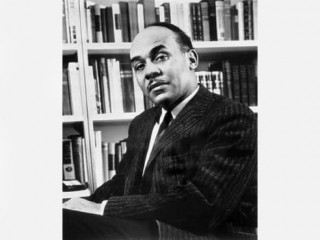

Ralph Waldo Ellison biography

Date of birth : 1914-03-01

Date of death : 1994-04-16

Birthplace : Oklahoma, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-07-13

Credited as : Fiction writer, ,

1 votes so far

"Sidelights"

Growing up in Oklahoma, a "frontier" state that "had no tradition of slavery" and where "relationships between the races were more fluid and thus more human than in the old slave states," Ralph Ellison became conscious of his obligation "to explore the full range of American Negro humanity and to affirm those qualities which are of value beyond any question of segregation, economics or previous condition of servitude." This sense of obligation, articulated in his 1964 collection of critical and biographical essays, Shadow and Act, led to his staunch refusal to limit his artistic vision to the "uneasy sanctuary of race" and commit instead to a literature that explores and affirms the complex, often contradictory frontier of an identity at once black and American and universally human. For Ellison, whom John F. Callahan in a Chant of Saints: A Gathering of Afro-American Literature, Art, and Scholarship essay called a "moral historian," the act of writing was fraught with both great possibility and grave responsibility. As Ellison asserted, writing "offers me the possibility of contributing not only to the growth of the literature but to the shaping of the culture as I should like it to be. The American novel is in this sense a conquest of the frontier; as it describes our experience, it creates it."

For Ellison, then, the task of the novelist was a moral and political one. In his preface to the thirtieth anniversary edition of Invisible Man, Ellison argued that the serious novel, like the best politics, "is a thrust toward a human ideal." Even when the ideal is not realized in the actual, he declared, "there is still available that fictional vision of an ideal democracy in which the actual combines with the ideal and gives us representations of a state of things in which the highly placed and the lowly, the black and the white, the Northerner and the Southerner, the native-born and the immigrant are combined to tell us of transcendent truths and possibilities such as those discovered when Mark Twain set Huck and Jim afloat on the raft." Ellison saw the novel as a "raft of hope" that may help readers stay above water as they try "to negotiate the snags and whirlpools that mark our nation's vacillating course toward and away from the democratic ideal."

Early in his career, Ellison conceived of his vocation as a musician, as a composer of symphonies. When he entered Alabama's Tuskegee Institute in 1933 he enrolled as a music major; he wonders in Shadow and Act if he did so because, given his background, it was the only art "that seemed to offer some possibility for self-definition." The act of writing soon presented itself as an art through which he could link the disparate worlds he cherished, could verbally record and create the "affirmation of Negro life" he knew was so intrinsic a part of the universally human. To move beyond the old definitions that separated jazz from classical music, vernacular from literary language, the folk from the mythic, he would have to discover a prose style that could equal the integrative imagination of the "Renaissance Man."

Because Ellison did not get a job that paid him enough to save money for tuition, he stayed in New York, working and studying composition until his mother died in Dayton, Ohio. After his return to Dayton, he and his brother supported themselves by hunting. Though Ellison had hunted for years, he did not know how to wing-shoot; it was from Hemingway's fiction that he learned this process. Ellison studied Hemingway to learn writing techniques; from the older writer he also learned a lesson in descriptive accuracy and power, in the close relationship between fiction and reality. Like his narrator in Invisible Man, Ellison did not return to college; instead he began his long apprenticeship as a writer, his long and often difficult journey toward self-definition.

Ellison's early days in New York, before his return to Dayton, provided him with experiences that would later translate themselves into his theory of fiction. Two days after his arrival in "deceptively `free' Harlem," he met black poet Langston Hughes who introduced him to the works of Andre Malraux, a French writer defined as Marxist. Though attracted to Marxism, Ellison sensed in Malraux something beyond a simplistic political sense of the human condition. Said Ellison: Malraux "was the artist-revolutionary rather than a politician when he wrote Man's Fate, and the book lives not because of a political position embraced at the time, but because of its larger concern with the tragic struggle of humanity." Ellison began to form his definition of the artist as a revolutionary concerned less with local injustice than with the timelessly tragic.

Ellison's view of art was furthered after he met black novelist Richard Wright. Wright urged him to read Joseph Conrad, Henry James, James Joyce, and Feodor Dostoevsky and invited Ellison to contribute a review essay and then a short story to the magazine he was editing. Wright was then in the process of writing Native Son, much of which Ellison read, he declared in Shadow and Act, "as it came out of the typewriter." Though awed by the process of writing and aware of the achievement of the novel, Ellison, who had just read Malraux, began to form his objections to the "sociological," deterministic ideology which informed the portrait of the work's protagonist, Bigger Thomas. In Shadow and Act, which Arthur P. Davis in From the Dark Tower: Afro-American Writers, 1900 to 1960 described as partly an apologia provita sua (a defense of his life), Ellison articulated the basis of his objection: "I, for instance, found it disturbing that Bigger Thomas had none of the finer qualities of Richard Wright, none of the imagination, none of the sense of poetry, none of the gaiety." Ellison thus refuted the depiction of the black individual as an inarticulate victim whose life is one only of despair, anger, and pain. He insisted that art must capture instead the complex reality, the pain and the pleasure of black existence, thereby challenging the definition of the black person as something less than fully human. Such a vision of art, which is at the heart of Invisible Man, became the focal point of an extended debate between Ellison and Irving Howe, who in a 1963 Dissent article accused Ellison of disloyalty to Wright in particular and to "protest fiction" in general.

From 1938 to 1944, Ellison published a number of short stories and contributed essays to journals such as New Masses. As with other examples of Ellison's work, these stories have provoked disparate readings. In an essay in Black World, Ernest Kaiser called the earliest stories and the essays in New Masses "the healthiest" of Ellison's career. The critic praised the economic theories that inform the early fiction, and he found Ellison's language pure, emotional, and effective. Lamenting a change he attributed to Ellison's concern with literary technique, Kaiser charged the later stories, essays, and novels with being no longer concerned with people's problems and with being "unemotional." Other critics, like Marcus Klein in After Alienation: American Novels in Mid-Century, saw the early work as a progressive preparation for Ellison's mature fiction and theory. In the earliest of these stories, "Slick Gonna Learn," Ellison drew a character shaped largely by an ideological, naturalistic conception of existence, the very type of character he later repudiated. From this imitation of proletarian fiction, Ellison's work moved towards psychological and finally metaphysical explorations of the human condition. His characters thus were freed from restrictive definitions as Ellison developed a voice that was his own, Klein maintains.

In the two latest stories of the 1938-1944 period, "Flying Home" and "King of the Bingo Game," Ellison created characters congruent with his sense of pluralism and possibility and does so in a narrative style that begins to approach the complexity of Invisible Man. As Arthur P. Davis noted, in "Flying Home" Ellison combined realism, folk story, symbolism, and a touch of surrealism to present his protagonist, Todd. In a fictional world composed of myriad levels of the mythic and the folk, the classical and the modern, Todd fights to free himself of imposed definitions. In "King of the Bingo Game," Ellison experimented with integrating sources and techniques. As in all of Ellison's early stories, the protagonist is a young black man fighting for his freedom against forces and people that attempt to deny it. In "King of the Bingo Game," Robert G. O'Meally argued in The Craft of Ralph Ellison, "the struggle is seen in its most abstracted form." This abstraction results from the "dreamlike shifts of time and levels of consciousness" that dominate the surrealistic story and also from the fact that "the King is Ellison's first character to sense the frightening absurdity of everyday American life." In an epiphany which frees him from illusion and which places him, even if for only a moment, in control, the King realizes "that his battle for freedom and identity must be waged not against individuals or even groups, but against no less than history and fate," O'Meally declared. The parameters of the fight for freedom and identity have been broadened. Ellison saw his black hero as one who wages the oldest battle in human history: the fight for freedom to be timelessly human, to engage in the "tragic struggle of humanity," as the writer asserted in Shadow and Act.

Whereas The King achieves awareness for a moment, the Invisible Man not only becomes aware but is able to articulate fully the struggle. As Ellison noted in his preface to the anniversary edition of the novel, too often characters have been "figures caught up in the most intense forms of social struggle, subject to the most extreme forms of the human predicament but yet seldom able to articulate the issues which tortured them." The Invisible Man is endowed with eloquence; he is Ellison's radical experiment with a fiction that insists upon the full range and humanity of the black character.

Ellison began Invisible Man in 1945. Although he was at work on a never-completed war novel at the time, Ellison recalled in his 1982 preface that he could not ignore the "taunting, disembodied voice" he heard beckoning him to write Invisible Man. Published in 1952 after a seven-year creative struggle, and awarded the National Book Award in 1953, Invisible Man received critical acclaim. Although some early reviewers were puzzled or disappointed by the experimental narrative techniques, many now agree that these techniques give the work its lasting force and account for Ellison's influence on later fiction. The novel is a fugue of cultural fragments--echoes of Homer, Joyce, Eliot, and Hemingway join forces with the sounds of spirituals, blues, jazz, and nursery rhymes. The Invisible Man is as haunted by Louis Armstrong's "What did I do / To be so black / And blue?" as he is by Hemingway's bullfight scenes and his matadors' grace under pressure. The linking together of these disparate cultural elements allows the Invisible Man to draw the portrait of his inner face that is the way out of his wasteland.

In the novel, Ellison clearly employed the traditional motif of the Bildungsroman, or novel of education: the Invisible Man moves from innocence to experience, darkness to light, from blindness to sight. Complicating this linear journey, however, is the narrative frame provided by the Prologue and Epilogue which the narrator composes after the completion of his above-ground educational journey. Yet readers begin with the Prologue, written in his underground chamber on the "border area" of Harlem where he is waging a guerrilla war against the Monopolated Light & Power Company by invisibly draining their power. At first denied the story of his discovery, readers must be initiated through the act of re-experiencing the events that led them and the narrator to this hole. Armed with some suggestive hints and symbols, readers then start the journey toward a revisioning of the Invisible Man, America, and themselves.

The act of writing, of ordering and defining the self, is what gives the Invisible Man freedom and what allows him to manage the absurdity and chaos of everyday life. Writing frees the self from imposed definitions, from the straitjacket of all that would limit the productive possibilities of the self. Echoing the pluralism of the novel's form, the Invisible Man insists on the freedom to be ambivalent, to love and to hate, to denounce and to defend the America he inherits. Ellison himself was well-acquainted with the ambivalence of his American heritage; nowhere is it more evident than in his name. Named after the nineteenth-century essayist and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, whom Ellison's father admired, the name created for Ellison embarrassment, confusion, and a desire to be the American writer his namesake called for. And Ellison placed such emphasis on his unnamed yet self-named narrator's breaking the shackles of restrictive definitions, of what others call reality or right, he also freed himself, as Robert B. Stepto in From Behind the Veil: A Study of Afro-American Narrative argued, from the strictures of the traditional slave narratives of Frederick Douglas and W. E. B. Du Bois. By consciously invoking this form but then not bringing the motif of "ascent and immersion" to its traditional completion, Ellison revoiced the form, made it his own, and stepped outside it.

In her 1979 PMLA essay, Susan Blake argued that Ellison's insistence that black experience be ritualized as part of the larger human experience results in a denial of the unique social reality of black life. Because Ellison so thoroughly adapted black folklore into the Western tradition, Blake found that the definition of black life becomes "not black but white"; it "exchanges the self-definition of the folk for the definition of the masters." Thorpe Butler, in a 1984 College Language Association Journal essay, defended Ellison against Blake's criticism. He declared that Ellison's depiction of specific black experience as part of the universal does not "diminish the unique richness and anguish" of that experience and does not "diminish the force of Ellison's protest against the blind, cruel dehumanization of black Americans by white society." This debate extends arguments that have appeared since the publication of the novel. Underlying these controversies is the old, uneasy argument about the relationship of art and politics, of literary practice and social commitment.

Although the search for identity is the major theme of Invisible Man, other aspects of the novel have also received critical attention. Among them, as Joanne Giza noted in her essay in Black American Writers: Bibliographical Essays, are literary debts and analogies, comic elements, the metaphor of vision, use of the blues, and folkloric elements. Although all of these concerns are part of the larger issue of identity, Ellison's use of blues and folklore has been singled out as a major contribution to contemporary literature and culture. Since the publication of Invisible Man, scores of articles have appeared on these two topics, a fact which in turn has led to a rediscovery and revisioning of the importance of blues and folklore to American literature and culture in general.

Much of Ellison's groundbreaking work is presented in Shadow and Act. Published in 1964, this collection of essays, said Ellison, is "concerned with three general themes: with literature and folklore, with Negro musical expression--especially jazz and the blues--and with the complex relationship between the Negro American subculture and North American culture as a whole." This volume has been hailed as one of the more prominent examples of cultural criticism of the century. Writing in Commentary, Robert Penn Warren praised the astuteness of Ellison's perceptions; in New Leader, Stanley Edgar Hyman proclaimed Ellison "the profoundest cultural critic we have." In the New York Review of Books, R. W. B. Lewis explored Ellison's study of black music as a form of power and found that "Ellison is not only a self-identifier but the source of self-definition in others." Published in 1986, Going to the Territory is a second collection of essays reprising many of the subjects and concerns treated in Shadow and Act--literature, art, music, the relationships of black and white cultures, fragments of autobiography, tributes to such noted black Americans as Richard Wright, Duke Ellington, and painter Romare Beardon. With the exception of "An Extravagance of Laughter," a lengthy examination of Ellison's response to Jack Kirkland's dramatization of Erskine Caldwell's novel Tobacco Road, the essays in Going to the Territory are reprints of previously published articles or speeches, most of them dating from the 1960s.

Ellison's influence as both novelist and critic, as artist and cultural historian, has been enormous. In special issues of Black World and College Language Association Journal devoted to Ellison, strident attacks appear alongside equally spirited accolades. Perhaps another measure of Ellison's stature and achievement was his readers' vigil for his long-awaited second novel. Although Ellison often refused to answer questions about the work-in-progress, there was enough evidence during Ellison's lifetime to suggest that the manuscript was very large, that all or part of it was destroyed in a fire and was being rewritten, and that its creation was a long and painful task. Most readers waited expectantly, believing that Ellison, who said in Shadow and Act that he "failed of eloquence" in Invisible Man, intended to wait until his second novel equaled his imaginative vision of the American novel as conqueror of the frontier, equaled the Emersonian call for a literature to release all people from the bonds of oppression.

Eight excerpts from this novel-in-progress were originally published in journals such as Quarterly Review of Literature, Massachusetts Review, and Noble Savage. Set in the South in the years spanning the Jazz Age to the Civil Rights movement, these fragments seemed an attempt to recreate modern American history and identity. The major characters are the Reverend Hickman, a one-time jazz musician, and Bliss, the light-skinned boy whom he adopts and who later passes into white society and becomes Senator Sunraider, an advocate of white supremacy. As O'Meally noted in The Craft of Ralph Ellison, the major difference between Bliss and Ellison's earlier young protagonists is that despite some harsh collisions with reality, Bliss refuses to divest himself of his illusions and accept his personal history. Said O'Meally: "Moreover, it is a renunciation of the blackness of American experience and culture, a refusal to accept the American past in all its complexity."

After Ellison's death on April 16, 1994, speculation about the existence of the second novel reignited. In an article in the New York Times, William Grimes assembled the information available on the subject. "Joe Fox, Mr. Ellison's editor at Random House, and close friends of the novelist say that Mr. Ellison has left a manuscript of somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 pages," Grimes reported. "At the time of his death, he had been working on it every day and was close to completing the work, whose fate now rests with his widow, Fanny." A close friend of Ellison's, John F. Callahan, a college dean from Portland, Oregon, told Grimes that he had seen parts of the manuscript not already published in other sources. "From what I've read, if Invisible Man is akin to Joyce's Portrait of the Artist, then the novel in progress may be his Ulysses." Callahan added that "it's a weaving together of all kinds of voices, and not simply voices in the black tradition, but white voices, too: all kinds of American voices." As Grimes suggested, "If Mr. Ellison, as his final creative act, were to top Invisible Man, it would be a stunning bequest," given that the first novel is considered a literary classic. Invisible Man "has never been out of print," Grimes pointed out. "It has sold millions of copies worldwide. On college campuses it is required reading in twentieth-century American literature courses, and it has been the subject of hundreds of scholarly articles."

In 1999, five years after his death, the longtime rumors surrounding this second novel were finally answered--at least in part--with the publication of Juneteenth. The novel was culled from Ellison's voluminous manuscript by Callahan, who became Ellison's literary executor after the author's death. According to Callahan, the published form of Juneteenth consists of several distinct elements: a 1959 published story titled "And Hickman Arrives"; one of three long narratives (referred to as "Book 2" in Ellison's notes) in the novel that Ellison had been working on for years before he died; a thirty-eight page draft titled "Bliss's Birth"; and a single paragraph from a short fictional piece titled "Cadillac Flambe." The chief characters remain the same as those from the earlier published excerpts: the white, race-baiting Senator Sunraider (also called "Bliss") and the black minister Alonzo Hickman, who raised Bliss as a child. The novel's action is set in motion via a visit by Hickman to the Senate chambers to hear Bliss speak. During the speech, Bliss is mortally wounded by a gunman, and the remainder of the novel features a dying Bliss and a watchful Hickman--the only person whom Bliss allows to see him--reminiscing about their earlier relationship. Much like Invisible Man, the novel addresses such themes as the black-white divide in America; the nature of identity; and the interaction between politics and religion. The novel's title, in fact, comes from a combined religious/political holiday celebrated by African Americans to commemorate a day in June 1865, when black slaves in Texas finally discovered that they were free--more than two years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

Given the unusual circumstances of the book's publication, reviewers perhaps inevitably focused as much on these circumstances as on the merits of the work itself. Specifically, critics focused on Callahan's role in shaping a single narrative out of Ellison's sprawling manuscript despite the lack of any instructions from the author himself about what he intended the novel to be. Lamenting that Callahan had excised two of the three narratives that made up Ellison's manuscript, New York Times Book Review contributor Louis Menand noted, "It seems unfair to Ellison to review a novel he did not write. . . . A three-part work implies counterpoint: whatever appears in a Book 2 must be designed to derive its novelistic significance from whatever would have appeared in a Book 1 and a Book 3." According to Gerald Early in the Chicago Tribune Books, the new work "reads very much like the pastiche it is, with uneven characterization, clashing styles of writing and shifting points of view, and a jumbled narrative. The reader should be warned that this is a very unfinished product." Some reviewers reserved praise for certain prose sections that reflect Ellison's dazzling technical ability; Early, for instance, remarked on the "passages of affecting, sometimes tour-de-force writing and some deft wordplay," while a Publishers Weekly reviewer commented that the book's "flashbacks showcase Ellison's stylized set pieces, among the best scenes he has written." In the end, though, critics expressed reservations that the book should ever have been released. Menand concluded forcefully, "This is not Ralph Ellison's second novel," while Early averred that "I wonder if the world and Ralph Ellison have been best served by the publication of this work." Despite these concerns, critics noted that Ellison's literary reputation--relying heavily on the landmark Invisible Man--remains secure.

PERSONAL INFORMATION,/b>

Family: Born March 1, 1914, in Oklahoma City, OK; died of cancer, April 16, 1994, in New York, NY; son of Lewis Alfred (a construction worker and tradesman) and Ida (Millsap) Ellison; married Fanny McConnell, July, 1946. Education: Attended Tuskegee Institute, 1933-36. Avocational Interests: Jazz and classical music, photography, electronics, furniture-making, bird-watching, gardening. Military/Wartime Service: U.S. Merchant Marine, World War II. Memberships: PEN (vice president, 1964), Authors Guild, Authors League of America, American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, Institute of Jazz Studies (member of board of advisors), Century Association (resident member).

AWARDS

Rosenwald grant, 1945; National Book Award and National Newspaper Publishers' Russwurm Award, both 1953, both for Invisible Man; Certificate of Award, Chicago Defender, 1953; Rockefeller Foundation award, 1954; Prix de Rome fellowships, American Academy of Arts and Letters, 1955 and 1956; Invisible Man selected as the most distinguished postwar American novel and Ellison as the sixth most influential novelist by New York Herald Tribune Book Week poll of two hundred authors, editors, and critics, 1965; recipient of award honoring well-known Oklahomans in the arts from governor of Oklahoma, 1966; Medal of Freedom, 1969; Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et Lettres (France), 1970; Ralph Ellison Public Library, Oklahoma City, named in his honor, 1975; National Medal of Arts, 1985, for Invisible Man and for his teaching at numerous universities; honorary doctorates from Tuskegee Institute, 1963, Rutgers University, 1966, Grinnell College, 1967, University of Michigan, 1967, Williams College, 1970, Long Island University, 1971, Adelphi University, 1971, College of William and Mary, 1972, Harvard University, 1974, Wake Forest College, 1974, University of Maryland, 1974, Bard College, 1978, Wesleyan University, 1980, and Brown University, 1980.

CAREER

Writer, 1937-94. Worked as a researcher and writer on Federal Writers' Project in New York City, 1938-42; edited Negro Quarterly, 1942; lecture tour in Germany, 1954; lecturer at Salzburg Seminar, Austria, fall, 1954; U.S. Information Agency, tour of Italian cities, 1956; Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, instructor in Russian and American literature, 1958-61; New York University, New York City, Albert Schweitzer Professor in Humanities, 1970-79, professor emeritus, 1979-94. Alexander White Visiting Professor, University of Chicago, 1961; visiting professor of writing, Rutgers University, 1962-64; visiting fellow in American studies, Yale University, 1966. Gertrude Whittall Lecturer, Library of Congress, January, 1964; delivered Ewing Lectures at University of California, Los Angeles, April, 1964. Lecturer in African-American culture, folklore, and creative writing at other colleges and universities throughout the United States, including Columbia University, Fisk University, Princeton University, Antioch University, and Bennington College.Member of Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, 1966-67; honorary consultant in American letters, Library of Congress, 1966-72. Trustee, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, 1967-77, Educational Broadcasting Corp., 1968-69, New School for Social Research, 1969-83, Bennington College, 1970-75, and Museum of the City of New York, 1970-86. Charter member of National Council of the Arts, 1965-67, and of National Advisory Council, Hampshire College.

WRITINGS BY THE AUTHOR:

* Invisible Man (novel), Random House (New York City), 1952, published in a limited edition with illustrations by Steven H. Stroud, Franklin Library, 1980, thirtieth-anniversary edition with new introduction by author, Random House, 1982, edited and with an introduction by Harold Bloom, Chelsea House (New York City), 1996.

* (Author of introduction) Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage and Four Great Stories, Dell (New York City), 1960.

* Shadow and Act (essays), Random House, 1964.

* (With Karl Shapiro) The Writer's Experience (lectures; includes "Hidden Names and Complex Fate: A Writer's Experience in the U.S.," by Ellison, and "American Poet?," by Shapiro), Gertrude Clarke Whittall Poetry and Literature Fund for Library of Congress, 1964.

* (With Whitney M. Young and Herbert Gans) The City in Crisis, introduction by Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph Education Fund, 1968.

* (Author of introduction) Romare Bearden, Paintings and Projections (catalogue of exhibition, November 25-December 22, 1968), State University of New York at Albany, 1968.

* (Author of foreword) Leon Forrest, There Is a Tree More Ancient than Eden, Random House, 1973.

* Going to the Territory (essays), Random House, 1986.

* The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison, Modern Library, 1995.

* Flying Home and Other Stories, edited by John F. Callahan, preface by Saul Bellow, Random House (New York City), 1996.

* Juneteenth (novel), edited by Callahan, Random House, 1999.

OTHER

* Ralph Ellison: An Interview with the Author of Invisible Man (sound recording), Center for Cassette Studies, 1974.

* (With William Styron and James Baldwin) Is the Novel Dead?: Ellison, Styron and Baldwin on Contemporary Fiction (sound recording), Center for Cassette Studies, 1974.

* Conversations with Ralph Ellison, edited by Maryemma Graham and Amritjit Singh, University Press of Mississippi (Jackson), 1995.

* Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, edited by Albert Murray and John F. Callahan, Modern Library, 2000.