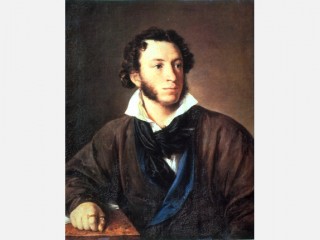

Pushkin Aleksandr biography

Date of birth : 1799-05-26

Date of death : 1837-01-29

Birthplace : Moscow, Russia

Nationality : Russian

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-04-26

Credited as : Russian poet, founder of modern Russian literature, Catherine the Great

1 votes so far

In 1811 he was selected to be among the thirty students in the first class at the Lyceum in Tsarskoe Selo . He attended the Lyceum from 1811 to 1817 and received the best education available in Russia at the time. He soon not only became the unofficial laureate of the Lyceum, but found a wider audience and recognition. He was first published in the journal The Messenger of Europe in 1814. In 1815 his poem “Recollections in Tsarskoe Selo” met the approval of Derzhavin, a great eighteenth-century poet, at a public examination in the Lyceum.

After graduating from the Lyceum, he was given a sinecure in the Collegium of Foreign Affairs in Petersburg. The next three years he spent mainly in carefree, light-hearted pursuit of pleasure. He was warmly received in literary circles; in circles of Guard-style lovers of wine, women, and song; and in groups where political liberals debated reforms and constitutions. Between 1817 and 1820 he reflected liberal views in “revolutionary” poems, his ode “Freedom,” “The Village,” and a number of poems on Aleksandr I and his minister Arakcheev. At the same time he was working on his first large-scale work, Ruslan and Liudmila.

In April 1820, his political poems led to an interrogation by the Petersburg governor-general and then to exile to South Russia, under the guise of an administrative transfer in the service. Pushkin left Petersburg for Ekaterinoslave on May 6, 1820. Soon after his arrival there he traveled around the Caucasus and the Crimea with the family of General Raevsky. During almost three years in Kishinev, Pushkin wrote his first Byronic verse tales, “The Prisoner of the Caucasus” (1820-1821), “The Bandit Brothers (1821-1822), and “The Fountain of Bakhchisaray” (1821-1823). He also wrote “Gavriiliada” (1821), a light approach to the Annunciation, and he started his novel in verse, Eugene Onegin (1823-1831).

With the aid of influential friends, he was transferred in July 1823 to Odessa, where he engaged in theatre going, social outings, and love affairs with two married women. His literary creativeness also continued, as he completed “The Fountain of Bakhchisaray” and the first chapter of Eugene Onegin, and began “The Gypsies.” After postal officials intercepted a letter in which he wrote a thinly-veiled support of atheism, Pushkin was exiled to his mother’s estate of Mikhaylovskoe in north Russia.

The next two years, from August 1824 to August 1826 he spent at Mikhaylovskoe in exile and under surveillance. However unpleasant Pushkin my have found his virtual imprisonment in the village, he continued his literary productiveness there. During 1824 and 1825 at Mikhaylovskoe he finished “The Gypsies,” wrote Boris Godunov , “Graf Nulin” and the second chapter of Eugene Onegin.

When the Decembrist Uprising took place in Petersburg on December 14, 1825, Pushkin, still in Makhaylovskoe, was not a participant. But he soon learned that he was implicated, for all the Decembrists had copies of his early political poems. He destroyed his papers that might be dangerous for himself or others. In late spring of 1826, he sent the Tsar a petition that he be released from exile. After an investigation that showed Pushkin had been behaving himself, he was summoned to leave immediately for an audience with Nicholas I. On September 8, still grimy from the road, he was taken in to see Nicholas. At the end of the interview, Pushkin was jubilant that he was now released from exile and that Nicholas I had undertaken to be the personal censor of his works.

Pushkin thought that he would be free to travel as he wished, that he could freely participate in the publication of journals, and that he would be totally free of censorship, except in cases which he himself might consider questionable and wish to refer to his royal censor. He soon found out otherwise. Count Benkendorf, Chief of Gendarmes, let Pushkin know that without advance permission he was not to make any trip, participate in any journal, or publish — or even read in literary circles — any work. He gradually discovered that he had to account for every word and action, like a naughty child or a parolee. Several times he was questioned by the police about poems he had written.

The youthful Pushkin had been a light-hearted scoffer at the state of matrimony, but freed from exile, he spent the years from 1826 to his marriage in 1831 largely in search of a wife and in preparing to settle down. He sought no less than the most beautiful woman in Russia for his bride. In 1829 he found her in Natalia Goncharova, and presented a formal proposal in April of that year. She finally agreed to marry him on the condition that his ambiguous situation with the government be clarified, which it was. As a kind of wedding present, Pushkin was given permission to publish Boris Godunov — after four years of waiting for authorization — under his “own responsibility.” He was formally betrothed on May 6, 1830.

Financial arrangements in connection with his father’s wedding gift to him of half the estate of Kistenevo necessitated a visit to the neighboring estate of Boldino, in east-central Russia. When Pushkin arrived there in September 1830, he expected to remain only a few days; however, for three whole months he was held in quarantine by an epidemic of Asiatic cholera. These three months in Boldino turned out to be literarily the most productive of his life. During the last months of his exile at Mikhaylovskoe, he had completed Chapters V and VI of Eugene Onegin, but in the four subsequent years he had written, of major works, only “Poltava”(1828), his unfinished novel The Blackamoor of Peter the Great (1827) and Chapter VII of Eugene Onegin (1827-1828). During the autumn at Boldino, Pushkin wrote the five short stories of The Tales of Belkin; the verse tale “The Little House in Kolomna;” his little tragedies, “The Avaricious Knight,” “Mozart and Salieri;” “The Stone Guest;” and “Feast in the Time of the Plague;” “The Tale of the Priest and His Workman Balda,” the first of his fairy tales in verse; the last chapter of Eugene Onegin; and “The Devils,” among other lyrics.

Pushkin was married to Natalia Goncharova on February 18, 1831, in Moscow. In May, after a honeymoon made disagreeable by “Moscow aunties” and in-laws, the Pushkins moved to Tsarskoe Selo, in order to live near the capital, but inexpensively and in “inspirational solitude and in the circle of sweet recollections.” These expectations were defeated when the cholera epidemic in Petersburg caused the Tsar and the court to take refuge in July in Tsarskoe Selo. In October 1831 the Pushkins moved to an apartment in Petersburg, where they lived for the remainder of his life. He and his wife became henceforth inextricably involved with favors from the Tsar and with court society. Mme. Pushkina’s beauty immediately made a sensation in society, and her admirers included the Tsar himself. On December 30, 1833, Nicholas I made Pushkin a Kammerjunker, an intermediate court rank usually granted at the time to youths of high aristocratic families. Pushkin was deeply offended, all the more because he was convinced that it was conferred, not for any quality of his own, but only to make it proper for the beautiful Mme. Pushkina to attend court balls. Dancing at one of these balls was followed in March 1834 by her having a miscarriage. While she was convalescing in the provinces, Pushkin spoke openly in letters to her of his indignation and humiliation. The letters were intercepted and sent to the police and to the Tsar. When Pushkin discovered this, in fury he submitted his resignation from the service on June 25, 1834. However, he had reason to fear the worst from the Tsar’s displeasure at this action, and he felt obliged to retract his resignation.

Pushkin could ill afford the expense of gowns for Mme. Pushkina for court balls or the time required for performing court duties. His woes further increased when her two unmarried sisters came in autumn 1834 to live henceforth with them. In addition, in the spring of 1834 he had taken over the management of his improvident father’s estate and had undertaken to settle the debts of his heedless brother. The result was endless cares, annoyances, and even outlays from his own pocket. He came to be in such financial straits that he applied for a leave of absence to retire to the country for three or four years, or if that were refused, for a substantial sum as loan to cover his most pressing debts and for the permission to publish a journal. The leave of absence was brusquely refused, but a loan of thirty thousand rubles was, after some trouble, negotiated; permission to publish, beginning in 1836, a quarterly literary journal, The Contemporary, was finally granted as well. The journal was not a financial success, and it involved him in endless editorial and financial cares and in difficulties with the censors, for it gave importantly placed enemies among them the opportunity to pay him off. Short visits to the country in 1834 and 1835 resulted in the completion of only one major work, “The Tale of the Golden Cockerel”(1834), and during 1836 he only completed his novel on Pugachev, The Captain’s Daughter, and a number of his finest lyrics.

Meanwhile, Mme. Pushkina loved the attention which her beauty attracted in the highest society; she was fond of “coquetting” and of being surrounded by admirers, who included the Tsar himself. In 1834 Mme. Pushkina met a young man who was not content with coquetry, a handsome French royalist ÃÅ migrÃÅ in Russian service, who was adopted by the Dutch ambassador, Heeckeren. Young d’Anthes-Heeckeren pursued Mme. Pushkina for two years, and finally so openly and unabashedly that by autumn 1836, it was becoming a scandal. On November 4, 1836 Pushkin received several copies of a “certificate” nominating him “Coadjutor of the International Order of Cuckolds.” Pushkin immediately challenged d’Anthes; at the same time, he made desperate efforts to settle his indebtedness to the Treasury. Pushkin twice allowed postponements of the duel, and then retracted the challenge when he learned “from public rumour” that d’Anthes was “really” in love with Mme. Pushkina’s sister, Ekaterina Goncharova. On January 10, 1837, the marriage took place, contrary to Pushkin’s expectations. Pushkin refused to attend the wedding or to receive the couple in his home, but in society d’Anthes pursued Mme. Pushkina even more openly. Then d’Anthes arranged a meeting with her, by persuading her friend Idalia Poletika to invite Mme. Pushkina for a visit; Mme. Poletika left the two alone, but one of her children came in, and Mme. Pushkina managed to get away. Upon hearing of this meeting, Pushkin sent an insulting letter to old Heeckeren, accusing him of being the author of the “certificate” of November 4 and the “pander” of his “bastard.” A duel with d’Anthes took place on January 27, 1837. D’Anthes fired first, and Pushkin was mortally wounded; after he fell, he summoned the strength to fire his shot and to wound, slightly, his adversary. Pushkin died two days later, on January 29.

As Pushkin lay dying, and after his death, except for a few friends, court society sympathized with d’Anthes, but thousands of people of all other social levels came to Pushkin’s apartment to express sympathy and to mourn. The government obviously feared a political demonstration. To prevent public display, the funeral was shifted from St. Isaac’s Cathedral to the small Royal Stables Church, with admission by ticket only to members of the court and diplomatic society. And then his body was sent away, in secret and at midnight. He was buried beside his mother at dawn on February 6, 1837 at Svyatye Gory Monastery, near Mikhaylovskoe.