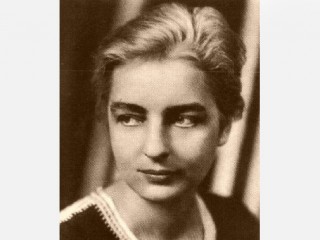

Ruth Benedict biography

Date of birth : 1887-06-05

Date of death : 1948-09-17

Birthplace : New York City, New York, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-08-19

Credited as : Writer, married to biochemist Stanley Benedict, won American Design Award for war service

2 votes so far

"Sidelights"

Ruth Benedict is a key figure in the development of anthropology in the twentieth century. Rejecting the restrictive Victorian cultural milieu into which she was born, she broke through many personal and professional boundaries, forging a place for herself as one of the leading anthropologists of her generation. Benedict did more than apply herself to anthropology; she used her findings to address contemporary social problems, seeking to transform the values and beliefs of American society. She was particularly influential in regard to race, deviancy, and the importance of culture in shaping personality. Her classic work Patterns of Culture established that individuals could indeed change their lives if they so desired.

Benedict was born in 1887 in New York City, where her father worked in medicine. After his untimely death at the age of thirty-one, Benedict's behavior showed indications of emotional instability, including violent rages. Later she regained a measure of self-control, but became withdrawn from her family members. Benedict also suffered a degree of deafness, a consequence of a bout with measles.

In spite of her shyness and hearing impairment, Benedict proved an excellent student. She eventually received a scholarship to Vassar College, from which she graduated in 1909. After completing her studies, Benedict returned to Buffalo, New York, where her mother had settled the family after years of travel, and found a position in social work. When the family moved to California in 1912, Benedict moved with them, and she obtained a teaching position at a girls' school.

In 1914 she married Stanley Benedict, a biochemist, with whom she moved to New York City. Benedict placed great importance on having children, but she herself was unable to do so. Her childlessness was devastating to her, and proved disastrous to her marriage, which eventually ended in divorce. In 1919, seeking to overcome bouts of depression, she abruptly enrolled at the New School for Social Research, where she befriended several prominent anthropologists, including Elsie Clews Parsons. Benedict also met Franz Boas, who taught anthropology at nearby Columbia University. Benedict eventually left the New School for Columbia University, where she studied under Boas. There she demonstrated keen prowess as a library researcher and data interpreter. Such skills are evident in The Conception of the Guardian Spirit in North America, her doctoral dissertation and first publication. It was derived largely from material research.

While teaching at Columbia University, Benedict met Margaret Mead, then a student. The two became friends and even had a romantic relationship. Mead eventually married, but the two women continued their professional collaborations. Their journals and letters record countless hours of discussion as they hammered out their theories. One common concern they shared was the concept of deviancy within a culture. Their discussions resulted in several, now classic, essays and books, including Mead's Coming of Age in Samoa and Benedict's highly influential Patterns of Culture. Patterns of Culture was the result of approximately ten years of work Benedict conducted among Native North Americans.

In Patterns of Culture, Benedict borrowed an idea from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, whose The Birth of Tragedy considered Greek culture in its Appollonian and Dionysian aspects. Benedict characterized the orderly, reserved Zunis of New Mexico as consistent with Nietzche's notion of Appollonian behavior, and she perceived the Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island as Dionysian in their apparent excesses. She also explored notions of normalcy, and argued that ethic and moral superiority is utterly subjective. Deviancy, Benedict charged, is specific to a culture's definitions of abnormalcy. That is, behavior that is objectionable in one culture may be quite acceptable in another culture. Everyone must therefore be regarded as equal without regard for cultural status.

Patterns of Culture appealed to both specialists and general readers. With it, Benedict helped establish anthropology as a provocative, radical field of study. Margaret M. Caffrey wrote in Ruth Benedict: Stranger in This Land: "Patterns of Culture did not initiate the trend but it confirmed anthropology as a source of moral authority in American life, superseding natural history." Likewise, Elgin Williams observed in the American Anthropologist that the "overriding contribution of Patterns of Culture is the liberalizing tradition of the science, the tradition which has shown itself already powerful in dealing with race prejudice and hatred."

Patterns of Culture has frequently been praised as an especially inspirational work. Judith Schachter Modell wrote in Ruth Benedict: Patterns of a Life: "Patterns of Culture established an intellectual attitude and conveyed an optimism about the ability of individuals to change their lives--a lesson from the author's own life and badly needed in the 1930s." And Caffrey declared in Ruth Benedict: Stranger In This Land, "For Ruth Benedict personally, Patterns of Culture represented a summation of the meaning of her life to that point. But it also marked a path into the future: for America, for anthropology, for herself." Patterns of Culture established Benedict as a leading figure in the field of anthropology. In ensuing publications, notably Race: Science and Politics and, with Gene Weltfish, The Races of Mankind, she continued to explicate the subjective nature of cultural superiority. In such works she espoused the notion, radical in some quarters, that all races are equal.

The Races of Mankind was an influential pamphlet that spoke out against prevailing, prejudiced attitudes in the mid-twentieth century. First published in 1943, it sold nearly one million copies over the next ten years. It was eventually transformed into a comic book, an educational cartoon, and the children's book In Henry's Backyard. Benedict also spoke out on racial equality through public lectures and articles, many collected in Mead's An Anthropologist at Work; she also often wrote letters to newspapers and magazines defending persecuted groups. Her efforts for peace continued the call for acknowledging and respecting differences.

In 1946, Benedict published The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture, a work that helped determine American attitudes toward Japan after World War II. In this book, Benedict examines Japanese culture's relatively rigid ethical code and its emphasis on loyalty and obligation. Gordon Bowles described The Chrysanthemum and the Sword in the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies as "an interpretation of Japanese personality and character primarily during periods of response to emotional stress." A. L. Kroeber wrote in the American Anthropologist that The Chrysanthemum and the Sword "is a book that makes one proud to be an anthropologist," and he added that the volume "shows what can be done with orientation and discipline even without speaking knowledge of the language and residence in the country."

Benedict always believed that lasting peace would come through cultural understanding, hence her enthusiasm for her final enormous undertaking. Margaret Mead and her husband, Gregory Bateson, had organized a Council on Intercultural Relations, for the purpose of studying human behavior. Reorganized in 1947 and funded by the Office of Naval Research, the Research in Contemporary Cultures department at Columbia University was headed up by Ruth Benedict. The organization enlisted the participation of most of the anthropologists committed to cultural relativity; its purpose was to study foreign origin groups in the United States. Its theories and techniques were unsupported by the scientific school of anthropology, so the institution had little impact at first, but its organization served as a model for future projects.

Benedict died in 1948, two years after completing The Chrysanthemum and the Sword. Though she came late to the field of anthropology, she nonetheless ranks among its key figures. Sidney W. Mintz, writing in Totems and Teachers: Perspectives on the History of Anthropology, deemed Benedict "one of [anthropology's] most distinguished and distinctive practitioners." He added, "That she wanted an anthropology of modern life made her a pioneer of [anthropology]. That she wanted social justice for all Americans, without regard to gender or race, makes her as modern as our times."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born June 5, 1887, in New York, NY; died of a heart attack, September 17, 1948, in New York, NY; daughter of Frederick (a surgeon) and Beatrice (a librarian; maiden name, Shattuck) Fulton; married Stanley Rossiter Benedict (a biochemist), June 16, 1914 (divorced). Education: Vassar College, A.B., 1909; graduate study of anthropology at New School for Social Research, 1918-19; Columbia University, Ph.D., 1923. Military/Wartime Service: Worked for Office of War Information during World War II. Memberships: American Anthropological Association (president, 1947), American Ethnological Society (president, 1927-29), American Folklore Society.

AWARDS

American Design Award for war service, 1946; Achievement Award, American Association of University Women, 1946.

CAREER

Anthropologist and writer. Worked as a social worker in Buffalo, NY, c. 1910-12; Orton School for Girls, Pasadena, CA, English teacher, 1912-13; Columbia University, New York, NY, lecturer, 1923-30, assistant professor, 1931-36, associate professor, 1936-48, director of Research in Contemporary Cultures Project (co-sponsored by Office of Naval Research), 1947-48, professor of anthropology, 1948.

WRITINGS

* The Conception of the Guardian Spirit in North America, American Anthropological Association, 1923.

* Tales of the Cochiti Indians, U.S. Government Printing Office (Washington, DC), 1931, reprinted, University of New Mexico Press (Albuquerque, NM), 1981.

* Patterns of Culture, Houghton Mifflin (Boston, MA), 1934, reissued with foreword by Mary Catherine Bateson and preface by Margaret Mead, Houghton Mifflin (Boston, MA), 1989.

* Zuni Mythology, two volumes, Columbia University Press (New York, NY), 1935.

* (With Gene Weltfish) Race: Science and Politics, Viking (New York, NY), 1940, revised edition published as Race: Science and Politics [and] The Races of Mankind, 1945, reprinted, Greenwood Press (Westport, CT), 1982.

* (With Gene Weltfish) The Races of Mankind, Public Affairs Committee (New York, NY), 1943, revised edition, 1961.

* Race and Cultural Relations: America's Answer to the Myth of a Master Race, National Education Association (Washington, DC), 1942.

* Race and Racism, Routledge (London, England), 1942.

* The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture, foreword by Ezra F. Vogel, Houghton Mifflin (Boston, MA), 1946.

* (With Gene Weltfish) In Henry's Backyard: The Races of Mankind, Schuman (New York, NY), 1948.

* An Anthropologist at Work: Writings of Ruth Benedict, edited by Margaret Mead, Houghton Mifflin (Boston, MA), 1959, reprinted, Greenwood Press (Westport, CT), 1977.

* (Coauthor) O'odham Creation and Related Events: As Told to Ruth Benedict, University of Arizona Press (Tucson, AZ), 2001.

Contributor to periodicals, including New York Herald Tribune. Editor of Journal of American Folklore. Contributor, under pseudonyms Ann Singleton, Ruth Stanhope, and Edgar Stanhope, of poems to periodicals, including Nation and Poetry.