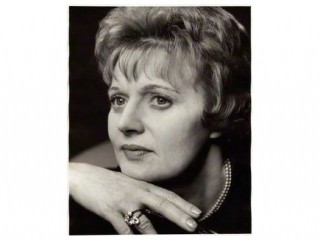

Muriel Spark biography

Date of birth : 1918-02-01

Date of death : 2006-04-13

Birthplace : Edinburgh, Scotland

Nationality : Scottish

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-11-30

Credited as : novelist, literary critic, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

Muriel Sarah Spark wrote biography, literary criticism, poetry, and fiction, including the novel that was considered her masterpiece, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

Born in Edinburgh on February 1, 1918, Muriel Spark worked in the Political Intelligence Department of the British Foreign Office in 1944-1945, was the general secretary of the Poetry Society from 1947 to 1949, and served as the editor of Poetry Review in 1949. She was the founder of the literary magazine Forum and worked as a part-time editor for Peter Owen Ltd.

In the early 1950s Spark published her first poetry collection, The Fanfarlo and Other Verse (1952), and built a solid reputation as a biographer with Child of Light: A Reassessment of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1951); Emily Bronte: Her Life and Work (1953); and John Masefield (1953). She also edited A Collection of Poems by Emily Bronte (1952), My Best Mary: The Letters of Mary Shelley (1954), and, most important, Letters of John Henry Newman (1957).

While working in these areas of nonfiction, Spark was undergoing a crisis of faith and was strongly influenced by the writings of Newman, the 19th-century Anglican clergyman who became a convert to Roman Catholicism and eventually a cardinal in that faith. While she was dealing with her crisis, she received financial and psychological assistance from Graham Greene, also a Roman Catholic convert, and was eventually converted herself, a move that had significant influence on her novels.

Spark published the first of those novels, The Comforters, in 1957 and followed that with Robinson in 1958, the same year she authored her first short-story collection, The Go-Away Bird and Other Stories. In this same period she began writing radio plays, with The Party Through the Wall in 1957, The Interview in 1958, and The Dry River Bed in 1959.

It was in 1959 that Spark had her first major success, Memento Mori, with some critics comparing her to Ivy Compton-Burnett and Evelyn Waugh. She followed this with The Ballad of Peckham Rye in 1960, writing a radio play based on the novel that same year; The Bachelors, also in 1960; and Voices at Play in 1961, likewise turned into a radio play.

In 1961 she also published the novel generally regarded as her masterwork, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, subsequently made into a play, a hit on both sides of the Atlantic in the years 1966-1968; a film in 1969; and a six-part adaptation for television, another transatlantic success, in 1978 and 1979. This was the portrait of a middle-aged teacher at the Marcia Blaine School for Girls in Edinburgh in the 1930s who has gathered around her a coterie of five girls, "The Brodie Set." Jean Brodie was one of those delightful eccentrics, common in English fiction, who walked a tightrope over the abyss of caricature but never tumbled in. She saw her task as "putting old heads on young shoulders" and told her disciples that they were the creme de la creme. In 1939 she was forced to retire on the grounds that she has been teaching fascism, the accusation made by the girl who eventually became a nun and defended herself against charges of betrayal by observing that "It's only possible to betray where loyalty is due." Critic George Stade probably best defined Spark's attitude toward Jean Brodie by pointing out that the novel embodied "the traditional moral wisdom that, if you are not part of something larger than yourself, you are nothing."

In 1962 Spark's sole venture into theater, Doctors of Philosophy, was presented in London and was not a resounding success. She returned to fiction and wrote The Girls of Slender Means (1963); The Mandelbaum Gate (1965); Collected Stories I (1967); The Public Image (1968); The Very Fine Clock (1968), her only work for juveniles; The Driver's Seat (1970); Not To Disturb (1971); and The Hothouse by the East River (1973).

Also in 1973 Sharp published another outstanding novel, The Abbess of Crewe, a work alive with paradox. To win election as abbess, the protagonist, Sister Gertrude, studied Machiavelli; once in charge, she combined an extreme conservatism in religious matters with the installation of electronic devices in the abbey and enlisted the aid of two Jesuit priests in exposing the affair between Sister Felicity and a young Jesuit. Released from the abbey, Sister Gertrude roamed the Third World like a loose cannon, indulging in such projects as mediating a war between a tribe of cannibals and a tribe of vegetarians. The novel was filmed in 1976 under the title Nasty Habits.

Subsequently there came the novels The Takeover (1976); Territorial Rights (1979); Loitering with Intent (1981); A Far Cry from Kensington (1987); The Only Problem (1988); Symposium (1990); Reality and Dreams (1997); and two collections of short stories, Bang-Bang You're Dead and Other Stories (1982) and The Stories of Muriel Spark (1985). In 1992, she published Curriculum Vitae: Autobiography.

Her twentieth novel, Reality and Dreams explored the boundaries and connections between realities and dreams in a story about a dream-driven film director who feels and seeks to be Godlike in his work, a theme which illustrated the aptness of critic Frank Kermode's insight that in Spark's novels portrayed a connection between fiction and the world, and between the creation of the novelist and the creation of God.

Much of the criticism about Spark's work focused on the extent to which her Catholicism influenced her writing; that is, was she a Catholic novelist or a novelist who was incidentally a Catholic? The former view was upheld by American critic Granville Hicks, who termed her "a gloomy Catholic, like Graham Greene and Flannery O'Connor, more concerned with the evil of man than the goodness of God." J.D. Enright, on the other hand, felt that, unlike Paul Claudel or Francois Mauriac or Graham Greene, she had no interest in force-feeding Catholicism to her readers. Religion aside, Duncan Fallowell summed up her fiction in this way: "She is the master, and sometimes mistress, of an attractive, cynical worldliness which is not shallow." And that observation probably best encapsulated British critical opinion, which has been generally kind, if not generous, to her work for four decades.

In 1993, Spark was made Dame Muriel Spark, Order of the British Empire.