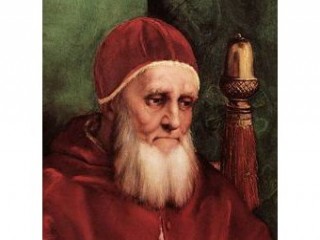

Pope Julius II biography

Date of birth : 1443-12-05

Date of death : 1513-02-21

Birthplace : Albisola, Republic of Genoa

Nationality : Italian

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-08-25

Credited as : Pope, The Fearsome Pope, Basilica

Pope Julius II, who was pope from 1503 to 1513, was a noted Renaissance patron of the arts. A warrior pope, he failed to bring Italy under papal control. His costly concern with the arts and politics alienated northern Europe and helped pave the way for the Reformation.

Giuliano della Rovere, who became Pope Julius II, was born in December 1443 in Albissola near Savona, Italy. He was elevated to the cardinalate in December 1471 by his uncle Pope Sixtus IV. Giuliano rapidly became an influential member of the College of Cardinals and servant to both Sixtus IV and his successor, Innocent VIII. In 1492 Innocent VIII died, and Cardinal della Rovere was considered Innocent's logical successor. However, because of the greater wealth of the Spaniard Cardinal (Rodrigo) Borgia to purchase votes, the College of Cardinals elected Borgia, and he assumed the title Alexander VI.

The Borgias were vassals of Ferdinand of Aragon, and during Alexander's reign Giuliano resented this foreign influence in Italy and also opposed Alexander's nepotism. Because of his opposition to the Pope, Giuliano underwent much hardship. During most of Alexander's pontificate Giuliano felt it safer to absent himself from Rome.

Alexander VI died in August 1503, and his elderly successor, Pius III, died in October. In November Giuliano was elected pope and assumed the title Julius II.

From the start of his pontificate it became clear that Julius intended to make the papacy the dominant political and military force in Italy and to drive all rivals of papal authority out of the peninsula. In 1503 there were three rivals to papal authority. The first was Cesare Borgia, the son of Alexander VI and conqueror of the richest of the Papal States, the Romagna, in northern Italy. The other rivals were Venice and France. France controlled several important cities in northern Italy, among them Florence and Pavia.

In 1504 Julius confiscated the landholdings of Cesare Borgia in Italy and ordered his arrest. In the absence of Cesare Borgia and his military forces in the Romagna, Venice occupied the area, including the cities of Rimini, Faenza, Forli, and Cesena. Julius knew the defeat of this second rival to papal authority would require force of arms. In order to raise the money necessary to equip an army, Julius ordered the Dominicans in Germany to sell indulgences. In 1505 Julius marched out of Rome with a small army.

En route to the Romagna, Julius captured the cities of Perugia and Bologna in 1506. Julius then led his troops into Cesena and Forli, which had been evacuated by the Venetians in the face of a threat by Julius to lay an interdict upon Venice. However, Venice adamantly refused to evacuate Faenza and Rimini. Meanwhile, in 1507 the Genoese revolted against their overlord, Piero Soderini, ruler of Florence and a political puppet of France. The French believed Julius had engineered the revolt in order to force their withdrawal from Italy, and the French king, Louis XII, dispatched an army to smash the insurrection. This threat forced Julius to abandon his campaign against Venice and return to Rome.

The enmity between Louis XII and Julius increased when the Holy Roman emperor Maximilian I announced his intention of journeying to Rome in order to be crowned by the Pope. Louis XII feared that Julius had invited the Germans into Italy to participate in another effort to drive France from the peninsula. Since the Venetians also felt threatened by what they believed to be a papal-German alliance, France and Venice formed an alliance. In 1508 war broke out between the Germans and the Franco-Venetian alliance, and before the end of the year the alliance defeated the Germans.

Because of its assistance in this war, France expected to receive territory in northern Italy from Venice, but Venice relinquished no lands. Louis XII also realized Julius had not invited Maximilian into Italy. France, therefore, abandoned its alliance with the Venetians.

Julius took advantage of the Venetian isolation and created the military League of Cambrai to drive Venice from Faenza and Rimini. France and a number of independent city-states in northern Italy joined the league. Maximilian joined in order to revenge his defeat and win back territory in northern Italy which he had lost to the Venetians. Spain, which controlled the kingdom of Naples, also participated in order to drive the Venetians from Adriatic seaports which they held in that kingdom. In 1509 Julius placed an interdict on Venice, and the League of Cambrai declared war on the city-state.

Venice suffered a number of disastrous defeats on land and sea. The French insisted upon the total destruction of Venice as a power in Italy. But this would have upset the balance of power in northern Italy and would have removed a major obstacle to French domination of that area. Therefore, in 1510 Julius negotiated a separate peace with Venice. By the terms of the settlement, Venice surrendered the Romagna to the Pope, the Apulian seaports to the Spanish, and most of its possessions in northern Italy to the other members of the League of Cambrai. Because of this separate peace the members of the League of Cambrai ended hostilities against Venice. Thus, Julius saved the republic of Venice from annihilation.

Julius now had to deal with the final threat to papal supremacy in Italy, the French. In August 1510 Louis XII called all French prelates to a synod at Orleans. Here, Louis declared that papal authority extended only over spiritual matters. He proclaimed his right as a prince and protector of the Church on earth to call a council in order to punish a worldly pope such as Julius and reform the Church. Louis thus hoped to frighten Julius into abandoning his plans to drive France from Italy.

In 1511 Louis XII issued the call for a Church council. By May a small number of cardinals had gathered at Pisa. Louis promised these cardinals rich rewards for their participation. Support for the council also came from Germany, where the 16th-century voices of reform assailed the worldliness of a papacy which seemed more concerned with Italian politics than with religion. The Germans resented the financial burdens placed upon them by the Pope in order to pay for his wars in Italy.

In the face of disaster Julius acted with characteristic audacity. He issued the call for Western Christendom to gather in ecumenical council at the Lateran Basilica in Rome. This bold action won for Julius the religious and political support of the Spanish and the English. These powers, along with the Swiss and the Venetians, in 1511 joined Julius in the Holy League. In fear of this new military alliance, Louis XII withdrew his support of the schismatic Council of Pisa, and at the beginning of 1512 the council ended in failure.

In June 1512 the Holy League attacked the French in northern Italy. The Swiss captured the French-controlled city of Pavia, and the Spanish captured Florence. By the end of the summer the league drove the French out of Italy.

The defeat of the French was a Pyrrhic victory for Julius, for now the Spanish were in control of much of northern Italy. Julius began preparing new alliances to drive them from Italy. But the energy expended through long years of warfare and in manipulating the complicated balance of power in Italy physically and mentally overtaxed Julius. On February 21, 1513, Julius II died.

During his pontificate Julius hired the costly services of the greatest artists of the Renaissance to embellish the papal apartments. Above the protests of most of Western Christendom he ordered the demolition of the ancient and crumbling Basilica of St. Peter. He hired the services of the architect Donato Bramante, who designed and began the construction of the present Basilica. Julius hired Michelangelo to design and execute a tomb for the Pontiff and to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. All of this and his wars and political escapades in Italy, Julius financed in large part by the sale of ecclesiastical offices and indulgences in northern Europe.