Marlon Brando biography

Date of birth : 1924-04-03

Date of death : 2004-07-01

Birthplace : Omaha, Nebraska, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-06-16

Credited as : Movie actor, Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967),

1 votes so far

Brando, nicknamed Bud, was the third of the three children of Dorothy (“Dodie”) Pennebaker Brando, an amateur actress, and Marlon Brando, Sr., a traveling salesman. Brando was close to his mother but had an animosity toward his harsh, remote father. Brando’s parents, both alcoholics, had an embattled relationship, frequently separating and reuniting.

An indifferent and often misbehaving student, Brando was expelled from a number of schools. In 1941 his father sent Brando to his alma mater, the Shattuck Military Academy, in Faribault, Minnesota. Defying his teachers and often fighting with other students, Brando resisted the discipline that the academy attempted to impose. His one success was his appearance in three one-act plays, in which he demonstrated a talent for mimicry and disguise. In May 1943, after repeated refusals to conform to school regulations, Brando was expelled. He did not graduate from high school.

In the summer of 1943 Brando moved to New York City, mostly because his two sisters were living there. Because one of his sisters was pursuing an acting career, Brando decided to explore the theater as well. He enrolled in the dramatic workshop of the New School for Social Research. There Brando met Stella Adler, a legendary acting teacher who immediately recognized his gifts.

In the summer of 1944 Brando appeared in summer stock theater in Sayville, Long Island, New York. He played the double role of a young Christ and an enfeebled elderly schoolmaster in Gerhart Hauptmann’s Hannele’s Way to Heaven. The MCA talent agency, impressed by Brando’s skill in self-transformation, signed the actor and that fall sent him on many auditions. On 19 October 1944 Brando made his Broadway debut as the fifteen-year-old son in a Norwegian-American family in I Remember Mama by John Van Druten. Critics and audiences responded at once to Brando’s striking looks and charismatic naturalness, the sense that he did not seem to be acting.

Adler encouraged her husband, the director Harold Clurman, to cast Brando in Truckline Cafe by Maxwell Anderson. Brando played a World War II veteran who kills his unfaithful wife and then in a five-minute monologue confesses to the crime. On opening night, 27 February 1944, Brando’s electrifying delivery of the monologue stopped the show. Other stage roles, including March-banks in a 1946 production of George Bernard Shaw’s Candida, followed quickly.

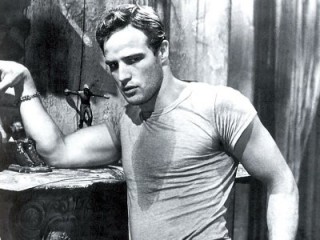

On 3 December 1947 Brando opened on Broadway as Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, directed by Elia Kazan. Although Stanley is supposed to be the play’s heavy—a brute realist locked in mortal battle for his wife, Stella, with Stella’s high-toned sister, Blanche Du Bois, who is addicted to illusion and masquerade—audiences rooted for Stanley and often laughed at Blanche, played by Jessica Tandy. The reaction surprised and delighted Williams.

In the fall of 1947 Brando had begun attending sessions at the Actors Studio, the home of the Method acting technique. As he had throughout rehearsals for Streetcar, Brando admired the ability of Kazan, one of the cofounders of the studio, to establish immediate intimacy with actors. When the acting teacher Lee Strasberg, a bitter enemy of Adler’s, began to moderate sessions in 1949, Brando became disenchanted with the studio and left.

Brando relocated to Hollywood in late 1949. Rather than signing a standard seven-year contract with a major studio, Brando made a one-picture deal with Stanley Kramer, an independent producer who offered him the role of a paraplegic veteran in The Men (1950). To prepare for the role, Brando, pretending to be unable to walk, checked into a hospital, where he could make first-hand observations. In his second film Brando collaborated again with Kazan to play Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). Brando’s slurred, mumbled speech pitted with pauses and broken sentences; his loaded silences; his hunched and potentially threatening body language; his suggestions of his character’s coiled, vibrant inner life; his flights of corrosive humor and rage; and his volcanic sexuality set a new standard for psychological realism in American film acting. For the film Kazan was careful to cast a Blanche Du Bois who was worthy of Brando’s performance. Vivien Leigh’s tremulous and ultimately tragic characterization evoked no laughter in movie audiences.

After Streetcar, Brando was in a position to play the roles he wanted to, and in his next three films he chose material that showed his range as well as his determination to defy typecasting. In Viva Zapata! (1952), directed by Kazan, with dark makeup and a sketchy attempt at vocal disguise Brando plays a mercurial Mexican revolutionary. As Marc Antony in MGM’S all-star Julius Caesar (1953) Brando was more successful in banishing traces of Stanley Kowalski. Uncertain of his ability to perform Shakespeare with a cast of veterans, Brando relied on his skills in mimicry and prepared by studying the actor Laurence Olivier’s recordings of the works of Shakespeare. As the rebel in The Wild One (1953) Brando projected a combination of muscularity and sensitivity, and the image of the actor riding a motorcycle dressed in jeans and leather became an icon of 1950s America.

On the Waterfront (1954), Brando’s final collaboration with Kazan, was the high point of his career. The film’s drama is an inner one: what Terry Malloy, a former prize-fighter who works on the crime-ridden Hoboken waterfront, is thinking and feeling as he gradually arrives at self-knowledge. For most of the film there is a split between the character’s words and his thoughts, and Brando filled the gaps between speech and action with a palpitating subtext. Malloy’s turbulent inner monologue is registered in Brando’s body language, his roving, distracted eye movements, and his strangled speech patterns, which reflect the struggle of an inarticulate character to find the words to match his feelings. Brando won his first Academy Award for this performance, which has been cited as the quintessential example of the inner-directed Method style.

After On the Waterfront, Brando refused to repeat Stanley Kowalski or Terry Malloy and refused to play the role of star that the press expected of him. As his fame grew, Brando became an uncooperative celebrity. He received bad publicity for two tempestuous, short-lived marriages. On 11 October 1957 he wed Anna Kashfi, an actress. The couple had one son and divorced in 1959. On 4 June 1960 Brando married the Mexican actress Movita Castaneda, with whom he had one son. The couple divorced in 1962.

From 1955 to 1960 Brando’s films were of uneven merit, but his work was filled with invention. In Desirée (1954), Brando played Napoleon as a fop with a crisp British accent. In Guys and Dolls (1955) he took on the challenge of musical comedy, singing in his own voice to play the gambler Sky Masterson. In Teahouse of the August Moon (1956), Brando played a wily Japanese interpreter. Brando changed the ending of Sayonara (1957) so that his character, a southern military man, marries a Japanese performer. His revision underscored the change of heart that Brando looked for in his characters and provided the kind of social comment to which he was increasingly drawn. Brando also altered his role of an ardent Nazi in The Young Lions (1958). Searching for the kind of arc that ignited his instincts, Brando portrayed the character as becoming gradually disillusioned with the Nazi cause. His performance as a drifter in The Fugitive Kind (1960) failed because Brando was unable to discover change in the character, a stud who ignites passionate responses in others while remaining passive.

With One-Eyed Jacks (1961), the only film Brando directed, and Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), the actor became a victim of his reputation for being difficult. On both projects Brando was accused of causing lengthy production delays and of being responsible for hefty cost overruns. During the shooting of Bounty, Brando began a relationship with his co-star, Tarita Teriipia, whom he married on 10 August 1962 and to whom he was married at the time of his death. He also became attached to Tahiti, buying his own Pacific island, the atoll Teti’aroa.

After Bounty, Brando appeared in numerous unsuccessful films, including Bedtime Story (1964), a clumsy farce, and The Countess from Hong Kong (1967), in which he was unhappily directed by Charles Chaplin, who insisted on giving line readings and demonstrating movements that he expected Brando to imitate. During this period in which he was repeatedly charged with having forsaken his talent and his audience, Brando appeared in Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). As a repressed homosexual officer in a southern military outpost, the actor gave an extraordinary performance that was subtle, rapt, and intuitive. When the film failed, Brando began to make frequent statements about his contempt for acting. Also in the late 1960s Brando became active in civil rights causes. For a time he endorsed the Black Panthers, some of whom resented his fame and questioned his motives.

Brando returned to form playing Don Corleone in The Godfather (1972), his most skillfully conceived disguise. His face and voice cracking with age, the actor created a character built of sharp contradictions: as he plans mass murders the don softly strokes a cat; before his death the don plays with his grandson in a spirit of childlike innocence. For his performance Brando received, and famously refused, a second Academy Award. On Oscar night he sent a representative to read a speech he had written about the plight of American Indians.

Brando followed his greatest disguise performance with his most generous act of self-revelation. As Paul in The Last Tango in Paris (1972) Brando played a tortured character who has ferocious sexual encounters with a woman whose name he never knows. Encouraged by his director, Bernardo Bertolucci, to improvise, Brando drew on his own experiences, and the performance was laced with the actor’s memories of his childhood, his marriages, and his promiscuity. After Last Tango, Brando never again played a central role or one that demanded much of his emotional resources. Although his films after Tango were rarely more than routine, Brando’s work had variety and the imprint of a born actor’s inspiration. In the minor Western The Missouri Breaks (1976), for example, Brando appeared in an assortment of disguises and used a range of accents.

As his weight swelled Brando became ever more reclusive and erratic. In May 1990 his privacy was shattered when his son Christian killed his half-sister Cheyenne’s boyfriend. To protect his son and to deflect attention from the trial, Brando was gregarious with the news media. Christian, who claimed the shooting was accidental, was sentenced to prison, and Cheyenne committed suicide in 1995. For a sizable advance Brando in 1994 broke his silence with the memoir Songs My Mother Taught Me, written with Robert Lindsey. Although he makes no reference to his eleven children (three of whom he adopted and three of whom were by his former housekeeper Christina Maria Ruiz), Brando is frank about his sexual history and about his coworkers. Fan-Tan (2005) is a posthumous novel written by Brando in collaboration with Donald Cammell. The protagonist, who conquers and betrays exotic women and lives a bohemian life outside the law, is a revealing self-portrait.

Over the years it became apparent that Brando was disturbed and self-destructive. Despite decades of therapy he never resolved his feelings about his father or accepted his gifts as an actor, yearning instead for prominence as a social thinker and activist, public roles for which he was unqualified. Brando died of pulmonary fibrosis on 1 July 2004. His body was cremated and the ashes spread in Death Valley, California, and Tahiti. At the time of his death Brando had become a nearly 400-pound recluse. He was, however, one of the most influential actors in the history of American film. At least five of his performances—in A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, Reflections in a Golden Eye, The Godfather, and Last Tango in Paris—are milestones in the history of acting.

Peter Manso, Brando: The Biography (1994), is highly critical. Patricia Bosworth, Marlon Brando (2001), is a concise overview of the actor’s life. Obituaries are in the New York Times and San Francisco Chronicle (both 3 July 2004).