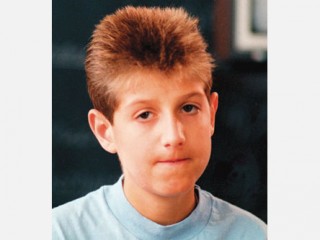

Ryan White biography

Date of birth : 1971-12-06

Date of death : 1990-04-08

Birthplace : Kokomo, Indiana, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-07-14

Credited as : Activist, ,

14 votes so far

Ryan White contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion when he was 13 and worked to educate people about the disease until his death at age 18. As a result of his efforts, and those of his mother Jeanne, Congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Care (CARE) Act, which provides health care resources to Americans with HIV/AIDS who have no insurance or not enough insurance to get proper care.

Ryan White was born on December 6, 1971 in Kokomo, Indiana. When he was three days old, doctors informed his parents that he had hemophilia, an inherited disease in which the blood does not clot. People who have this disease are vulnerable, since an injury as simple as a paper cut can lead to dangerous bleeding. Fortunately for White and his parents, a new treatment, called Factor VII, recently had been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This treatment is made from blood and contains the clotting agent that allows healthy people to heal quickly from wounds.

Even with the treatment, White had to be very careful. He bled easily and the most dangerous and painful bleeds occurred when a blood vessel bled in a joint. "A bleed occurs from a broken blood vessel or vein," White explained in his testimony before the President's Commission on AIDS. "The blood then had nowhere to go so it would swell up in a joint. You could compare it to trying to pour a quart of milk into a pint-sized container of milk." He was in and out of the hospital for the first six years of his life but despite this managed to live a fairly normal childhood.

In December 1984, when he was 13, White contracted pneumonia and had surgery to remove part of his left lung. After two hours of surgery, his doctors told his parents that he had contracted the incurable disease of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, or AIDS, through his Factor VII blood transfusions. Someone with the disease had donated blood, and the virus had been in the blood that White received. (Since that time, better screening procedures have been put in place to make blood transfusions safer). "I spent Christmas and the next thirty days in the hospital," White told the President's Commission on AIDS. "A lot of my time was spent searching, thinking and planning my life. I came face to face with death at 13 years old."

White's doctors told him that he had six months to live, but White decided that he would continue to live a normal life, attend school, and spend time with his friends. "I hate the idea of anything that makes me seem sick forever. Maybe I have an incurable disease, but I don't have to be a permanent invalid," he said in his book Ryan White: My Own Story.

Struggles Against Ignorance and Hatred

White had not counted on the ignorance, fear, and hatred he would encounter in his small home town of Kokomo, Indiana. At first, people there claimed that there were no health guidelines for a person with AIDS to attend a normal school. Even after the Indiana State Board of Health set guidelines saying it would be safe for the other children if White attended school, the school board, his teachers, and the principal tried to keep him out of school. They feared he would spread the disease, even though it was known by that time that AIDS cannot be spread by casual contact. White and his mother took the case to court. Eventually they agreed to meet some of their neighbors' concerns by having White use a separate restroom, not take gym class, drink out of a separate water fountain, and use disposable eating utensils and trays at lunch. Even so, 20 students were pulled out of school by their parents, who started their own school to keep their children from having any contact with White.

Ryan later told the Commission that his townspeople's ignorance and fear regarding AIDS led him to become the target of jokes and some spread lies about him biting people, spitting on vegetables and cookies (and thus supposedly spreading the disease), restaurants throwing away dishes he had eaten from and students vandalizing his locker and writing obscenities and anti-gay slurs (because at that time, AIDS was believed to be a disease primarily of gay men) on his books and folders. An even more frightening incident occurred when someone fired a bullet into White's home.

White told the Commission, "I was labeled a troublemaker, my mom an unfit mother and I was not welcome anywhere. People would get up and leave so they would not have to sit anywhere near me. Even at church, people would not shake my hand." This lack of acceptance, even in church, was a blow to the Whites, who were committed Christians. As White's mother told Phil Geoffrey Bond in Poz, a magazine for people with HIV and AIDS, "I worked with a Pentecostal [person] who told me, 'You know, Ryan wouldn't have AIDS if he went to my church.'"

Ryan wrote in his book, "I had plenty of time back then to think about why people were being mean. Of course it was because they were scared. Maybe it was because I wasn't that different from everybody else. I wasn't gay; I wasn't into drugs; I was just another kid from Kokomo....I didn't even look sick. Maybe that made me more of a goblin to some people."

White's Story is Publicized

White's ordeal was soon publicized and he began receiving enormous amounts of media attention. He received thousands of letters supporting his right to go to school, and met politicians, movie stars, and top athletes, all of whom supported him. He appeared on numerous television programs, including CBS Morning News, the Today Show, Sally Jessy Raphael, Phil Donohue, Hour Magazine, the Home Show, Peter Jennings' "Person of the Week," Nightline, West 57th Street, P.M. Magazine, Entertainment Tonight, and Prime Time Live. White was also featured on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, Picture Week, and People magazines.

Meanwhile, White's family was struggling with his medical expenses. As White became more ill, his mother had to miss more days from her work at General Motors and the family couldn't pay their bills. His sister Andrea, a championship roller skater, dropped her lessons and travel to competitions because the family simply did not have the money for them, or for anything else. White's health was steadily declining and he was being tutored at home. He dreamed of his family moving into a larger house and being accepted in a community. This dream became a reality when an ABC movie, The Ryan White Story, was made about his life. Ryan acted in the movie, playing his best friend, Chad. "I wanted to make that movie because I was hoping that what we went through will never happen to anyone else," White wrote in his book.

In 1987, using the money from the movie, White's family moved to Cicero, Indiana, where they found acceptance. "For the first time in three years," Ryan told the Commission, "we feel we have a home, a supportive school, and lots of friends....I am a normal, happy teenager again. I have a learner's permit. I attend sports functions and dances. My studies are important to me. I made the honor roll just recently, with two As and two Bs...I believe in myself as I look forward to graduating from Hamilton Heights High School in 1991."

AIDS Activism

Before White's experience was publicized, there had been no public reports of children who had AIDS. Following his diagnosis, White and his mother Jeanne became two of the world's best-known AIDS activists and educators. Jeanne founded the Ryan White Foundation, the only national organization in the United States devoted to HIV (human immunodeficiency virus, the virus that causes AIDS) and AIDS education for young people. They realized that much of the hatred aimed at White was the result of ignorance. "It was difficult, at times, to handle, but I tried to ignore the injustice," White wrote in his book, "because I knew the people were wrong. My family and I held no hatred for those people because we realized they were victims of their own ignorance. We had great faith that, with patience, understanding, and education, my family and I could be helpful in changing their minds and attitudes around."

When White was 16, he testified before the President's Commission on AIDS, describing his experience with bigotry as well as the financial difficulties his family had experienced as a result of his illness. White was a compelling spokesman but he was not alone. By 1991, local health departments, hospital emergency rooms and other health care providers experienced a surge in the number of patients who desperately needed care but could not pay for it. As the number of cases increased, many areas in the United States reported becoming overburdened with the cost of caring for people with AIDS who had little or no health insurance.

White died on April 8, 1990 in Cicero, Indiana. During his short 18-year life he accomplished more than many people who live long, healthy lives. His activism and legacy of concern for others with AIDS remains. "I've seen how people with HIV/AIDS are treated and I don't want others to be treated like I was," he said. Shortly after his death, White's mother went to Congress to speak to politicians on behalf of people with AIDS. She spoke to 23 representatives, although Jesse Helms of North Carolina refused to speak to her even when she was alone with him in an elevator. Most representatives, however, were sympathetic to her story.

White's activism, and that of his mother Jeanne, helped AIDS patients all over the United States receive care that they otherwise could not have afforded. The public was also educated about the nature of the disease. In 1990, just a few months after White's death, Congress passed P.L. 101-381, the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Care (CARE) Act. The Act is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration and aims to improve the quality of care for low-income or uninsured individuals and families with HIV and AIDS who do not have access to care. The Act supports locally developed care systems and is founded on partnership between the U.S. federal government, states, and local communities. It emphasizes outpatient, primary, and preventive care in order to prevent overuse of expensive emergency room and inpatient facilities.

Between the Act's authorization in 1991, and May of 1996, nearly $2.8 billion in federal funds were appropriated to provide care to more than 500,000 low-income Americans living with HIV or AIDS. From 1993 to 1996, funding for the program increased from $348 million to $738.5 million. The Act was reauthorized in May 1996 and continues to provide care to Americans living with HIV and AIDS.

White's mother, Jeanne, has collaborated with writer Susan Dworkin to write a book about her experiences with White, Weeding Out the Tears: Mother's Story of Love, Loss and Renewal, published in 1997. White wrote in his book, "...I drifted back to a question some kid asked me once. 'Would you give up all your fame to get rid of AIDS?' he wanted to know. How dumb can you get! I snapped my fingers at him. "Like that, I'd give it up like that.'"

AWARDS

Hemophilia Poster Child of Indiana; The Young Hero award; Indiana Civil Liberties award; Norman Vincent Peale award; Bob Hope "Spirit of America" award.