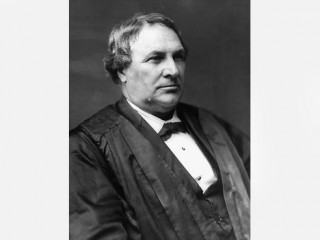

Miller Samuel Freeman biography

Date of birth : 1816-04-05

Date of death : 1890-10-13

Birthplace : Richmond, Kentucky, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-06-04

Credited as : Jurist and lawyer, Supreme Court, Abraham Lincoln

0 votes so far

In spite of the fact that he gained his legal training simply by reading law textbooks in his spare time, Samuel Freeman Miller became an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court. He served in that capacity for 28 years, from the time of his appointment by President Lincoln to his death in 1890, and wrote 616 opinions, the record for a Supreme Court justice at that time. As a jurist, Miller's career was characterized by a belief in a strong central government. Yet in many of his decisions concerning civil rights, he seems to have favored the position of letting the states govern themselves.

Education and Early Work

At the age of 12, Samuel first attended school in the town of Richmond, and during the latter part of his high school years worked at a local pharmacy. He established a lifelong pattern of self-education by setting out to study medicine on his own from textbooks, and when he was 20 he began formal training at the Transylvania University Department of Medicine in Lexington.

Two years later, Miller graduated and was qualified to practice medicine. He returned to Richmond and began his practice, then moved to Barboursville, further into the hinterlands of Appalachia. Only at that point, when he was about 30, did Miller realize he did not really want to be a doctor at all. Having participated in a local debate club, he knew what profession suited him best, and he started reading law books in his spare time. In 1847, at the age of 31--in an era when most lawyers began their practices in their early 20s--he was admitted to the bar.

Career

Miller quickly became involved in politics in general, and in the Whig party and the presidential campaign of Zachary Taylor in particular. But about the time Taylor was inaugurated in 1849, Miller, who found himself at odds with the party over the question of slavery, split with the Whigs. He left Kentucky the next year and settled in Keokuk, Iowa. The Republican party had begun to take the place of the Whigs, and Miller found its anti-slavery sentiments much more to his liking. He in turn impressed the party leadership, and in 1862 the new Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, appointed Miller to the Supreme Court.

During the Civil War, Justice Miller established himself as favoring strong federal government power. Thus he did not resist Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus in detaining prisoners, the trial of civilians before military courts, or the blockade of Southern harbors. In 1866, he expressed mild disapproval of those actions on the part of the federal government, but that was after the fact. In the postwar years, he continued to favor the power of government over individuals and groups, as in Cummings v. Missouri (1867) when he dissented from the majority's declaration that loyalty oaths for federal and state employees were unconstitutional. In Hepburn v. Griswold (1870), he again found himself outside of the majority, this time disagreeing with their opinion of paper money as unconstitutional; to Miller, Congress had full power under the Constitution to decide what was real money and what was not. The next year, when Knox v. Lee overturned the earlier case, Miller's opinion was confirmed as law.

In issues relating to Reconstruction and civil rights for all citizens, however, Miller proved less dedicated to the principle of a strong central government. The first major test of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed the protection of citizenship rights, came with the so-called Slaughterhouse Cases of 1873. The suit was brought by butchers in New Orleans, who complained that a butcher-shop monopoly established by the "carpetbag" government of Louisiana amounted to a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantees, implicit in which was the right to follow one's own vocation. The amendment, of course, like the Thirteenth and Fifteenth, which are lumped together as the "Reconstruction Amendments," had been intended to protect the rights of freed slaves, but these cases offered an opportunity to test the power of that amendment in a less controversial arena. In Miller's view at least, the Fourteenth Amendment did not "transfer the security and protection of all the civil rights...from the States to the Federal government."

This did not bode well for freed slaves, whose civil rights were in danger from precisely those state governments (in the South) whose power Miller had upheld. Nor did they have cause for encouragement when Miller joined the majority in their ruling on United States v. Cruikshank (1876), a case involving the killing of some 100 African Americans, again in Louisiana. Once again, the Court held that citizens should look to the states to protect their rights, something the states clearly were not going to do in this case. Similar cases followed. But his ruling in United States v. Reese, regarding the voting rights guaranteed in the Fifteenth Amendment, was more positive with regard to civil rights; the federal government, he suggested, had the power to prosecute anyone who interfered with someone else's voting rights. Miller sounded an even stronger note on this point in Ex parte Yarbrough (1884).

In Miller's later years, he saw what he considered a corruption of the intent of the Fourteenth Amendment, as the large and growing corporate monopolies in America began to use it to protect themselves. The Court itself did not help matters, since in 1886 it declared corporations to be "persons" protected under the amendment. He became more and more an advocate of regulation on big business, an action he called for in his opinion in Wabash v. Illinois (1886). When the centennial of the U.S. Constitution was celebrated in Philadelphia in September 1887, Miller was one of the keynote speakers. He died in Washington, D.C., three years later.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Education: Miller completed formal medical training at Transylvania University Department of Medicine in Lexington, Kentucky.