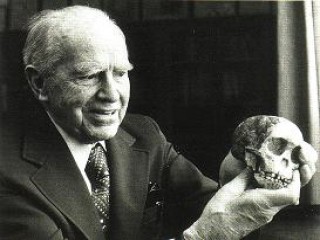

Raymond Dart biography

Date of birth : 1893-02-04

Date of death : 1988-11-22

Birthplace : Toowong, Brisbane, Australia

Nationality : American

Category : Arhitecture and Engineering

Last modified : 2010-10-14

Credited as : Anthropologist, anatomist, discovery of a fossil of Australopithecus at Taung - South Africa

1 votes so far

Life

Raymond Arthur Dart was born in Toowong, Brisbane, Australia into a family of farmers, the fifth of nine children. After receiving a scholarship and attending the Ipswich Grammar School at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, where he showed his great intelligence by winning several prizes, he continued on to study medicine at the University of Sydney.

After graduation, in the middle of World War I, Dart decided to go to England to serve in the medical corps. Then, in 1920, he enrolled at the University of London to study anatomy. At the University of London, Dart became an assistant to Grafton Elliot Smith, one of the world’s most famous neuroanatomists. Dart built his reputation as being Smith’s brightest student.

In 1922 Dart accepted a position as head of the newly established department of anatomy at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. He worked hard to organize the department from scratch.

In 1924 Dart excavated fossil bones of what later became known as the "Taung baby" or "Taung Child." He named it Australopithecus africanus, or Southern ape from Africa, publishing this find in an article in Nature. The discovery was initially praised in the scientific community as the "missing link" between apes and humans, but later was rejected as simply an ape. In 1930 Dart traveled to London to defend his position, but found little support.

Dart returned to Witwaterrand and continued to focus on his work in the anatomy department. He served there as dean from 1925 to 1943. He married twice and had two children.

In the mid-1940s, Dart started new excavations at Makapansgat, discovering evidence suggesting Australopithecines had knowledge of fire-making and that they were fierce savage hunters. The myth of the “killer ape” was perpetuated and popularized through books such as African Genesis by R. Ardrey, although scientists later refuted the evidence. In the late 1940s, however, scientists accepted the hominid nature of Australopithecus, saving Dart’s name from oblivion.

Dart continued to teach at the University of Johannesburg until 1958. He died in 1988, at the age of 95.

Work

Besides his work in the Anatomy department at the University of Johannesburg, Dart’s contributions to science were significant, albeit controversial, discoveries of Australopithecus fossils, including that of the "Taung Child."

Although initially well-received and generating much excitement as a possible "missing link," Dart's find was subsequently rejected by scientists. Therefore, in the mid-1940s, Dart started new excavations at Makapansgat. He found numerous blackened bones that indicated the possibility that Australopithecus had knowledge of fire-making, and named the species Australopithecus prometheus.

Based on his examination of various bones, Dart concluded that Australopithecus africanus could walk upright, and possibly used tools. Controversy arose around the usage of tools, as some scientists claimed that Australopithecus used bones of antelopes and wild boars as tools, while others argued that those bones were only remains of food that they ate. When, in the late 1940s, Robert Broom and Wilfrid Le Gros Clark discovered further australopithecines, this eventually vindicated Dart. So much so that in 1947, Sir Arthur Keith said "...Dart was right, and I was wrong."

The name "Taung Child" refers to the fossil of a skull specimen of Australopithecus africanus. It was discovered in 1924 by a quarryman working for the Northern Lime Company in Taung, South Africa. Dart immediately recognized its importance and published his discovery in the journal Nature in 1925, describing it as a new species. The scientific community was initially very interested in this find. However, due to the Piltdown man hoax, consisting of fossilized fragments indicating a large brain and ape-like teeth—the exact opposite of the Taung Child, Dart's finding was not appreciated for decades.

Dart's discovery and Dart himself came under heavy criticism by the eminent anthropologists of the day, most notably Sir Arthur Keith, who claimed the "Taung Child" to be nothing other than a juvenile gorilla. Since the specimen was indeed a juvenile, there was room for interpretation, and because African origins for humankind and the development of bipedalism before a human-like brain were both inconsistent with the prevailing evolutionary notions of the time, Dart and his "Child" were subject to ridicule.

Based on subsequent evidence from "Turkana Boy," discovered in 1984 by Kamoya Kimeu, a member of a team led by Richard Leakey, at Nariokotome near Lake Turkana in Kenya, scientists came to believe that Taung Child was a three-year-old being, standing three feet, six inches tall and weighing approximately 75 pounds at the time of its death 2.5 million years ago.

Research on Taung Child continued after Dart's death. In early 2006, it was announced that the Taung Child was likely killed by an eagle, or similar large predatory bird. This conclusion was reached by noting similarities in the damage to the skull and eye sockets of the Taung Child to the skulls of primates known to have been killed by eagles (Berger 2006).

As of 2006, the skull has been exhibited at the Maropeng visitor's center at the "Cradle of Humankind" in Gauteng, South Africa.

Legacy

The significance of Dart’s work lies in the fact that Taung Child was the first fossil of an early human relative, found in Africa—just as Darwin had predicted. Subsequent research, such as "Mrs. Ples" discovered in 1947 at Sterkfontein in South Africa by paleontologist, Robert Broom who was Dart's only early supporter, and later discoveries by Louis Leakey, Mary Leakey, and Richard Leakey at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and Turkana in Kenya, added to Dart's discoveries of Australopithecines, and established Africa as the site of the origin of the human race.

Phillip Tobias continued Dart’s work and has contributed to the study of the "Cradle of Humanity." The Institute for the Study of Man in Africa was founded at Witwatersrand in Dart’s honor.