Derrick Thomas (Alabama) and Tedy Bruschi (Arizona) with 52.

* Simeon says an alter ego overtakes him on game days. He calls the personality "Game," and swears he assumes complete control of his mind and body.

* Simeon was barely edged out by Dexter Jackson in the balloting for Super Bowl XXXVII MVP. He got six and a half votes to the safety’s eight.

* Simeon's father retired in 1997 after 30 years on the assembly line for Ford. The family received a scare four years later when Henry had to undergo triple bypass surgery. He came through the six-hour operation in good shape.