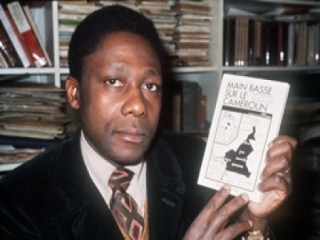

Mongo Beti biography

Date of birth : 1932-06-30

Date of death : -

Birthplace : M'balmayo, Cameroon

Nationality : Cameroonian

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-11-28

Credited as : novelist, French colonial world, Remember Ruben

Mongo Beti was one of the great Francophone novelists from Africa. His works satirize the French colonial world and dramatize the dilemmas of the quasi-Westernized African in acrid, sometimes ribald language and outrageous scenes.

Mongo Beti was born Alexandre Biyidi on June 30, 1932, in M'balmayo, a small village of the Beti people about 30 miles south of Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon. At 19 he received the baccalaureate from the lycee at Yaounde, and in 1951 he went to France on a scholarship to take advanced studies in literature, first at Aix-en-Provence and then at the Sorbonne in Paris. In 1966 he received the agregation, or teaching certificate, from the University of Paris.

While a student at Aix he wrote his first (now selfrepudiated) novel, Ville Cruelle (Cruel City), published in 1954 under the nom de plume Eza Boto. Considered a weak novel, it demonstrates strength in its melodramatic but often compelling naivete, and it well expresses the confusion experienced by the rural Africans crowding into the new industrial lumber and pulping town of Tanga South, "the kingdom of logs."

One of the major weaknesses of Ville Cruelle was its long, confessional monologues, but in his second novel, Le Pauvre Christ de Bomba (1956; The Poor Christ of Bomba), Beti mastered the exclamatory monologue to indict both France and the Church through the naive musings of the acolyte Denis, assistant to the well-meaning but ever obtuse Reverend Father Superior Drumont.

Mission Terminee (1957), Beti's third novel, is possibly one of his most successful and deeply humorous works. Again, his hero is a naïf whose initiation into life educates the reader into African verities as seen by an African. Here, however, the young Medza, having failed at the lycee, is initiated "backwards" into the life of the relatively untouched village of Kala, where his uncle's runaway wife has fled. Sent by his own village to reclaim her, Medza learns to appreciate and then to respect the older life and, more particularly, becomes willing to accept the help of his heroic-sized "country" cousin, Zambo. Though at the novel's close the two leave Kala and even Africa for a life of wandering, Medza has discovered that "the tragedy which our nation is suffering today is that of a man left to his own devices in a world which does not belong to him, which he has not made and does not understand."

Beti's fourth novel, Le Roi Miracule (1958; King Lazarus), confronts a powerful, pagan king with the missionary fervor of Le Guen, Drumont's vicar in the earlier years of The Poor Christ of Bomba. Though priding himself on being more astute and sensitive than the bumbling Drumont, Le Guen stirs up so much confusion and anger in the court of the king that the French Colonial Office has him recalled, for though Paris loves the Church it loves order and decorum much more.

Staunchly opposed to the foreign-controlled government in what was then French Cameroon, Beti moved to France. There, finding he could not support himself by writing, even with three well-received and increasingly popular novels to his credit, he turned to teaching, eventually gaining a professorship at a lycee in Rouen where he taught Latin, Greek, and French. A convinced Marxist, he refused to return to his native country even after it achieved independence in 1960. Despite professing himself anxious to visit Africa, he remained hostile to the Yaounde regime of President Ahmadou Ahidjo. Instead, Beti remained in France with his wife and their three children, and devoted himself to teaching for more than a decade.

In 1972 Beti published a political essay critical of the Yaounde government. Titled "The Plundering of Cameroon, the essay condemned Ahidjo and his officers as a puppet government of his country's former colonial rulers. The problems of decolonization would serve as the focus of the novels that Beti would once again begin to write.

In works that include Remember Ruben (1973) and Perpetua and the Habit of Unhappiness (1974), Beti turns a satirical eye upon the situation in the Cameroon, creating the fictitious dictator Baba Toura as the focus of his political satire. In Remember Ruben, a young orphan is take in by some villagers and befriended by a village boy. The two grow up and, though they part company for several years, eventually reunite; one as a revolutionary leader, and the other as a cast-off from an unjust society. The two characters would also serve as the subject of a 1979 work by Beti translated as Lament for an African Pol, which follows the effort of the two friends to start a revolt against the rule of unjust tribal chiefs. Perpetua and the Habit of Unhappiness also illustrates the inequities in postcolonial Cameroon through the lives of individuals, this time also depicting the lowly social status of that country's women. The novel would be adapted as a play in 1981.

Continuing to write from his self-imposed exile in France, Beti has woven his political concerns—particularly his concerns over continued French political influence in Cameroon—throughout his fiction. Like his novels of the 1970s and the 1980s, L'histoire du Fou (1994) illustrated the two economic and social levels of African society through the relationship between Zoaeteleu, a provincial village elder, and his son Narcisse, who is idealistic and in search of meaning in his life. Political repression shadows each of Beti's characters in the novel's complex plot as Zoaeteleu is falsely imprisoned without a trial and eventually released, only to find that his beloved son has been killed by an assassin—who turns out to be his own brother. As Robert P. Smith Jr. would note of L'histoire du Fou in World Literature Today, "Beti's reasoning, sometimes dead serious and sometimes familiarly humorous, is powerful, and his style, reminiscent of Balzac with its detailed descriptions and colorful images, and of Proust with its interminable sentences, remains superb."