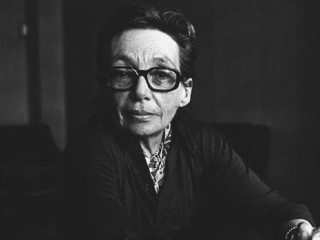

Marguerite Duras (En.) biography

Date of birth : 1914-04-04

Date of death : 1996-03-03

Birthplace : Gia Dinh, Vietman

Nationality : French

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-08-20

Credited as : Writer and novelist, movie producer, playwright

1 votes so far

Marguerite Duras was one of France's most famous writers of the twentieth century. Her talents ranged across fiction, film, playwriting, and journalism, and all through her long career, just the mention of her name could be counted on to start a spirited discussion in a Parisian café or in an American or English college literature or women's studies department. A compulsive worker, Duras wrote 34 novels and a wide variety of shorter works, returning to writing even after a stroke robbed her of the use of her dominant hand.

Duras revealed her own tumultuous experiences in many of her writings, but she used fiction to disguise, dig into the underlying motivations behind, or elaborate upon actual events. She wove the clues of her own life into her writings, but her public utterances contradicted one another and tied biographers in knots. Key episodes in her early life are subjects of dispute, and Duras' own outspokenness and intensity made it hard to know when to take her statements at face value. Yet the dance of veils choreographed by Duras' fiction and public image was all part of her appeal. Duras was a daring innovator, using fiction to view the events of her life through a constantly changing set of lenses.

Spoke Fluent Vietnamese

Duras retold the events of her early life over and over again in her books. She was born Marguerite Donnadieu on April 4, 1914, in Gia Dinh, near Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) in the French colony of Indochina, now the country of Vietnam. As a young woman she learned to speak Vietnamese fluently, and, except for two years she spent at a family home near the town of Duras in southwestern France, she grew up in southeast Asia. Her father, a math teacher, died when she was four.

After Henri Donnadieu's death, Duras' mother Marie tried to put the family on a solid financial footing by buying a rice plantation on the coastline of what is now Cambodia. She was swindled, however, by corrupt officials in the French colonial government, and she found that the land she had acquired was so often swamped by seawater that it was unsuitable for farming. Repeated unsuccessful attempts to build a seawall further drained the family's savings. Duras attended high school in Saigon, but finances had declined to a point where she found herself poorer than many of her Asian classmates.

Encouraged by her mother, Duras embarked on a romantic and sexual liaison with a wealthy Asian man. One of Duras' many biographers, Laure Adler, working from an unpublished Duras diary, has asserted that Duras was essentially sold into prostitution by her mother in order to finance the drug habit of her brother Pierre, but this characterization of events has been strongly disputed by her son, Jean Mascolo. Both the affair and the family battle with the encroaching ocean would recur as motifs in Duras' writing.

That writing career would take more than a decade to get underway. Duras moved alone to France in 1932 and was admitted to the Sorbonne, a prestigious university in Paris. She studied law, political science, and mathematics there, and after she received her degree in 1935 she took a job with the Ministry of Colonies, working for the same bureaucracy that had cheated her mother out of the family inheritance. As with so many other aspects of her life, controversy has attended Duras' work during this period; using the name Marie Donnadieu, she penned a propaganda volume that laid out justifications for France's colonial adventures in Asia. It may be, however, that she was acting as a ghostwriter for a higher official. In 1939 Duras married a writer, Robert Antelme. The couple's first child was stillborn in 1942.

Became Involved with French Resistance

Duras' actions during World War II are likewise uncertain. Adler's biography claims that she worked for the Nazi puppet government in Vichy, France as a de facto censor, controlling the distribution of paper in occupied France. This claim, too, has been disputed by Mascolo. It is clear, however, that World War II turned Duras' life upside down, causing her to reevaluate her earlier life and present situation. She struck out in new directions both politically and artistically. By 1943, Duras was working for the French anti-Nazi resistance, and her first novel, Les impudents (The Impudent Ones) was published that year.

The head of her resistance cell was a man she knew as Morland who later became better known as François Mitterand, president of France for 14 years beginning in 1981. Duras herself narrowly escaped arrest by the Nazis, but her husband and sister-in-law were seized and sent to concentration camps. She claimed to have once saved Mitterand's life, and German rule fell apart toward the war's end with the advance of American troops, Mitterand returned the favor, finding Antelme near death in the Dachau camp and rescuing him.

Meanwhile, Duras' literary career had begun to rise from the ashes of war. Les impudents dealt with a fictionalized version of her family's part-time hometown of Duras, and she soon adopted the town's name as her own. Her second novel, La vie tranquille (The Tranquil Life, 1944), was also set in Duras, and the two novels both featured a negative mother figure whom Duras would revisit in various ways in many later writings. La vie tranquille attracted the attention of writer Raymond Queneau, who shepherded the book toward publication at the prestigious Gallimard house in Paris.

After the war, Duras joined the Communist party but resigned her membership in 1950 upon finding Communist doctrine too restrictive. She helped nurse Antelme back to health but also began an affair with writer Dionys Mascolo. For a time the three lived as a ménage à trois, and Mascolo became the father of Duras' only son, Jean Mascolo. Duras scored a critical breakthrough in 1950 with the publication of her novel Un barrage contre le Pacifique (translated as The Sea Wall), which was drawn on her family's experiences in Indochina.

Wrote Prescient Essay

Duras wrote voluminously in the 1950s, venturing into journalism as well as fiction. As her reputation grew, she became one of France's most familiar public intellectuals, quick with a sharp opinion even if she might sometimes contradict herself. "I think the future belongs to women," Duras said in an interview quoted in Women Filmmakers and Their Films. "Men have been completely dethroned. Their rhetoric is stale, used up. We must move on to the rhetoric of women, one that is anchored in the organism, in the body." Yet she also once said, according to the Scotsman, that "I am in favor of total submission to men. This is how I've got everything I wanted."

Some of Duras' early novels were sprawling, detailed narratives influenced in part by the expansive style of American writer Ernest Hemingway, but gradually she came under the influence of modernist trends. She won praise for the 1955 novel Le square and for 1958's Moderato cantabile, both composed nearly entirely of dialogue that seems to circulate around the edges of unspoken events. In 1959, leading French film director Alain Resnais asked Duras to write a screenplay for him. Although Duras had done little dramatic writing, Hiroshima, mon amour became one of the most celebrated films of all time. The story of a love affair between a French actress and a Japanese architect in Tokyo during World War II, the film juxtaposed a world of private feelings with the overwhelming tragedy of war.

Duras went on to make numerous short films of her own in the 1960s and 1970s, often working on a shoestring budget and using her own Paris apartment as a set. Although she was less well known as a director than other prominent French experimentalists of the day, her work attracted the attention of young film industry figures such as actor Gérard Depardieu, who played a truck driver in the film Le camion (The Truck). The film consisted of a single one-hour-and-twenty-minute conversation between a truck driver and a female hitchhiker, played by Duras herself. Her 1975 film India Song was a more elaborate production that won the grand prize of France's Cinema Academy.

The author of a number of plays between 1960 and the late 1980s, Duras continued to write novels at a steady pace. Many of them dealt with themes of love and passion. Her greatest success came at age 70 with L'amant (The Lover, 1984), which won France's top literary honor, the Goncourt Prize. In 1992 the novel was filmed by director Jean-Jacques Annaud; the film, at first condemned but later embraced by Duras, became internationally successful.

Returned to Scenes from Youth

L'amant succeeded in tying together many of the themes and techniques Duras had explored over her long career. Minimalistically told like many of her later novels, the novel took Duras' youthful affair with her Asian lover for its subject matter. Viewed in one way, it was part of an effort at self-revelation that Duras made as she looked back on her life; biographies of Duras had begun to appear, and she revealed more and more of her secrets to literary scholars. Sometimes, however, her revelations created more mysteries than they clarified. Another autobiographical work, La douleur (1985, translated as The War: A Memoir), traced Duras' experiences during World War II. Literary scholars have debated the levels of truth versus fiction in both books.

A heavy consumer of alcohol for much of her life, Duras suffered from health problems in the 1980s and 1990s. She underwent a detox program in 1982 that only worsened her health. In 1988 she fell into a coma for five months and was not expected to live. But she recovered and resumed writing, putting her own experiences, now those associated with impending death, front and center as before. Her novel La pluie d'été was published in 1990, and in 1992, partly as a reaction against what she saw as errors on Annaud's film of L'amant, she wrote a new version of the tale, L'amant de la chine du nord (The Lover from Northern China). Her last book, published in English as No More, was a series of diary entries tersely chronicling her physical decay. She continued to write until shortly before her death on March 3, 1996, in Paris.

That event did not dent Duras' popularity as a writer; it was once estimated that more undergraduate theses in American colleges and universities had been written about Duras than about any other figure, and new studies of her work continued to appear at a rapid pace. Even the twilight of her life held fascinating for the public; the 2003 film Cet amour-là dealt with her affair with the young philosophy student and obsessive fan, Yann Lemmée (renamed Yann Andrea by Duras), which began in 1980 and lasted until Duras' death. "I did not deprive my heart of anything," she wrote in a fable that was read (according to the Guardian) at her funeral. "But the sun rises, and sets, and goes back to the place where it is to rise again. I have understood that all is vanity and vanity for vanity's sake. It is food to the wind."

AWARDS

Académie du cinéma Grand Prize, 1983; Goncourt Prize, 1984 for L'amant; Ritz Paris Hemingway Prize, 1985 for L'amant.