Rogers Fred biography

Date of birth : 1928-03-20

Date of death : 2003-02-27

Birthplace : Latrobe, Pennsylvania, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-09-06

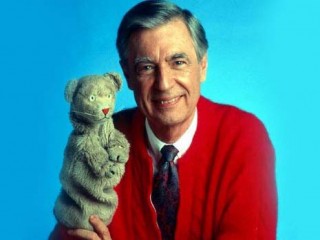

Credited as : Television show host and producer, singer and writer, hosted Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

0 votes so far

Rogers was born in Latrobe, an industrial town outside Pittsburgh, to James Hillis Rogers, who prospered as president of McFeely Brick Company, and Nancy (McFeely) Rogers. Rogers lived a solitary childhood. He was overweight, sickly, and prone to hay fever. His sheltering mother discouraged him from playing outside or interacting with other children. He amused himself by playing with puppets and learning music. He was an only child until age eleven, when his parents adopted a baby girl. Rogers would winter in Florida with Fred Brooks McFeely, his grandfather. On these annual excursions McFeely would broaden the boy’s horizons by allowing him to test his strength and develop outdoor skills, such as horseback riding, that were denied him at home. Rogers recalled that one day his grandfather told him, “There’s only one person in the world like you. And I happen to like you just the way you are.” Rogers never forgot that conversation and years later it would yield the signature line he would utter hundreds of times on television.

At Latrobe High School he edited the school newspaper and was elected student council president. He attended Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, as a Romance languages major, transferring a year later to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, where he focused on music composition. In 1951 he graduated magna cum laude with a BM from Rollins and found work in New York City in the fledging industry of television. He got a job at the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) in New York City and held technical posts on some of the shows of the era, including The Voice of Firestone, NBC Television Opera, Your Lucky Strike Hit Parade (1951–1953), and The Kate Smith Hour (1951–1953). On 9 July 1952 he married his college sweetheart from Rollins College, the concert pianist Sara Joanne Byrd, after proposing by letter. Their union would produce two sons, James and John.

Rogers was efficient and successful in his jobs, but he was consumed with a gnawing passion for another kind of television: children’s programming. In 1953 he quit NBC and took a job back in Pittsburgh, where a group was launching WQED, the nation’s first community-sponsored television station, a forerunner of modern public television. There he wrote, produced, and played the organ for an hour-long show, Children’s Corner, hosted by Josie Carey.

Among his duties for the show was as puppet master, working some personalities that would transfer ultimately to his own show—the gentle Daniel Striped Tiger, the inquisitive X the Owl, the egocentric King Friday XIII, and the caustic Lady Elaine Fairchilde. In 1955 Children’s Corner won the Sylvania Award for the nation’s best locally produced children’s program.

Rogers studied in his off-hours from WQED. He enrolled at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, earning his BD magna cum laude in 1962; he also studied early childhood development at University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Child Development. There he met and was influenced by Margaret McFarland, a child psychologist who focused on the inner lives of youngsters. In 1963 Rogers was ordained by the United Presbyterian Church with a charge to continue working with children and families through television. He developed a fifteen-minute daily children’s television program for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) called Misterogers. WQED picked it up in 1964 and the Eastern Educational Network underwrote one hundred episodes in 1965. When the funding ran out, the Sears-Roebuck Foundation offered $150,000 to continue the show and the National Educational Television network, forerunner of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), matched the amount. The series was renamed Misterogers’ Neighborhood and became Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood when adapted for the U.S. market. It launched in the United States on 19 February 1968 and was an instant hit in the three-, four-, and five-year-old demographic.

Rogers believed in predictability and routine for children, an idea reflected in the ritualized introduction to the program. Rogers would enter his living room, remove his sport coat and don a sweater, then slip into comfortable shoes. All the while he would sing the song that millions of children would count among their first: “It’s a beautiful day in this neighborhood, / A beautiful day for a neighbor. / Would you be mine? / Could you be mine? / Won’t you be my neighbor?” Then Rogers was off exploring the theme of the day, often based in childhood emotions like sadness, aggression, or fear. A revolving cast would pop in and offer perspective on the topic, people like Mr. McFeely the Speedy Delivery man, named for Rogers’s beloved grandfather. Then from the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, the puppets would offer some drama on the subject. Rogers would bid children to join him on a ride in an old-fashioned toy trolley, which carried them from real life to fantasy, a symbolic inner journey that encouraged the youngsters to suspend belief while hearing real-life lessons tailored to their development level. As time ran out, Rogers would hang up his sweater and say gently, “I like being your television neighbor.” He’d wave, smile, and walk out the door.

Rogers explored a range of topics over the years, including death, war, poverty, disability, and even divorce. He sat at the kitchen table, looked into camera, and said, “Did you ever know any grown-ups who got married and then later they got a divorce?” He went on to say he knew such a couple and their children cried, thinking it was their fault. It was not their fault, he reassured his audience, and said the topic was important to discuss with the family.

Less dire topics were addressed as straightforwardly and compassionately, like the fears some children have about being sucked down the drain of the tub or falling into a toilet. In the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks, he made a series of public service announcements to reassure children that they would be safe and cared for. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was unlike anything on television and was the apotheosis of children’s programming: it did not shout, spin, gyrate graphically, admit slapstick characters, or entertain with violence. It moved at a stately pace with silences that would be considered awkward elsewhere. It was a placid oasis, a place of threadbare puppets and plainspoken truths. Musical guests were a staple of the show, and Rogers attracted many prominent artists; Yo-Yo Ma, Itzhak Perlman, Van Cliburn, Tony Bennett, and Wynton Marsalis all appeared.

Rogers never spoke down to his audience or adopted an overbearing tone. His manner made him a target of satire, such as the skit “Mister Robinson’s Neighborhood,” a ghetto parody of the show by Eddie Murphy on Saturday Night Live in the 1980s. His gentle nature concerned some critics, who wondered whether Mr. Rogers was a good male role model. “So, I’m not John Wayne,” Rogers responded. Rogers lived by routine. He rose at five each morning, went swimming, kept his weight at 143 pounds, and went to bed each night by nine thirty. He did not smoke, drink alcohol, or eat meat. Though he was considered as square as a person could be, he was a major draw on the college circuit, where students inexplicably were eager to see their childhood friend and became caught up in emotion during his straight-on message of self-respect.

His ratings peaked in the 1985–1986 season, when he was viewed in about 8 percent of the nation’s households. By the 1999–2000 season, amid intense competition from cable networks aiming programming at children, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was viewed in fewer than 3 percent of households. The program was already the longest-running in PBS history when in 2000 he decided to quit making new episodes. The last original show aired in August 2001, though the show continued in reruns for years on some PBS affiliates, voicing the signature line inspired by grandfather McFeely: “I like you just the way you are.”

Rogers was diagnosed with stomach cancer, died in his Pittsburgh home at age seventy-four, and was entombed at Unity Cemetery near Latrobe. In his career Rogers was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom (2002), five Emmy Awards, two George Foster Peabody Radio and Television Awards, and in 1999 was inducted into the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame. One of his cardigans, a red one, hangs in the Smithsonian Institution.

Biographical information is in JoAnn DiFranco and Anthony DiFranco, Mister Rogers: Good Neighbor to America’s Children (1983). Discussion of his early life is in George E. Stanley, Mr. Rogers (2004). Rogers’s spiritual beliefs are discussed in Amy Hollingsworth, The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers: Spiritual Insights from the World’s Most Beloved Neighbor (2005). The foremost book about Rogers’s impact on children through the medium of television is his Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood: Children, Television, and Fred Rogers (1996). His philosophy is outlined in The World According to Mister Rogers: Important Things to Remember (2003). His guide to child rearing is Mister Rogers’ Parenting Book: Helping to Understand Your Young Child (2002). Obituaries are in the New York Times and Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (both 28 Feb. 2003).