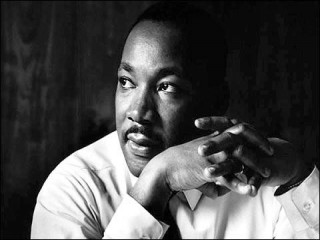

Martin Luther King, Jr. biography

Date of birth : 1929-01-15

Date of death : 1968-04-04

Birthplace : Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-04-09

Credited as : American activist and leader, African American civil rights movement, Nobel Peace Prize

84 votes so far

In Boston, King met Coretta Scott, whom he married on June 18, 1953. They had four children. King became minister of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1954, and became active with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Alabama Council on Human Relations.

In December 1955, Rosa Parks, a black woman, was arrested for violating a segregated seating ordinance on a public bus in Montgomery, thus initiating a series of protests which ultimately led to the boycott the segregated city buses and the formation of Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). The boycott lasted over a year, until the bus company capitulated. Segregated seating was discontinued, and some African Americans were employed as bus drivers.U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that the bus segregation laws of Montgomery as unconstitutional.

In January 1957 approximately sixty black ministers in Atlanta formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). A few months later King met Vice President Richard Nixon, and a year later King and three other black civil rights leaders were received by President Dwight Eisenhower. However, neither meeting resulted in any concrete relief for African Americans.

In February 1958 the SCLC resolved to double the number of southern black voters. King traveled constantly, speaking for justice, and he and his wife visited India at the invitation of Prime Minister Nehru. King had long been interested in Mahatma Gandhi's practice of nonviolence. Yet when they returned to the United States, the civil rights struggle had intensified.

In 1960 King became minister of his father's church in Atlanta. The sit-in movement began in Greensboro, North Carolina, by African American students protesting segregation at lunch counters in city stores. King urged the young people to continue using nonviolent means. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) emerged, and for a time the SNCC worked closely with the SCLC.

By August sit-ins had succeeded in ending segregation at lunch counters in 27 southern cities. SCLC delegates resolved to focus nonviolent campaigns against all segregated public transportation, waiting rooms, and schools; to increase emphasis on voter registration; and to use economic boycotts to gain fair employment and benefits.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), SCLC, and SNCC joined in a coalition. A Freedom Ride Coordinating Committee was formed with King as chairman. The idea was to "put the sit-ins on the road" by having pairs of black and white volunteers board interstate buses traveling through the South to test compliance with a new federal law. Finally, nonsegregation laws were followed in buses engaged in interstate transportation and in their terminals.

In an ambitious voter education program in Albany and the surrounding area, SNCC and SCLC members were harassed by whites. Churches were bombed, and local black citizens were threatened and sometimes attacked. King's nonviolent crusade responded with prayer vigils. The 1964 Federal Civil Rights Act finally desegregated public facilities in Albany.

In May 1962 King took on the Birmingham, Alabama, campaign. In early 1963 King made a speaking tour, recruiting volunteers and obtaining money for bail bonds. The SCLC's campaign continually met harassment from Birmingham police. Finally, a period of truce was established, and negotiations began with the city power structure. Though an agreement was reached, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the home of King's brother and the motel where SCLC members were headquartered.

On August 27, 1963, over 250,000 black and white citizens assembled in Washington, D.C., for a mass civil rights rally, where King delivered his famous "Let Freedom Ring" address. That same year he was featured as Time magazine's "Man of the Year."

The next year King and his followers moved into St. Augustine, Florida, where after weeks of nonviolent demonstrations and violent counterattacks, a biracial committee was set up to move St. Augustine toward desegregation. A few weeks later the 1964 Civil Rights Bill was signed by President Lyndon Johnson.

In September 1964 King received an honorary doctorate from the Evangelical Theological College in Berlin. Back in the United States, King endorsed Lyndon Johnson's presidential candidacy. That December, King received the Nobel Peace Prize.

In 1965 the SCLC concentrated its efforts in Alabama. The prime target was Selma. King announced a march from Selma to Montgomery to demonstrate the black people's determination to vote. But Governor George Wallace refused to permit it. But the march continued. Twenty-five thousand met in Montgomery for the march to the capital to present a petition to Wallace.

In 1967 King began speaking directly against the Vietnam War, and he also announced that the Poor People's March would converge in Washington in April. Following the February rally, King toured key cities to see firsthand the plight of the poor. Meanwhile, in Memphis, black sanitation workers were striking, and protests generalized to grievances ranging from police brutality to intolerable school conditions. In March, Memphis demonstrations ended in a riot. In Memphis on April 3, King addressed a rally; speaking of threats on his life, he urged followers to continue the nonviolent struggle no matter what happened to him.The next evening, as he stood on an outside balcony at the Lorraine Hotel, King was assassinated. In December 1999, a four-acre site near the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., was approved as the location for a monument to King. The site is near the place where King delivered his "I have a dream" speech in 1963. The monument will be the first to honor an individual black American in the National Mall area.

On March 29, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee in support of the black sanitary public works employees, represented by AFSCME Local 1733, who had been on strike since March 12 for higher wages and better treatment. In one incident, black street repairmen received pay for two hours when they were sent home because of bad weather, but white employees were paid for the full day.

King was booked in room 306 at the Lorraine Motel, owned by Walter Bailey, in Memphis. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, King's close friend and colleague who was present at the assassination, swore under oath to the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations that King and his entourage stayed at room 306 at the Lorraine Motel so often it was known as the "King-Abernathy suite."

According to Jesse Jackson, who was present, King's last words on the balcony prior to his assassination were spoken to musician Ben Branch, who was scheduled to perform that night at an event King was attending: "Ben, make sure you play "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" in the meeting tonight. Play it real pretty."

Then, at 6:01 p.m., April 4, 1968, a shot rang out as King stood on the motel's second floor balcony. The bullet entered through his right cheek, smashing his jaw, then traveled down his spinal cord before lodging in his shoulder. Abernathy heard the shot from inside the motel room and ran to the balcony to find King on the floor. The events following the shooting have been disputed, as some people have accused Jackson of exaggerating his response.

After emergency chest surgery, King was pronounced dead at St. Joseph's Hospital at 7:05 p.m. According to biographer Taylor Branch, King's autopsy revealed that though only thirty-nine years old, he had the heart of a sixty-year-old man, perhaps a result of the stress of thirteen years in the civil rights movement.

The assassination led to a nationwide wave of riots in more than 100 cities. Presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was on his way to Indianapolis for a campaign rally when he was informed of King's death. He gave a short speech to the gathering of supporters informing them of the tragedy and asking them to continue King's idea of non-violence. President Lyndon B. Johnson declared April 7 a national day of mourning for the civil rights leader. Vice-President Hubert Humphrey attended King's funeral on behalf of Lyndon B. Johnson, as there were fears that Johnson's presence might incite protests and perhaps violence. At his widow's request, King's last sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church was played at the funeral. It was a recording of his "Drum Major" sermon, given on February 4, 1968. In that sermon, King made a request that at his funeral no mention of his awards and honors be made, but that it be said that he tried to "feed the hungry", "clothe the naked", "be right on the [Vietnam] war question", and "love and serve humanity". His good friend Mahalia Jackson sang his favorite hymn, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord", at the funeral. The city of Memphis quickly settled the strike on terms favorable to the sanitation workers.

Two months after King's death, escaped convict James Earl Ray was captured at London Heathrow Airport while trying to leave the United Kingdom on a false Canadian passport in the name of Ramon George Sneyd on his way to white-ruled Rhodesia. Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's murder. He confessed to the assassination on March 10, 1969, though he recanted this confession three days later. On the advice of his attorney Percy Foreman, Ray pleaded guilty to avoid a trial conviction and thus the possibility of receiving the death penalty. Ray was sentenced to a 99-year prison term. Ray fired Foreman as his attorney, from then on derisively calling him "Percy Fourflusher". He claimed a man he met in Montreal, Quebec with the alias "Raoul" was involved and that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy. He spent the remainder of his life attempting (unsuccessfully) to withdraw his guilty plea and secure the trial he never had. On June 10, 1977, shortly after Ray had testified to the House Select Committee on Assassinations that he did not shoot King, he and six other convicts escaped from Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary in Petros, Tennessee. They were recaptured on June 13 and returned to prison.