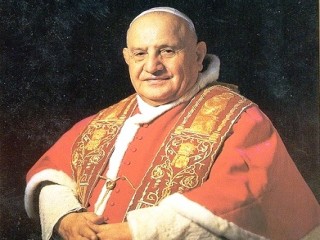

Pope John XXIII biography

Date of birth : 1881-11-25

Date of death : 1963-06-03

Birthplace : Sotto il Monte, Bergamo, Italy

Nationality : Italian

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-08-09

Credited as : Pope, Vatican Council,

Pope John XXIII was pope from 1958 to 1963. He convoked the Second Vatican Council, thus launching a renewal in the Roman Catholic Church and inaugurating a new era in its history.

The future pope was born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli at Sotto il Monte (Bergamo), Italy, on Nov. 25, 1881, the third child and eldest son in the family of 13 born to Giovanni Battista and Marianna Giulia (Mazzola) Roncalli. The boy's forebears for several generations had been tenant farmers on an estate, and even when he reigned in the Vatican, his brothers were still engaged in eking a plain livelihood out of the hard and unfriendly Bergamo soil.

The simple piety of Italian peasants was the most important element in the life of the Roncallis and led Angelo, following elementary education, to enter the diocesan minor seminary in Bergamo at the age of 12. His studies for the priesthood continued at the Seminario Romano ("Apollinare") in Rome but were interrupted for a year of volunteer service in the Italian army. He was ordained on Aug. 10, 1904, and shortly thereafter was named secretary to the new bishop of Bergamo, Count Giacomo Radini-Tedeschi.

The latter was an extremely vigorous, farseeing prelate deeply concerned about social reforms, and the young Father Roncalli, during the 9 years that he served him, gained invaluable knowledge and experience in the problems of the working class and the poor. Simultaneously he taught patrology and Church history in the Bergamo seminary. Radini-Tedeschi died in August 1914, just as World War I was breaking out, and since his successor was a man of quite different temperament, Roncalli decided to enlist. He served first in the medical corps and later as a lieutenant in the chaplains' corps.

At the war's end Pope Benedict XV, who as a close friend of Radini-Tedeschi had come to know Roncalli, asked him to handle the arrangements for the 1920 Eucharistic Congress in Bergamo; and it was undoubtedly as a result of the way in which he organized this event that a year later he was made director of the Italian Society for the Propagation of the Faith. This was a delicate assignment since it involved not only modernizing the society but detaching responsibility from numerous regional directors and centralizing administration in Rome. He remained in this post for 4 years, until Pius XI appointed him apostolic visitor to Bulgaria. For this it was desirable that he hold a higher ecclesiastical rank, and he was named titular archbishop of Areopolis and consecrated to the episcopate on March 19, 1925.

This was the beginning of a diplomatic career which was to last for almost 30 years and take Roncalli to many European countries. In Bulgaria, since the state religion was Orthodox, his presence was resented by both government and Orthodox Church authorities. Yet he managed to provide spiritual leadership for the 40,000 Latin-rite and 4,000 Eastern-rite Catholics scattered thinly among the population. In 1934 he was named apostolic delegate to Turkey and Greece, where his position was, if possible, even more precarious. The Turkish government of Kemal Atatük was aggressively antireligious, but Roncalli, by personal charm and diplomatic finesse, managed to be on friendly terms with authorities.

During World War II, Istanbul, as the capital of a neutral power, was a hotbed of intrigue and espionage, and Roncalli provided the Holy See with much valuable information gleaned from personal contacts as well as official connections. He was instrumental in helping many Jewish refugees fleeing from central Europe through his friendship with the German ambassador to Turkey, Franz von Papen. In Greece his efforts were less successful, since he was of the same nationality as the occupying troops; but here, too, he worked hard to provide food, shelter, and safety for many thousands of refugees.

In 1944, following the liberation of France, Pius XII named Roncalli papal nuncio to that country. The position was even more difficult and challenging than his earlier ones, since the nation was split by many bitter political and religious divisions resulting from the period of occupation and resistance. Roncalli labored patiently and skillfully to repair them, maintaining cordial relations with the governments that came and went in rapid succession. Among other things he was instrumental in securing government subsidies for pupils in private schools, and he viewed with sympathy the "workerpriest" movement.

On Jan. 12, 1953, Pius XII elevated Roncalli to the Sacred College of Cardinals, and on Jan. 15, in accordance with long-standing tradition, he received his red hat from President Vincent Auriol in the Ãlysée Palace. On that same day he was named patriarch of Venice and took possession of his new see on March 15. This enabled him to be at last what he had always wanted to be, a "shepherd of souls" and during his years in Venice he was a vigorous and much-loved prelate, visiting all the parishes in his diocese and creating 30 new ones. He erected a new minor seminary, initiated various forms of Catholic Action, and showed special concern for the poor.

Pius XII died on Oct. 9, 1958, and on Oct. 25 Roncalli entered the conclave which was to choose a successor. He was himself elected 3 days later and took the name John XXIII, the first pope to bear this name since 1334.

John XXIII was 76 years old when he came to the papal throne, and his age—plus the fact that he was not widely known—led many persons to assume that he would simply be a transitional or "caretaker" pope. Inevitably his reign was brief, but in terms of its significance and its effects upon religious and world history it was perhaps the most important pontificate since the Middle Ages.

Much of this significance stemmed, naturally, from the train of events which he set in motion during the 5 years of his reign, but much of it also lay in his unique personality. Previous popes had usually been remote and austere figures; from the very outset John endeared himself to the whole world by his warmth, humor, and easy approachability. He had an impatience with empty traditionalism and often astonished his aides by the forthright way in which he cut through meaningless formalities.

For example, it had always been customary for the pope to dine alone; within a week after his election John announced that he could find nothing in either Revelation or canon law that required such a thing and that henceforth, when the mood was upon him, he would have guests in to dinner. He became the first pope in 200 years to attend the theater by having T. S. Eliot's Murder in the Cathedral performed before him in the papal apartments. He literally horrified Vatican officials and the Italian government by having his chauffeur drive him unannounced and un-escorted through the streets of Rome. He visited— sometimes at very short notice-hospitals, nursing homes, and even prisons. (It is said that when he declared his intention of paying a Christmas visit to Rome's Regina Coeli prison, one of his aides protested that there was simply no protocol for such a thing, and the Pope replied," Well, then, make some!")

The conclave that had elected Pope John had been reduced to 52 cardinals, of whom 12 were more than 80 years old; one of his first acts was a consistory (Dec. 15, 1958) at which he elevated 23 prelates to the Sacred College, including many younger and more vigorous men. By so doing he broke the rule, established in 1586 by Sixtus V, limiting the number of cardinals to 70 and also gave the College much wider geographical representation than it had known until that time. In three subsequent consistories he expanded the membership to 87, its highest figure to that date.

But the most momentous act of his pontificate was, of course, his decision to call an ecumenical council of the Universal Church, the first since 1870 and only the twenty-first in the Church's 2,000-year history.

Following the definition of papal infallibility at Vatican I, it had been assumed in many quarters that there would never again be need for a council. Pope John's motive in calling one was, as he said, to bring about a renewal—a "new Pentecost"—in the life of the Church, to adapt its organization and teaching to the needs of the modern world, and to have as its more far-reaching goal the eventual unity of all Christians. The term which he used to describe what he had in mind—and which was to become a kind of keynote for the Council in the years that followed—was aggiornamento, an Italian word literally meaning "bringing up to date."

In addition to the frequent and demanding general audiences, Pope John met with many outstanding world figures. Among those received at the Vatican during his reign were Queen Elizabeth II of England, U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower, Mrs. Jacqueline Kennedy, the Shah of Iran, and—in a move which surprised many—Alexei Adzhubei, son-in-law of Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and editor of the Russian newspaper Izvestia. This last reception appeared part of a gradual relaxation of the hitherto implacable hostility between the Church and communism, at least one practical result of which was the release of the Ukrainian archbishop Josyf Slipyi, who had been imprisoned for years in Siberia by Soviet authorities.

International tensions and the crises generated by "hot" and "cold" wars also greatly preoccupied the Pontiff. In September 1961 he issued an urgent appeal to the heads of the governments involved in the threatening Berlin crisis. He endeavored to mediate between the French government and the revolutionaries in the Algerian crisis of June 1962. He made an especially fervent appeal to President John F. Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962. It was undoubtedly in recognition of his untiring efforts to bring about world peace that the International Balzan Committee awarded him its Peace Prize in 1962.

After 3 1/2 years of intensive preparation, the Second Vatican Council convened in St. Peter's on Oct. 11, 1962. In his memorable opening address Pope John declared that its purpose, unlike that of many previous councils, was not to condemn error but rather to study more deeply the truths of Catholic teaching and to offer those truths to the modern world in a language that would be meaningful and relevant to it. "The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith," he said," is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another." And he emphatically disagreed with the "prophets of gloom" who saw the modern world as heading toward disaster. During the Council's first session, which lasted from Oct. 11 to Dec. 8, 1962, Pope John took care that its members should work in an atmosphere of complete freedom.

But Pope John was not destined to see the end of the Council which he had started. Even while the first session was in progress, it became evident that he was not in good health, but only those closest to him were aware—as he himself was—that he was suffering from a gastric cancer which, because of his great age, was considered by the doctors to be inoperable. During the following months his condition gradually worsened, and much of the time he was in great pain. He appeared at his window overlooking St. Peter's Square for the last time on May 23, 1963. Shortly thereafter he was confined to bed, and during the next few days he sank rapidly. At one point he did rally enough to talk to members of his family and to tell his physician, "My bags are packed and I am ready, very ready, to go." He passed quietly away on June 3, 1963, mourned as perhaps no other figure in world history had been and was interred in the crypt of St. Peter's 4 days later. On Nov. 18, 1965, his successor, Paul VI, announced that beatification procedures had been initiated for him as well as for Pius XII.

One of the most notable features of Pope John's reign was the great advance in ecumenical relations between the Catholic Church and other religious bodies. He envisioned Christian unity as one of the ultimate goals of the Council, and one of the bodies that he set up for the Council's work was the Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity, under the chairmanship of the Jesuit cardinal Augustinus Bea. This body was subsequently raised to the dignity of a full commission. Large numbers of Protestant and Orthodox clergy were invited as observers to the Council. Pope John met with them on a number of occasions and—as with everyone else—completely won them over by his warmth, simplicity, and openness of manner. In December 1960 he received at the Vatican the archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Francis Fisher—the first meeting ever held between a Roman pope and an Anglican primate. A year later, in November 1961, history was made again when for the first time the Catholic Church was represented at a meeting of the World Council of Churches: Bea's office sent five official priestobservers to the Third General Assembly in New Delhi.

Pope John's ecumenical efforts, however, were not confined to Protestantism. Catholic theologians met with members of the Orthodox Church for discussions at Rhodes in August 1959, and the Holy See sent envoys to Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople in June 1961. And he showed equal consideration to those of the Jewish faith: one of his acts, seemingly trivial but actually bearing immense significance, was his directive to remove from the centuries-old Good Friday liturgy its reference to the "perfidious Jews."

Pope John issued eight encyclicals during his reign, and at lest two deserve to be ranked with the most important documents of Church history. These are Mater et Magistra (Mother and Teacher), issued May 15, 1961, and Pacem in terris (Peace on Earth), dated April 11, 1963.

Mater et Magistra restated the social teaching of the Church as set forth in Leo XIII's Rerum novarum and Pius XI's Quadragesimo anno but greatly amplified it in the light of later developments and problems. Among other things, the Pontiff pointed out the right that all classes have to benefit from technological advances and stressed the obligation of large and wealthy nations to assist underdeveloped ones. It was perhaps natural that the son of a poor farming family should lay special emphasis on the necessity for improved agricultural methods in still backward countries.

Pacem in terris was unique among papal encyclicals in being the first one ever addressed not just to Catholics but " to all men of good will." Pope John enumerated the rights of the human person—to life, to respect, to freedom, to an education, to be informed, and numerous others—and dwelt at length on the obligations of the citizen to the state and of states to their citizens and to each other. He pleaded for the banning of nuclear weapons and an end to the arms race. Pointing out that the problems of modern times could not be solved unilaterally, he expressed hope that the United Nations would prove an ever more effective instrument for mutual cooperation among nations and for the preservation of world peace.

John XXIII, the son of simple Italian peasants, never lost either the simplicity or the humility that were part of his origins. It was precisely these qualities, indeed, that made him so unique in his times. Unlike his predecessor and successor, he was not a scholar or a theologian (though he was a highly cultured man with a profound knowledge of history, a love for literature, art, and music, and a fluency in many languages); but he had an intuitive understanding of people and problems that enabled him to deal with them in way that scholars perhaps could not have done. It is no exaggeration but a literal truth to say that he loved everyone, and that this in turn caused everyone to love him.

In an age largely given over to secularism, he not only increased the prestige of the papacy but also restored the importance and relevance of religion to a degree that few would have thought possible. By concentrating on what unites men rather than on what divides them, he took the first steps toward the eventual unity of all Christians. When he was elected, many thought that his pontificate would be a transitional one, and in a sense this was true. The transition, however, was not merely from one pope to another, but also and especially from an old to a new era of religious history.