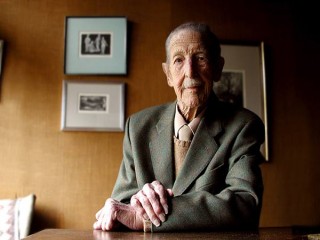

Raymond Firth biography

Date of birth : 1901-03-25

Date of death : 2002-02-22

Birthplace : Auckland, New Zealand

Nationality : New Zealand

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2010-10-13

Credited as : Anthropologist, ethnologist, study of Maori culture

1 votes so far

Life

Raymond William Firth was born on March 25, 1901, in Auckland, New Zealand, the son of Wesley and Marie Firth. Already as a boy he became acquainted with Maori culture, and had learned the Maori language. He received basic education at Auckland Grammar School, and then went on to Auckland University College, where he graduated in economics in 1921. He completed his M.A. there in 1922, with the thesis on the Kauri Gum Industry, and in 1923, received a diploma in social science. In 1924, he went to London to begin his doctoral research at the London School of Economics (LSE). He started to work on a thesis on the “frozen meat industry in New Zealand.”

However, after a chance meeting with the eminent social anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski, Firth decided to study anthropology. In his studies, he managed to combine both fields of economics and anthropology, with Pacific ethnography. During this period he started to work as research assistant to Sir James Frazer, author of The Golden Bough. Firth received his Ph.D. in 1927, with his doctoral thesis (published in 1929) entitled, Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Māori.

In 1928, he visited Tikopia, the southernmost of the Solomon Islands, to study the Polynesian culture of the local people. Thus began Firth's long-lasting relationship with around 1300 people who lived on this remote island, work which resulted in ten books and numerous articles written over many years. The first of these, We the Tikopia: A Sociological Study of Kinship in Primitive Polynesia (1936), still serves as a valuable source of information to students on Polynesian culture.

In 1930, Firth started teaching at the University of Sydney. After 18 months, however, he returned to the London School of Economics where he was appointed a lecturer in 1933, and a reader in 1935. He married Rosemary Upcott in 1936, and they had one son, Hugh, born in 1946.

In 1937, after the departure of Alfred Radcliffe-Brown from the University of Chicago, Firth took over his position as visiting professor. He also succeeded Radcliffe-Brown as acting editor of the journal Oceania, and as acting director of the Anthropology Research Committee of the Australian National Research Committee.

At the same time, he started fieldwork in Kelantan and Terengganu in Malaya in 1939-1940. When the Second World War broke out, Firth joined British naval intelligence, where he wrote and edited the four volumes of the Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series, about the Pacific Islands. During this period Firth lived in Cambridge, where the LSE had its wartime home.

In 1944, Firth succeeded Malinowski as professor of social anthropology at LSE, remaining there for the next 24 years. He visited Tikopia several more times, but due to his many other duties, remained mainly in London.

Firth retired from active work in 1968, but continued to lecture and write. He took up a year's appointment as professor of Pacific Anthropology at the University of Hawaii, and served as a visiting professor at British Columbia (1969), Cornell (1970), Chicago (1970-1), the Graduate School of the City University of New York (1971), and UC Davis (1974). He was knighted in 1973, and received the first Leverhulme Medal for a scholar of international distinction in 2002.

Firth continued with the research and was still publishing articles in his late nineties. He died in London a few weeks before his 101st birthday (his father had lived to 104).

Work

Firth spent almost his whole life studying the Maori culture. However, unlike other anthropologists who merely recorded observable facts, like settlements or rituals, Firth wanted to discover the meaning behind those external manifestations. He investigated the values of the people he studied, and the complex relationships within their society. In this sense he was the real pioneer of social anthropology, which in his time was still greatly undeveloped. At the time when British anthropology, under the leadership of Radcliffe-Brown and Evans-Pritchard, was dominated by their structural functionalism, Firth continued Malinowski's functionalist program, focusing on the role of culture in people’s lives. He was particularly interested in the role of social institutions—family, kinship, religious, and economic organizations.

In his approach to anthropology, Firth was a pioneer of economic anthropology. He believed that neoclassical principles of economics, like maximization of utility or scarcity of means, are universal and could be applied to primitive societies. His approach is regarded as belonging to formalist model of economic anthropology.

In his book from 1929, Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Maori, Firth analyzed the Maori system of land ownership and the principles of their economy. This was the first work ever written to discuss the basics of Maori economy in relationship to their culture. It also criticized colonization and the expropriation of Maori land.

Firth also spent many years on the island of Tikopia, a tiny volcanic island between Fiji and Solomon’s archipelago. By the time of his arrival, the island was practically untouched by outside people, and as such was especially valuable for anthropological study. A total of around 1300 people lived there. Firth first gathered material and compiled the first dictionary of the Tikopian language, which was quite similar to Maori. He then analyzed their family system, described in his book We, The Tikopia (1936); economic system, in Primitive Polynesian Economy (1939); values and beliefs, in The Work of the Gods in Tikopia (1940), and social structure, in Social Change in Tikopia (1959) as well as History and Traditions of Tikopia (1961).

Firth wrote extensively on the traditional religious thoughts and practices of Tikopians. When he first visited Tikopia, the 1300 inhabitants were still mostly non-Christian, although some attempts of conversion have been made earlier by Christian missionaries. Firth recorded many religious practices, and grew rather fond of them. He later wrote on the effect churches had on local people when Christian missionaries arrived. He became particularly critical of proselytizing, seeing it as a form of pressure to give up one's own identity:

[W]hat justification can be found for this steady pressure to break down the customs of a people against whom the main charge is that their gods are different from ours?” (We, the Tikopia, p.50).

During that time, Firth grew bitter toward religion. Brought up a Methodist and teaching Sunday School in his youth, Firth steadily drifted away from Christianity. By the middle of his life, his worldview turned completely toward humanistic rationalism. In his book, Social Change in Tikopia (1959), he recorded the final days of Tikopian conversion to Christianity.

By the end of his career, Firth’s work became more theoretical. He wrote on general principles of anthropology. He was known as one of leading proponents of methodological individualist movement at the London School of Economics. Firth emphasized the role of an individual in a bigger “whole,” and explained complex social forms in terms of individual people’s actions.

Legacy

Firth was professor to such students as Ernest Gellner, and others, who later become distinguished leaders in anthropology and sociology. He developed the branch of economic anthropology, which uses principles of economics to explain the dynamics within and between different cultures. Firth was also the editor of Man and Culture (1957), which has been considered one of the best works about Bronislaw Malinowski and his influence on the development of anthropology

Raymond Firth was one of the greatest experts on Maori culture. His work among the Maori, and especially Tikopians, became the groundwork for all later study of Polynesian culture. The essays he wrote back in the 1930s served for decades as the essential source of information for college students in anthropology.