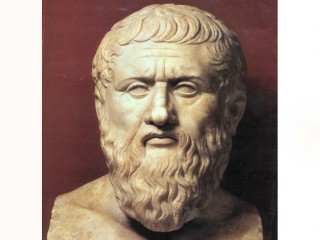

Plato biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Athens, Greece

Nationality : Greek

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2010-05-25

Credited as : Philosopher and mathematician, Apology, Socrates and Aristotle

Plato's sophistication as a writer is evident in his Socratic dialogues; thirty-six dialogues and thirteen letters have been ascribed to him. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts.

Plato's dialogues have been used to teach a range of subjects, including philosophy, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, and other subjects about which he wrote.

Known to have one of the greatest influences on modern Western thought, and to have taught his ways to Aristotle in the Academy, Plato is considered one of the greatest minds and logical rationalists in world history. While his works often border mysticism, his continual pursuit of ethical answers based on logical processes still influences law, politics, education, ethics, philosophy, and psychology even today.

Not much is known about the days of young Plato. He was of some higher social class, hence his elitist education and his ability to travel to Sicily and even as far as Egypt. Being brought up in a noble family meant that he would have access to the best libraries and teachers available in his day. While he always preferred to stay in Athens, he knew a lot about the outside world, mainly through reading and intimate discussions with others. Even as a young boy, Plato wrote poetry, plays, and his association with Socrates gained him national recognition by others of young nobility in Athens.

In Plato’s work, the Apology, show that he was active in government following the Phoenician conflicts. But, from this moment on, Plato never took an active role in the politics of his day and instead resorted to spending time pursuit of his own education. Plato traveled to Athens and remained with Dionysius in Sicily for some time. When Plato returned to Athens, he was dropped off on the nearby island of Aegina and had to make his own way back to Athens.

Upon his return, Plato opened up his own academy and founded it as a gymnasium, similar to what Aristotle opened several years later. The Academy remained in operation until the arrival of Christian emperors. While here, Plato began writing his Dialogues, which is how he is most remembered today. His dialogues discuss certain humane virtues personified and laid the foundation of all his and his followers’ future philosophies. In the dialogues, Socrates discusses and debates each virtue, showing what is wrong with each one according to a new model of thinking.

Socrates also appears in the Symposium and in the Republic, where a utopia is founded based upon the harmony of the soul, which is made up of three parts: the rational, less rational, and the impulsive. Through these writings, one learns how wisdom, courage, and justice greatly affect a society that is attempting perfection.

Works

Thirty-six dialogues and thirteen letters have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts.

The usual system for making unique references to sections of the text by Plato derives from a 16th century edition of Plato's works by Henricus Stephanus. An overview of Plato's writings according to this system can be found in the Stephanus pagination article.

One tradition regarding the arrangement of Plato's texts is according to tetralogies. This scheme is ascribed by Diogenes Laertius to an ancient scholar and court astrologer to Tiberius named Thrasyllus.

In the list below, works by Plato are marked (1) if there is no consensus among scholars as to whether Plato is the author, and (2) if scholars generally agree that Plato is not the author of the work. Unmarked works are assumed to have been written by Plato.

* I. Euthyphro, (The) Apology (of Socrates), Crito, Phaedo

* II. Cratylus, Theaetetus, Sophist, Statesman

* III. Parmenides, Philebus, (The) Symposium, Phaedrus

* IV. First Alcibiades (1), Second Alcibiades (2), Hipparchus (2), (The) (Rival) Lovers (2)

* V. Theages (2), Charmides, Laches, Lysis

* VI. Euthydemus, Protagoras, Gorgias, Meno

* VII. (Greater) Hippias (major) (1), (Lesser) Hippias (minor), Ion, Menexenus

* VIII. Clitophon (1), (The) Republic, Timaeus, Critias

* IX. Minos (2), (The) Laws, Epinomis (2), Epistles (1).

The remaining works were transmitted under Plato's name, most of them already considered spurious in antiquity, and so were not included by Thrasyllus in his tetralogical arrangement. These works are labelled as Notheuomenoi ("spurious") or Apocrypha.

* Axiochus (2), Definitions (2), Demodocus (2), Epigrams, Eryxias (2), Halcyon (2), On Justice (2), On Virtue (2), Sisyphus (2).

Plato's Dialogues

The exact order in which Plato's dialogues were written is not known, nor is the extent to which some might have been later revised and rewritten.

Lewis Campbell was the first to make exhaustive use of stylometry to prove objectively that the Critias, Timaeus, Laws, Philebus, Sophist, and Statesman were all clustered together as a group, while the Parmenides, Phaedrus, Republic, and Theaetetus belong to a separate group, which must be earlier (given Aristotle's statement in his Politics that the Laws was written after the Republic; cf. Diogenes Laertius Lives 3.37). What is remarkable about Campbell's conclusions is that, in spite of all the stylometric studies that have been conducted since his time, perhaps the only chronological fact about Plato's works that can now be said to be proven by stylometry is the fact that Critias, Timaeus, Laws, Philebus, Sophist, and Statesman are the latest of Plato's dialogues, the others earlier.

Increasingly in the most recent Plato scholarship, writers are skeptical of the notion that the order of Plato's writings can be established with any precision, though Plato's works are still often characterized as falling at least roughly into three groups. The following represents one relatively common such division. It should, however, be kept in mind that many of the positions in the ordering are still highly disputed, and also that the very notion that Plato's dialogues can or should be "ordered" is by no means universally accepted.

* Apology - in Greek, Απολογία

* Charmides - in Greek, Χαρμίδης

* Crito - in Greek, Κρίτων

* Euthyphro

* Ion

* Laches

* Lesser Hippias

* Lysis

* Menexenus

* Protagoras is often considered one of the last of these "earlier" dialogues.

The following are often considered "transitional" or "pre-middle" dialogues:

* Euthydemus

* Gorgias

* Meno

* Cratylus

* Parmenides

* Phaedo

* Phaedrus

* Republic

* Symposium

* Theaetetus

* Critias

* Laws

* Philebus

* Sophist

* Statesman

* Timaeus