Moondog biography

Date of birth : 1916-05-26

Date of death : 1999-09-08

Birthplace : Marysville, Kansas, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-01-03

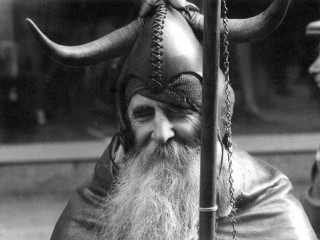

Credited as : composer, inventor of several musical instruments, known as "The Viking of 6th Avenue"

1 votes so far

Moving to New York as a young man, Moondog made a deliberate decision to make his home on the streets there, where he spent approximately twenty of the thirty years he lived in the city. Most days he could be found in his chosen part of town wearing clothes he had created based on his own interpretation of the Norse god Thor. Thanks to his unconventional outfits and lifestyle, he was known for much of his life as "The Viking of 6th Avenue".

Moondog spent much of his extraordinary career panhandling on the corner of Sixth Avenue and 54th Street in New York City, sometimes selling pieces of paper bearing a song or poem he had written. With the fully serious intent of honoring his Nordic ancestors, Moondog wore a Viking outfit, complete with a homemade spear, a long beard, and a helmet with horns. Top musicians in both the classical and jazz fields were well aware of the intricately worked-out and entirely original music that Moondog composed in Braille notation, but he guarded his independence, preferring to live on the streets or in a small upstate New York cabin. Finally, later in his life, he took up residence in Germany in the home of a young geology student who put aside her studies in order to support his creative endeavors. By the time of his death in 1999, many Europeans venerated him as a musical genius.

Moondog was born Louis Thomas Hardin on May 26, 1916, in Marysville, Kansas; in 1947 he named himself Moondog after a favorite pet that howled at the moon. His father was a traveling minister and occasional store owner who traveled around what was still a fairly wild West. Sometimes father and son encountered the drum music of the local Arapaho tribe, from which, Moondog told Michael Church of London's Sunday Telegraph, he learned "the running beat, and alongside it the walking beat, which is also the universal heartbeat." An Arapaho chief named Yellow-Cap or Yellow-Calf let him play a buffalo-skin drum during a ceremony. At Hurley High School in Missouri, Moondog played drums in the band. Later, when living in Germany, he wrote a number of marches.

The central experience of Moondog's youth came in Hurley, when he was 16: as he fooled with a stick of dynamite he had found on a railroad track, it exploded, blinding him in both eyes. After the accident, Moondog renounced his Christian faith: "I thought that if the God my father preached about was good, He wouldn't have let it happen to me," he told Steve Knowlton of Upstate magazine. He later turned toward the worship of ancient Norse gods. Moondog finished high school at the Iowa School for the Blind, picking up basic instruction in music theory and learning to play the pipe organ, violin, and viola. He later took classes in Braille at the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis, and learned the rare and extremely complex skill of writing Braille musical notation.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s Moondog lived in Arkansas and took more music classes in Memphis, furthering his musical education with Braille textbooks. In 1943, after learning that New York was the hub of American classical music activity, he made his way there. He was befriended by New York Philharmonic Orchestra conductor Artur Rodzinski, who let him listen in on orchestra rehearsals and promised to have the orchestra perform one of Moondog's symphonic compositions if he ever wrote one. Moondog's music became larger in scale, but Rodzinski stepped down as Philharmonic conductor in 1947. Fearing the outbreak of nuclear war, Moondog left New York the following year and headed West.

In the men's room of a police station in Salt Lake City, with help from some of the police on duty, Moondog built a set of square drums from old piano boards and some leather skins he got from a maker of artificial limbs. He later built several other instruments that were entirely of his own invention, including the oo, a triangular harp, and the uni, a drone instrument with seven piano-wire strings. By 1949 Moondog was back in New York, installed at his favorite panhandling roost on Sixth Avenue. A few times he was robbed or treated violently, but later he spoke fondly of the streets he had adopted as his home. "You get the impression New York is a cold, heartless place, but it's really not," he explained to Michael Small of People. "Taxi drivers and doormen look out for you." After he moved to Germany, Moondog told the New York Times that "New York City was my mother and father for 30 years."

Recordings were made of Moondog as early as 1950, and trained musicians who conversed with him quickly realized that they were dealing with more than an eccentric street person. Bebop jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker suggested to Moondog that they record together, and Moondog responded to news of the jazzman's untimely death by composing a new piece, "Bird's Lament." The famed Russian-French-American classical composer Igor Stravinsky testified on Moondog's behalf in the course of Moondog's ultimately successful lawsuit against disc jockey Allan Freed; the name of Freed's radio program "Moondog's Rock and Roll Party" helped give a new genre its name but, Moondog contended, the program used his name without his consent.

Eventually Moondog made recordings for two important record labels, Prestige in 1956 and 1957, and Columbia in 1969 and 1971. He agreed to make the first Columbia album only on condition that the label would not be able to review the album before its release. "Rare is the man who isn't bought," he observed to Upstate. With $750 in profits from the Prestige recordings, he bought a plot of land near the upstate New York town of Candor, south of Ithaca. He built a sod-and-stone shack and then a one-window, eight-by-sixteen-foot cabin insulated with tarpaper, sometimes staying there in the winter instead of enduring the cold on the New York streets. A small section of a table served as a workspace for the artist, who worked constantly on new music and poetry. He told Upstate in 1970 that he had at least ten albums' worth of music already written. He expressed a desire to go to Europe, telling the magazine that he considered himself a "European in exile."

Moondog wrote music of various kinds, but much of it can be grouped into several basic categories. He composed songs, and experienced a moment of popular success when blues-rock diva Janis Joplin recorded his "All Is Loneliness" on her album Big Brother and the Holding Company. (He complained to People, however, that she "really murdered it.") Moondog's classical compositions were mostly written for small ensembles, although he wrote some symphonies for full orchestra. His classical works, with their use of harmonically simple melodies undergirded by repetitions of small fragments of music, bore some similarities to the so-called minimalist music of composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich, and may have influenced it; Moondog met both Glass and Reich in New York in the 1960s.

Moondog's use of ambient or environmental sounds in his music also anticipated minimalist practices; his Prestige recordings were little portraits in tones of New York and of specific aspects of his environment. In other respects, however, his music diverged sharply from that of the minimalists. For example, he made use of the difficult technique of canon, in which statements of the same melodic material overlap in different parts or voices of a piece of music, and he once wrote a nine-hour canon in one thousand parts. Some of his works incorporated jazz influences, which the minimalists generally avoided. Moondog believed, however, that music should be fully written out, not improvised.

Over time, Moondog became something of a local celebrity in New York. He appeared with Mayor John Lindsay, performed with jazzman Charles Mingus at the Whitney Museum, and was interviewed on both the Today and Tonight television shows. In 1974, however, after traveling to Germany to conduct a concert of his works, Moondog stayed on. "I felt at home here, in the country where so many great composers have lived and worked," he explained to Adele Riepe of the New York Times. "I went to Bonn to the house where Beethoven was born. I sat at the spinet where he composed some of his great music and I felt I was in spiritual communication with him."

After a few months on the streets in Germany, Moondog met geology graduate student Ilona Goebel, who at the urging of her ten-year-old son invited him to move into her home in the small town of Oer-Werkenschwick in the industrial Ruhr Valley. "It was very logical," she told People. "I forgot about my university plans. We met, and this had to be done." Moondog agreed reluctantly but soon warmed to his new situation, telling Riepe that he was "living in a composer's paradise." He shed his Viking attire for simpler robes, or pants and a sweater.

Although Moondog had been married twice as a younger man and had one or two daughters, he and Goebel described their relationship only in professional terms, and she later married someone else. Goebel became Moondog's agent, musical transcriptionist, and librarian, making usable scores out of Moondog's Braille notation and persuading ensembles across Europe to perform his music. Moondog's popularity grew; he issued several albums (later collected in the boxed set Moondog: The German Years) and appeared in major European venues. His performance at London's Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1995 at a festival organized by iconoclastic rock songwriter Elvis Costello was a near-sellout.

Toward the end of his life, Moondog returned occasionally to the United States. He performed (often he played drums to accompany other musicians when he appeared live) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1989, and in 1998 he released Sax Pax for a Sax, his first American album since 1971, on the Atlantic label. "Each one of these songs leaves you feeling just a little bit more euphoric," wrote Newsweek reviewer Malcolm Jones Jr. "By the end of the album, you may need to be tethered to the floor." Moondog was pleased with his new celebrity, telling People that "there's no greater experience than to be wanted." He died of heart failure on September 8, 1999, in Münster, Germany, at age 83.

Selected discography:

-Moondog Prestige, 1956.

-More Moondog Prestige, 1956.

-The Story of Moondog Prestige, 1957.

-Moondog Columbia, 1969.

-Moondog 2 Columbia, 1971.

-Moondog in Europe Kopf, 1978.

-H'art Songs Kopf, 1979.

-The Music of Moondog (compilation), 1990.

-Sax Pax for a Sax Atlantic, 1997.

-Moondog: The German Years, 1977-1999 Roof, 2004.