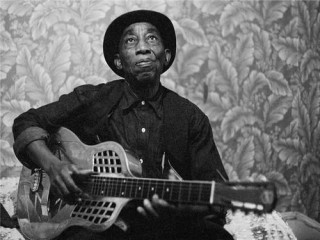

Mississippi John Hurt biography

Date of birth : 1893-03-08

Date of death : 1966-11-02

Birthplace : Teoc, Carroll County, Mississippi, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-12-01

Credited as : Country singer, guitarist, "Avalon Blues"

2 votes so far

John Hurt was born and lived most of his life in a remote corner of Mississippi Delta country. By the time he passed away, he had touched a generation of folk music fans and influenced countless guitar players interested in fingerpicking styles. He had two separate careers as a professional musician, separated by 35 years, and both must have seemed a little like a dream to him. When he was in his middle thirties, a recording contract fell in his lap out of nowhere, taking him to Memphis and New York. Within a year, the Great Depression hit and he slipped back into obscurity. But blues aficionados rediscovered Hurt in the early 1960s and he toured the country to great popular acclaim until his death in 1966.

Hurt was born in Teoc in Carroll County, Mississippi sometime between early 1892 and 1894, though March 8, 1892 is usually given as his date of birth. As a child he moved to Avalon, Mississippi where he was raised with seven brothers and two sisters. Hurt attended school until the fourth grade, long enough to learn to read and write. He grew up in a family of music lovers, and around the time he was nine his mother gave him a guitar which he taught himself to play using an intricate fingerpicking style in which the thumb played rhythm on the bass strings and three fingers played melody or chords.

Around 1910, Hurt played his first public performances. These were most likely parties or informal get-togethers of friends and neighbors who gathered to listen to music and relax. Blues historian Stephen Calt points out that Hurt probably did not play at dances like most other Mississippi bluesmen often did. His guitar style was too intricate to provide the insistent rhythm needed for dancing, and his singing was too restrained to cut through the noise of a Saturday night juke joint on the Delta.

During his early adult life, Hurt worked first as a sharecropper, then as a day laborer, which included five months laying train track. There, it is believed, he learned railroad songs like "Spike Driver Blues." Around 1923 Willie Narmour, a white farmer in Avalon who played fiddle at local square dances, asked Hurt to play with him when his regular guitarist could not. This was a remarkable tribute to Hurt's musical ability, considering the degree of racial segregation that existed in Mississippi at the time. A few years later, Narmour won a fiddling contest in Carroll County and attracted the attention of a scout for the Okeh record company, Tommy Rockwell.

Companies were combing the South, in the middle 1920s, looking for artists to record for the popular new medium of the phonograph. When Rockwell met Narmour in Avalon, he asked about other musicians in the area who might be good enough to make records. The fiddler told him about John Hurt and not long afterwards Narmour and Rockwell drove over to Hurt's house to set up an audition. Hurt played a song. Halfway through the second, Rockwell told him to stop, he had heard enough. Hurt was invited to go to Memphis for a recording session. On February 14, 1928, John Hurt became Mississippi John Hurt. He recorded eight songs and that same year, two of them were released on Okeh 8560, "Frankie" and "Nobody's Dirty Business"

What happened next is in dispute. Some writers say the record sold so well that Hurt was offered a second recording session; others say the record flopped, but that Rockwell was convinced that Hurt had something that would sell records. At any rate, in December 1928 John Hurt traveled to New York City where he recorded songs for five more 78s. Even though Hurt was in New York City for the first time in his life--it was only the second time he had traveled more than 20 miles from Avalon--even though he met Lonnie Johnson, the most popular blues guitarist in America, it was Christmas time and Hurt felt like a poor boy a long ways from home. He missed his wife, he missed Mississippi. In the last song recorded at the session, "Avalon Blues," he sings "Avalon's my home-town/always on my mind." That song would have enormous repercussions later in Mississippi John Hurt's life.

Hurt's records were a disappointment for Okeh, each selling only a few hundred copies. Some believe Okeh was ultimately responsible for their failure. First, they gave the records titles like "Candy Man Blues" and "Stack o' Lee Blues," when the songs had nothing in common with the true Mississippi blues being invented just a few miles from Hurt's front door. They were actually ragtime songs dating from an older folksong tradition. Second, because Hurt was not singing blues, because he came from the songster tradition, which was much closer to country music, he could have been popular among white audiences. Okeh, however, insisted upon listing his records in their "rac" catalog of exclusively black artists.

It was all moot anyway. Less than a year after Hurt's second recording session, the Great Depression hit America. The poor audiences at whom Hurt's kind of music was aimed, black and white alike, could no longer afford frivolities like records. Hurt just settled down with Jessie Lee, his second wife, back in Avalon. He raised a family, found worked regularly, played guitar around town when he could and forgot about any career in music--and was forgotten by the rest of the world in return.

Interest in Mississippi John Hurt reawoke in the early 1950s following the release of Harry Smith's monumental Anthology of American Folk Music . The six-record set included two Hurt songs "Frankie" and Spike Driver Blues" Like most of the musicians on the Anthology, Hurt was a mystery. In fact, most listeners, according to the notes included with the 1997 Anthology reissue, assumed that John Hurt was white. Guitar players, in particular, were fascinated with his fingerpicking style and struggled to learn the songs, first from the Anthology, and later off old 78 records that began resurfacing. According to one story, one of Andres Segovia's students brought a record by Hurt for the master to hear. After listening to Hurt, Segovia reportedly asked who was playing the second guitar on the song. Hurt played solo on all his recordings.

In the early 1960s, two young folk musicians in Washington, D.C., Tom Hoskins and Mike Stewart, heard "Avalon Blues" on a tape a record collector had given them. What if there was a city called Avalon in Mississippi, they wondered. And what if Hurt still lived there? They couldn't find Avalon on any contemporary maps, but the tiny town finally turned up in an atlas published in 1878. When they went to the Delta with their tape recorder, they discovered that Avalon wasn't much more than a general store on the road between Grenada and Greenwood. They asked some men sitting in front of the store if they had ever heard of a Mississippi John Hurt. One pointed and said "A mile down that road, third mailbox up. Can't miss it." When Hoskins and Stewart arrived, Hurt was out in the fields on his tractor. They introduced themselves, explained that they were interested in music, and pulled out their tape recorder.

From there Hurt's second career in music snowballed quickly. Back in Washington, Hoskins released two albums of songs he had recorded at Hurt's farm. Not long after, Hurt came to Washington to play local folk clubs. He was a smash at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival, and later the same year, at the Philadelphia Folk Festival. Suddenly, at age 71, Hurt was one of the top stars in the American folk music scene. For the next three years, he toured festivals and folk clubs throughout the country, released albums on the Piedmont and Vanguard labels--this time the records were very popular--and entranced fans with his broad repertoire of ballads, ragtime numbers, old pop tunes, and religious songs, his storytelling, and his gentle personality.

Hurt's fingerpicking style is unusual among black players of his time. Only Elizabeth Cotten--another self-taught guitarist--used a similar technique. Nonetheless his playing has had an enormous impact on guitar players from the 1960s onward and echoes of his playing can be heard in the work of musicians like Leo Kottke and Stefan Grossman. John Fahey, a player who took many of Hurt's techniques into uncharted, new realms, composed and recorded a moving tribute, "Requiem For Mississippi John Hurt," on his Vanguard album Requia . But Hurt's influence pervades all guitar playing. When beginning guitarists first begin to fingerpick, almost invariably the first tunes they learn are Hurt's, pieces like "Louis Collins" or "Stack O' Lee Blues."

John Hurt was unfazed by the abrupt end of his first career as a professional musician in 1929; at the end of his life he seemed equally undaunted by the stardom that had burst upon him, out of nowhere as far as he was concerned. Once asked if he knew how good his music was he answered almost with embarrassment. "Yeah ... I know it ... and I been knowin' it, but I never dreamed things would've turned out like they hav e... never dreamed it." Mississippi John Hurt died in Grenada, Mississippi on November 2, 1966.