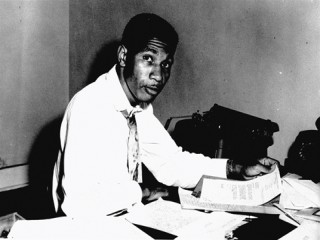

Medgar Evers biography

Date of birth : 1925-07-02

Date of death : 1963-06-12

Birthplace : Decatur, Mississippi, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-07-16

Credited as : Activist, ,

14 votes so far

The Mississippi in which Medgar Evers lived was a place of blatant discrimination where blacks dared not even speak of civil rights much less actively campaign for them. Evers, a thoughtful and committed member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), wanted to change his native state. He paid for his convictions with his life, becoming the first major civil rights leader to be assassinated in the 1960s. He was shot in the back on June 12, 1963, after returning late from a meeting. He was 37 years old.

Evers was featured on a nine-man death list in the deep South as early as 1955. He and his family endured numerous threats and other violent acts, making them well aware of the danger surrounding him because of his activism. Still he persisted in his efforts to integrate public facilities, schools, and restaurants. He organized voter registration drives and demonstrations. He spoke eloquently about the plight of his people and pleaded with the all-white government of Mississippi for some sort of progress in race relations. To those people who opposed such things, he was thought to be a very dangerous man. "We both knew he was going to die," Myrlie Evers said of her husband in Esquire. "Medgar didn't want to be a martyr. But if he had to die to get us that far, he was willing to do it."

In some ways, the death of Medgar Evers was a milestone in the hard-fought integration war that rocked America in the 1950s and 1960s. While the assassination of such a prominent black figure foreshadowed the violence to come, it also spurred other civil rights leaders--themselves targets of white supremacists--to new fervor. They, in turn, were able to infuse their followers--both black and white--with a new and expanded sense of purpose, one that replaced apprehension with anger. Esquire contributor Maryanne Vollers wrote: "People who lived through those days will tell you that something shifted in their hearts after Medgar Evers died, something that put them beyond fear.... At that point a new motto was born: After Medgar, no more fear."

Evers was born in 1925 in Decatur, Mississippi. He was the third of four children of a small farm owner who also worked at a nearby sawmill. Young Medgar grew up fast in Mississippi. His social standing was impressed upon him every day. In The Martyrs: Sixteen Who Gave Their Lives for Racial Justice, Jack Mendelsohn quoted Evers at length about his childhood. "I was born in Decatur here in Mississippi, and when we were walking to school in the first grade white kids in their schoolbusses would throw things at us and yell filthy things," the civil rights leader recollected. "This was a mild start. If you're a kid in Mississippi this is the elementary course.

"I graduated pretty quickly. When I was eleven or twelve a close friend of the family got lynched. I guess he was about forty years old, married, and we used to play with his kids. I remember the Saturday night a bunch of white men beat him to death at the Decatur fairgrounds because he sassed back a white woman. They just left him dead on the ground. Everyone in town knew it but never [said] a word in public. I went down and saw his bloody clothes. They left those clothes on a fence for about a year. Every Negro in town was supposed to get the message from those clothes and I can see those clothes now in my mind's eye.... But nothing was said in public. No sermons in church. No news. No protest. It was as though this man just dissolved except for the bloody clothes.... Just before I went into the Army I began wondering how long I could stand it. I used to watch the Saturday night sport of white men trying to run down a Negro with their car, or white gangs coming through town to beat up a Negro."

Evers was determined not to cave in under such pressure. He walked twelve miles each way to earn his high school diploma, and then he joined the Army during the Second World War. Perhaps it was during the years of fighting in both France and Germany for his and other countries' freedom that convinced Evers to fight on his own shores for the freedom of blacks. After serving honorably in the war he was discharged in 1946.

Evers returned to Decatur where he was reunited with his brother Charlie, who had also fought in the war. The young men decided they wanted to vote in the next election. They registered to vote without incident, but as the election drew near, whites in the area began to warn and threaten Evers's father. When election day came, the Evers brothers found their polling place blocked by an armed crowd of white Mississippians, estimated by Evers to be 200 strong. "All we wanted to be was ordinary citizens," he declared in Martyrs. "We fought during the war for America and Mississippi was included. Now after the Germans and the Japanese hadn't killed us, it looked as though the white Mississippians would." Evers and his brother did not vote that day.

What they did instead was join the NAACP and become active in its ranks. Evers was already busy with NAACP projects when he was a student at Alcorn A & M College in Lorman, Mississippi. He entered college in 1948, majored in business administration, and graduated in 1952. During his senior year he married a fellow student, Myrlie Beasley. After graduation the young couple moved near Evers's hometown and were able to live comfortably on his earnings as an insurance salesman.

Still the scars of racism kept accumulating. Evers was astounded by the living conditions of the rural blacks he visited on behalf of his insurance company. Then in 1954 he witnessed yet another attempted lynching. "[My father] was on his deathbed in the hospital in Union [Mississippi]," Evers related in Martyrs. "The Negro ward was in the basement and it was terribly stuffy. My Daddy was dying slowly, in the basement of a hospital and at one point I just had to walk outside so I wouldn't burst. On that very night a Negro had fought with a white man in Union and a white mob had shot the Negro in the leg. The police brought the Negro to the hospital but the mob was outside the hospital, armed with pistols and rifles, yelling for the Negro. I walked out into the middle of it. I just stood there and everything was too much for me.... It seemed that this would never change. It was that way for my Daddy, it was that way for me, and it looked as though it would be that way for my children. I was so mad I just stood there trembling and tears rolled down my cheeks."

Evers quit the insurance business and went to work for the NAACP full-time as a chapter organizer. He applied to the University of Mississippi law school but was denied admission and did not press his case. Within two years he was named state field secretary of the NAACP. Still in his early thirties, he was one of the most vocal and recognizable NAACP members in his state. In his dealings with whites and blacks alike, Evers spoke constantly of the need to overcome hatred, to promote understanding and equality between the races. It was not a message that everyone in Mississippi wanted to hear.

The Evers family--Medgar, Myrlie and their children--moved to the state capital of Jackson, where Evers worked closely with black church leaders and other civil rights activists. Telephone threats were a constant source of anxiety in the home, and at one point Evers taught his children to fall on the floor whenever they heard a strange noise outside. "We lived with death as a constant companion 24 hours a day," Myrlie Evers remembered in Ebony magazine. "Medgar knew what he was doing, and he knew what the risks were. He just decided that he had to do what he had to do. But I knew at some point in time that he would be taken from me."

Evers must have also had a sense that his life would be cut short when what had begun as threats turned increasingly to violence. A few weeks prior to his death, someone threw a firebomb at his home. Afraid that snipers were waiting for her outside, Mrs. Evers put the fire out with the garden hose. The incident did not deter Evers from his rounds of voter registration nor from his strident plea for a biracial committee to address social concerns in Jackson. His days were filled with meetings, economic boycotts, marches, prayer vigils, and picket lines--and with bailing out demonstrators arrested by the all-white police force. It was not uncommon for Evers to work twenty hours a day.

Some weeks before his death, Evers delivered a radio address about the NAACP and its aims in Mississippi. "The NAACP believes that Jackson can change if it wills to do so," he stated, as quoted in Martyrs. "If there should be resistance, how much better to have turbulence to effect improvement, rather than turbulence to maintain a stand-pat policy. We believe that there are white Mississippians who want to go forward on the race question. Their religion tells them there is something wrong with the old system. Their sense of justice and fair play sends them the same message. But whether Jackson and the State choose to change or not, the years of change are upon us. In the racial picture, things will never be as they once were."

On June 11, 1963, U.S. president John F. Kennedy--who would be assassinated only a few short months later--echoed this sentiment in an address to the nation. Kennedy called the white resistance to civil rights for blacks "a moral crisis" and pledged his support to federal action on integration.

That same night, Evers returned home just after midnight from a series of NAACP functions. As he left his car with a handful of t-shirts that read "Jim Crow Must Go," he was shot in the back. His wife and children, who had been waiting up for him, found him bleeding to death on the doorstep. "I opened the door, and there was Medgar at the steps, face down in blood," Myrlie Evers remembered in People magazine. "The children ran out and were shouting, 'Daddy, get up!'"

Evers died fifty minutes later at the hospital. On the day of his funeral in Jackson, even the use of beatings and other strong-arm police tactics could not quell the anger among the thousands of black mourners. The NAACP posthumously awarded its 1963 Spingarn medal to Medgar Evers. It was a fitting tribute to a man who had given so much to the organization and had given his life for its cause.

Rewards were offered by the governor of Mississippi and several all-white newspapers for information about Evers's murderer, but few came forward with information. However, an FBI investigation uncovered a suspect, Byron de la Beckwith, an outspoken opponent of integration and a founding member of Mississippi's White Citizens Council. A gun found 150 feet from the site of the shooting had Beckwith's fingerprint on it. Several witnesses placed Beckwith in Evers's neighborhood that night. On the other hand, Beckwith denied shooting Evers and claimed that his gun had been stolen days before the incident. He too produced witnesses--one of them a policeman--who swore before the court that Beckwith was some 60 miles from Evers's home on the night he was killed.

Beckwith was tried twice in Mississippi for Evers's murder, once in 1964 and again the following year. Both trials ended in hung juries. Sam Baily, an Evers associate, commented in Esquire that during those years "a white man got more time for killing a rabbit out of season than for killing a Negro in Mississippi."

After the second trial, Myrlie Evers took her children and moved to California, where she earned a degree from Pomona College and was eventually named to the Los Angeles Commission of Public Works. However, her conviction that justice was never served in her husband's case kept Mrs. Evers involved in the search for new evidence. As recently as 1991, Byron de la Beckwith was arrested a third time on charges of murdering Medgar Evers. Beckwith was extradited to Mississippi to await trial again, still maintaining his innocence and still committed to the platform of white supremacy.

Perhaps the most encouraging aspect of Medgar Evers's story lies in the attitudes of his two sons and one daughter. Though they experienced firsthand the destructive ways of bigotry and hatred, Evers's children appear to be very well-adjusted individuals. "My children turned out to be wonderfully strong and loving adults," Myrlie Evers concluded in Ebony. "It has taken time to heal the wounds [from their father's assassination] and I'm not really sure all the wounds are healed. We still hurt, but we can talk about it now and cry about it openly with each other, and the bitterness and anger have gone."

At the same time, Mrs. Evers asserted in People that she hopes for Beckwith's conviction on the murder charges. "People have said, 'Let it go, it's been a long time. Why bring up all the pain and anger again?'" she explained. "But I can't let it go. It's not finished for me, my children or ... grandchildren. I walked side by side with Medgar in everything he did. This [new] trial is going the last mile of the way."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born Medgar Riley Evers, 1925, in Decatur, MS; died of internal injuries from a gunshot wound to the back, June 12, 1963; son of a farmer and sawmill employee and a homemaker; married Myrlie Beasley, December 24, 1951; children: Darrell Kenyatta, Reena Denise, James Van Dyke. Education: Alcorn A & M College, Lorman, MS, B.A., 1952. Military/Wartime Service: U.S. Army, 1943-46; served in Europe.

AWARDS

Spingarn medal, NAACP, 1963 (posthumous).

CAREER

Insurance salesman and chapter organizer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), 1952-54; state field secretary for the NAACP, 1954-63.