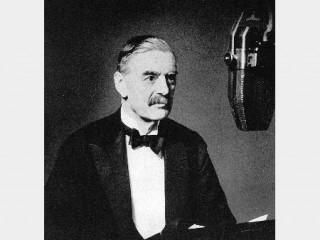

Neville Chamberlain biography

Date of birth : 1869-03-18

Date of death : 1940-11-09

Birthplace : Edgbaston, Birmingham

Nationality : British

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-12-22

Credited as : Politician, prime minister of Great Britain,

The English statesman Arthur Neville Chamberlain was prime minister of Great Britain in the years preceding World War II. He is associated with the policy of appeasement toward Nazi Germany that culminated in the Munich Agreement of 1938.

Neville Chamberlain was born on March 18, 1869, at Edgbaston, Birmingham, the son of Joseph Chamberlain, colonial secretary from 1895 to 1903, and Florence Kenrick Chamberlain. Neville's home and family were the most influential aspects of his education and upbringing. He went to Rugby and then attended Mason College (later a part of the University of Birmingham) for 2 years to study science and engineering, but he did not distinguish himself in his studies. He then worked briefly and more successfully as an apprentice with an accounting firm.

In 1890 his father sent Neville to the island of Andros in the Bahamas to manage his 20,000-acre sisal plantation. Although the venture failed, the 7 years of comparative social isolation contributed to young Chamberlain's natural reserve and also gave him confidence in his own decisions. After returning to Birmingham, he became a leader in the city's industrial and political life.

In 1911 Chamberlain married Annie Cole. He was elected that year to the city council of Birmingham, and in 1915 he became lord mayor of Birmingham.

Chamberlain's record led Lloyd George, the Liberal prime minister, to appoint him as the first director general of National Service in December 1916. Chamberlain was in charge of voluntary recruitment of labor in war industry, but he found himself without authority or organization to execute his duties. He lost confidence in Lloyd George and soon resigned.

In 1918, at the age of 49, Chamberlain entered national politics and was elected to Parliament. As a Conservative, he supported the coalition but would not accept a post under Lloyd George. When a Conservative administration was formed in 1922 under Bonar Law, he accepted appointment as postmaster general; his administrative talents were at once evident, and within a year he advanced rapidly to paymaster general, then to minister of health, and finally to chancellor of the Exchequer. In 1924, in the administration of Stanley Baldwin, he chose to return to the Ministry of Health for he was convinced that the government would rise or fall on its record of social reform.

Indeed, Chamberlain made his reputation as a "radical Conservative" and energetic legislator during these years. His guiding principle in social legislation was that national resources should be used to help those who help themselves. His achievements included the Rating and Valuation Act of 1925, which assisted both agriculture and industry; the Widow, Orphans and Old Age Pension Act of 1925, which extended the act of 1908; the Local Government Act of 1929, which transferred care of the poor from Poor Law Unions to county agencies; and the construction of 400,000 new houses.

In 1931 Chamberlain joined the National government under Ramsay MacDonald, first as minister of health, then as chancellor of the Exchequer. In 1932, when he secured approval for a general tariff of 10 percent, he was adopting proposals urged by his father in 1903. He was responsible for the significant Unemployment Act of 1934, which reformed the system of administering relief. It was with good reason that Winston Churchill called him "the pack horse" of the administration.

If his career had ended in 1937, Chamberlain might well have been recorded as the Conservative who did most for social reform between the wars. Instead, he succeeded Baldwin as prime minister in May 1937 and had to turn his attention abruptly to foreign affairs. Not that he did so with hesitation; here, as always, he faced his task with confidence. He was determined to avert a war, for which neither England nor France was prepared, through a policy of pacification involving collaboration with Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy. Since he believed the League of Nations had failed, he turned to direct negotiation, seeking by compromise and appeasement to dissipate tensions that might lead to war—an approach already accepted by most Englishmen. However, his efforts with Mussolini led only to the resignation of Anthony Eden, his foreign secretary. And as for Hitler, Chamberlain accepted the Nazi takeover of Austria in March 1938 but attempted through negotiation to avert a similar fate for Czechoslovakia.

Chamberlain and Hitler conferred at Berchtesgaden and Godesberg in September and then met at Munich with Mussolini and Edouard Daladier, the French premier. The Munich Agreement was hailed enthusiastically in Britain, and it gave the nation precious time to rearm. But when the Reich absorbed Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Chamberlain realized that his policy of appeasement had failed. He announced military support for Poland and sought to include Russia in a security system. But on Sept. 1, 1939, German forces moved into Poland, and on September 3 Chamberlain broadcast to the nation that Britain was at war.

As a wartime leader, Chamberlain had no talent. The Germans invaded Scandinavia in April 1940, and the fall of Norway, despite desperate British aid, brought a division in the Commons which Chamberlain survived, though some 100 Conservatives either voted against him or abstained. On May 10 he resigned and was succeeded by Winston Churchill. Chamberlain remained as lord president of the council until illness forced him to retire in October. He died a month later on Nov. 9, 1940. His ashes are interred in Westminster Abbey.