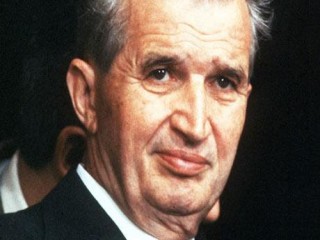

Nicolae Ceausescu biography

Date of birth : 1918-01-26

Date of death : 1989-12-25

Birthplace : Scornicești, Olt County, Romania

Nationality : Romanian

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-08-30

Credited as : Politician, President of Romania, Communist Party

0 votes so far

His rule was marked in the first decade by an open policy towards Western Europe, and the United States, which deviated from that of the other Warsaw Pact states during the Cold War. He continued a trend first established by his predecessor, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, who had tactfully coaxed the Soviet Union into withdrawing its troops from Romania in 1958.

Ceaușescu's second decade was characterized by an increasingly erratic personality cult, nationalism and a deterioration in foreign relations with the Western powers as well as the Soviet Union. Ceaușescu's government was overthrown in the December 1989 revolution, and he and his wife were executed following a televised and hastily organised two-hour court session.

Born in the village of Scornicești, Olt County, Ceaușescu moved to Bucharest at the age of 11 to work in the factories. He was the son of a peasant (see Ceaușescu family for descriptions of his parents and siblings.) He joined the then-illegal Communist Party of Romania in early 1932 and was first arrested, in 1933, for street fighting during a strike. He was arrested again, in 1934, first for collecting signatures on a petition protesting the trial of railway workers and twice more for other similar activities. These arrests earned him the description "dangerous communist agitator" and "active distributor of communist and anti-fascist propaganda" on his police record. He then went underground, but was captured and imprisoned in 1936 for two years at Doftana Prison for anti-fascist activities.

While out of jail in 1940, he met Elena Petrescu, whom he married in 1946 and who would play an increasing role in his political life over the years. He was arrested and imprisoned again in 1940. In 1943, he was transferred to Târgu Jiu internment camp where he shared a cell with Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, becoming his protégé. After World War II, when Romania was beginning to fall under Soviet influence, he served as secretary of the Union of Communist Youth (1944-1945).

After the Communists seized power in Romania in 1947, he headed the Ministry of Agriculture, then served as Deputy Minister of the Armed Forces under Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. In 1952, Gheorghiu-Dej brought him onto the Central Committee months after the party's "Muscovite faction" led by Ana Pauker had been purged. In 1954, he became a full member of the Politburo and eventually rose to occupy the second-highest position in the party hierarchy.

Three days after the death of Gheorghiu-Dej in March 1965, Ceaușescu became first secretary of the Romanian Workers' Party. One of his first acts was to change the name of the party to The Romanian Communist Party, and declare the country the Socialist Republic of Romania rather than a People's Republic. In 1967, he consolidated his power by becoming president of the State Council.

Initially, Ceaușescu became a popular figure in Romania and also in the Western World, due to his independent foreign policy, challenging the authority of the Soviet Union. In the 1960s, he ended Romania's active participation in the Warsaw Pact (though Romania formally remained a member); he refused to take part in the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces, and actively and openly condemned that action. Although the Soviet Union largely tolerated Ceaușescu's recalcitrance, his seeming independence from Moscow earned Romania maverick status within the Eastern Bloc.

During the following years Ceaușescu pursued an open policy towards the United States and Western Europe. Romania was the first Communist country to recognize West Germany, the first to join the International Monetary Fund, and the first to receive a US President, Richard Nixon. In 1971 Romania became a member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Romania and Yugoslavia were also the only East European countries that entered into trade agreements with the European Economic Community before the fall of the Communist bloc.

A series of official visits to Western countries (including the US, France, United Kingdom, Spain) helped Ceaușescu to present himself as a reforming Communist, pursuing an independent foreign policy within the Soviet Bloc. Also he became eager to be seen as an enlightened international statesman, able to mediate in international conflicts and to gain international respect for Romania. Ceaușescu negotiated in international affairs, such as the opening of US relations with China in 1969 and the visit of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat to Israel in 1977. Also Romania was the only country in the world to maintain normal diplomatic relations with both Israel and the PLO.

In 1966, the Ceaușescu regime, in an attempt to boost the country's population, made abortion illegal, and introduced other policies to reverse the very low birth rate and fertility rate. Abortion was permitted only in cases where the woman in question was over forty-two, or already the mother of four (later five) children. Mothers of at least five children would be entitled to significant benefits, while mothers of at least ten children were declared heroine mothers by the Romanian state. However, few women ever sought this status; instead, the average Romanian family during the time had two to three children. Furthermore, a considerable number of women either died or were maimed during clandestine abortions.

The government also targeted rising divorce rates and made divorce much more difficult - it was decreed that a marriage could be dissolved only in exceptional cases. By the late 1960s, the population began to swell. In turn, a new problem was created by child abandonment, which swelled the orphanage population. The transfusions of untested blood, led to Romania accounting for many of Europe's pediatric HIV/AIDS cases at the turn of the century despite having a population that only makes up around 3% of Europe.

Ceaușescu visited the People's Republic of China, North Korea, and North Vietnam in 1971 and was inspired by the hardline model he found there. He took great interest in the idea of total national transformation as embodied in the programs of the Korean Workers' Party and China's Cultural Revolution. Shortly after returning home, he began to emulate North Korea's system, influenced by the Juche philosophy of North Korean President Kim Il Sung. North Korean books on Juche were translated into Romanian and widely distributed in the country. On 6 July 1971, he delivered a speech before the Executive Committee of the PCR.

This quasi-Maoist speech, which came to be known as the July Theses, contained seventeen proposals. Among these were: continuous growth in the "leading role" of the Party; improvement of Party education and of mass political action; youth participation on large construction projects as part of their "patriotic work"; an intensification of political-ideological education in schools and universities, as well as in children's, youth and student organizations; and an expansion of political propaganda, orienting radio and television shows to this end, as well as publishing houses, theatres and cinemas, opera, ballet, artists' unions, promoting a "militant, revolutionary" character in artistic productions. The liberalization of 1965 was condemned and an index of banned books and authors was re-established.

The Theses heralded the beginning of a "mini cultural revolution" in Romania, launching a Neo-Stalinist offensive against cultural autonomy, reaffirming an ideological basis for literature that, in theory, the Party had hardly abandoned. Although presented in terms of "Socialist Humanism", the Theses in fact marked a return to the strict guidelines of Socialist Realism, and attacks on non-compliant intellectuals. Strict ideological conformity in the humanities and social sciences was demanded. Competence and aesthetics were to be replaced by ideology; professionals were to be replaced by agitators; and culture was once again to become an instrument for political-ideological propaganda.

In 1974, Ceaușescu became President of the Socialist Republic of Romania, further consolidating his power. He continued to follow an independent policy in foreign relationsfor example, in 1984, Romania was one of only three communist states (the others being the People's Republic of China, and Yugoslavia) to take part in the American-organized 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Also, the Socialist Republic of Romania was the first of the Eastern bloc to have official relations with the Western bloc and European Community: an agreement including Romania in the Community's Generalised System of Preferences was signed in 1974 and an Agreement on Industrial Products was signed in 1980. On 4 April 1975, Ceaușescu visited Japan and met with Hirohito.

In 1978, Ion Mihai Pacepa, a senior member of the Romanian political police (Securitate), defected to the United States. A 2-star general, he was the highest ranking defector from the Eastern Bloc in the history of the Cold War. His defection was a powerful blow against the regime, forcing Ceaușescu to overhaul the architecture of the Securitate. Pacepa's 1986 book, Red Horizons: Chronicles of a Communist Spy Chief claims to expose details of Ceaușescu's regime, such as massive spying on American industry and elaborate efforts to rally Western political support.

After Pacepa's defection, the country became more isolated and economic growth faltered. Ceaușescu's intelligence agency became subject to heavy infiltration by foreign intelligence agencies and he started to lose control of the country. He tried several reorganizations in a bid to get rid of old collaborators of Pacepa, but to no avail.

Ceaușescu's political independence from the Soviet Union and his protest against the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 drew the interest of Western powers, who briefly believed he was an anti-Soviet maverick and hoped to create a schism in the Warsaw Pact by funding him. Ceaușescu did not realize that the funding was not always favorable. Ceaușescu was able to borrow heavily (more than $13 billion) from the West to finance economic development programs, but these loans ultimately devastated the country's finances. In an attempt to correct this, Ceaușescu decided to repay Romania's foreign debts. He organized a referendum and managed to change the constitution, adding a clause that barred Romania from taking foreign loans in the future. The referendum yielded a nearly unanimous "yes" vote.

In the 1980s, Ceaușescu ordered the export of much of the country's agricultural and industrial production in order to repay its debts. The resulting domestic shortages made the everyday life of Romanians a fight for survival as food rationing was introduced and heating, gas and electricity black-outs became the rule. During the 1980s, there was a steady decrease in the living standard, especially the availability and quality of food and general goods in stores. The official explanation was that the country was paying its debts and people accepted the suffering, believing it to be for a short time only and for the ultimate good.

The debt was fully paid in summer 1989, shortly before Ceaușescu was overthrown, but heavy exports continued until the revolution in December.

By early 1989, Ceaușescu was showing signs of complete denial of reality. While the country was going through extremely difficult times with long bread queues in front of empty food shops, he was often shown on state TV entering stores filled with food supplies, visiting large food and arts festivals, while praising the "high living standard" achieved under his rule.

Special contingents of food deliveries would fill stores before his visits, and well-fed cows would even be transported across the country in anticipation of his visits to farms. In at least one emergency, he inspected (and approved) a display of Hungarian produce, which apart from some corn and several melons, was largely constructed of painted plastic and/or polystyrene. Meanwhile, staples such as flour, eggs, butter and milk were difficult to find and most people started to depend on small gardens grown either in small city alleys or out in the country. In late 1989, daily TV broadcasts showed lists of CAPs (kolkhozes, collective farms) with alleged record harvests, in blatant contradiction to the shortages experienced by the average Romanian at the time.

Some people, believing that Ceaușescu was not aware of what was going on in the country outside of Bucharest, attempted to hand him petitions and complaint letters during his many visits around the country. However, each time he got a letter, he would immediately pass it on to members of his security. Whether or not Ceaușescu ever read any of these letters will probably remain unknown. It was common knowledge that people attempting to hand letters directly to Ceaușescu risked adverse consequences, courtesy of the Securitate. People were strongly discouraged from addressing him directly and there was a general sense that morale in Romania had reached an overall low.

In November 1989, the XIVth Congress of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) saw Ceaușescu, then aged 71, re-elected for another five years as leader of the PCR. But the following month, Ceaușescu's regime collapsed after a series of violent events in Timișoara and Bucharest in December 1989.

Timișoara

Demonstrations in the city of Timișoara were triggered by the government-sponsored attempt to evict Laszlo Tokes, an ethnic Hungarian pastor, accused by the government of inciting ethnic hatred. Members of his ethnic Hungarian congregation surrounded his apartment in a show of support.

Romanian students spontaneously joined the demonstration, which soon lost nearly all connection to its initial cause and became a more general anti-government demonstration. Regular military forces, police and Securitate fired on demonstrators on 17 December 1989, killing and wounding many. On 18 December 1989, Ceaușescu departed for a state visit to Iran, leaving the duty of crushing the Timișoara revolt to his subordinates and his wife. Upon his return to Romania on the evening of 20 December, the situation became even more tense, and he gave a televised speech from the TV studio inside Central Committee Building (CC Building), in which he spoke about the events at Timișoara in terms of an "interference of foreign forces in Romania's internal affairs" and an "external aggression on Romania's sovereignty".

The country, which had little or no information of the Timișoara events from the national media, learned about the Timișoara revolt from western radio stations such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, and by word of mouth. On the next day, 21 December, a mass meeting was staged. Official media presented it as a "spontaneous movement of support for Ceaușescu", emulating the 1968 meeting in which Ceaușescu had spoken against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces.

Overthrow

The mass meeting of 21 December, held in what is now Revolution Square, degenerated into chaos. The image of Ceaușescu's uncomprehending expression as the crowd began to boo and heckle him remains one of the defining moments of the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe. The stunned couple (the dictator and his wife), failing to control the crowds, finally took cover inside the building, where they remained until the next day. The rest of the day saw an open revolt of the Bucharest population, which had assembled in University Square and confronted the police and army at barricades. The unarmed rioters, however, were no match for the military apparatus concentrated in Bucharest, which cleared the streets by midnight and arrested hundreds of people in the process. Nevertheless, these seminal events are regarded to this day as the de facto revolution.

Although the television broadcasts of the "support meeting" and subsequent events had been interrupted, Ceaușescu's reaction to the events had already been imprinted on the country's collective memory. By the morning of 22 December, the rebellion had already spread to all major cities across the country. The suspicious death of Vasile Milea, the defense minister, was announced by the media. Immediately thereafter, Ceaușescu presided over the CPEx (Political Executive Committee) meeting and assumed the leadership of the army. He made a desperate attempt to address the crowd gathered in front of the Central Committee building. This was rejected by the rioters who forced open the doors of the building, by now left unprotected, obliging the Ceaușescus to flee by helicopter.

During the course of the revolution, the western press published estimates of the number of people killed by the Securitate in attempting to support Ceaușescu and quash the rebellion. The count increased rapidly until an estimated 64,000 fatalities were widely reported across front pages. The Hungarian military attaché expressed doubt regarding these figures, pointing out the unfeasible logistics of killing such a large number of people in such a short period of time. After Ceaușescu's death, hospitals across the country reported an actual death toll of less than one thousand, and probably much lower than that.

Ceaușescu and his wife Elena fled the capital with Emil Bobu and Manea Mănescu and headed, by helicopter, for Ceaușescu's Snagov residence, from where they fled again, this time for Târgoviște. Near Târgoviște they abandoned the helicopter, having been ordered to land by the army, which by that time had restricted flying in Romania's air space. The Ceaușescus were held by the police while the policemen listened to the radio. They were eventually turned over to the army. On Christmas Day, 25 December, the two were tried in a brief show-trial and sentenced to death by a military court on charges ranging from illegal gathering of wealth to genocide, and were executed in Târgoviște. The video of the trial shows that, after sentencing, they had their hands tied behind their backs and were led outside the building to be executed.

The Ceaușescus were executed by a firing squad consisting of elite paratroop regiment soldiers: Captain Ionel Boeru, Sergant-Major Georghin Octavian and Dorin-Marian Cirlan, while reportedly hundreds of others also volunteered. The firing squad began shooting as soon as they were in position against a wall. The firing happened too soon for the film crew covering the events to record it. After the shooting, the bodies were covered with canvas. The hasty show trial and the images of the dead Ceaușescus were videotaped and the footage promptly released in numerous western countries. Later that day, it was also shown on Romanian television.

The Ceaușescus were the last people to be executed in Romania before the abolition of capital punishment on 7 January 1990.

Their graves are located in Ghencea cemetery in Bucharest. They are buried on opposite sides of a path. The graves themselves are unassuming, but they tend to be covered in flowers and symbols of the regime. Some allege that the graves do not, in reality, contain their bodies. As of April 2007, their son Valentin has lost an appeal for an investigation into the matter. Upon his death in 1996, the elder son, Nicu, was buried nearby in the same cemetery. According to Jurnalul Național, requests were made by the Ceaușescus' daughter Zoia and by supporters of their political views to move their remains to mausoleums or to purpose-built churches. These have been denied by the government. On 21 July 2010, forensic scientists exhumed the bodies of Nicolae and Elena to perform DNA tests. Later it was determined that they were indeed the remains of Nicolae and Elena.