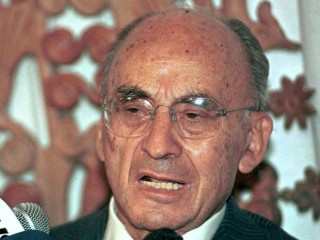

Luis Echeverria biography

Date of birth : 1922-01-17

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Mexico City, Mexico

Nationality : Mexican

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-10-18

Credited as : politician, President of Mexico,

Luis Echeverría Alvarez was the president of Mexico from 1970 to 1976. Although his major interest was foreign affairs, severe economic dislocations diverted his energies to domestic policies. Forced to devalue the Mexican peso twice, he left the presidency under a cloud of despondency.

Luis Echeverría was born on January 17, 1922, in Mexico's Federal District. He received his primary and secondary education in Mèxico City schools and his law degree at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mèxico in 1945. After teaching law for several years Echeverría made his decision to pursue a political career and began working his way through the ranks of Mexico's Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI).

National prominence came to Echeverría in 1957 when he was named chief administrative officer of the PRI's Central Executive Committee and was chosen to give the major nominating speech for the soon to be president Adolfo Lopez Mateos. By 1964, during the presidential administration of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, he was a member of the cabinet and served for six years as secretary of gobernacion. Controversy engulfed him for the first time as he was chosen to negotiate with Mexico City's leftist students threatening to disrupt the opening of the Summer Olympic Games in 1968. His negotiations proved unsuccessful, and political violence resulted in several hundred deaths prior to the opening ceremonies of the Olympiad. In unfounded charges Echeverría took much of the blame for the break down of negotiations. Sensitive to attacks from the left, he sought to mollify his critics by espousing Third World rhetoric for the next two years. The criticism eased off, at least for the time being.

Echeverría's nomination as the presidential candidate of the PRI in 1969 assured his election to his country's highest post the following year, but he conducted a vigorous presidential campaign anyhow. He visited some 900 municipalities, covering 35,000 miles in all 29 Mexican states and the two territories. He relished the opportunity to debate with students and used the opportunity to cultivate the Third World and to criticize the United States.

As president Luis Echeverría traveled abroad more extensively than any previous Mexican president. In addition to visiting a number of Latin American countries, his travels carried him to Japan, the People's Republic of China, England, Belgium, France, and the Soviet Union. The trips were undertaken for the express purpose of opening new avenues of trade. Under his prodding the Mexican government supported the admission of the People's Republic of China to the United Nations. He repeatedly called for Third World countries to maintain their economic independence from the United States. The success and failures of his presidential administration, however, would be measured not on his relationship with the outside world but on his domestic policies.

Luis Echeverría embarked upon a series of policies designed to repudiate the conservative stance adopted by his predecessor, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. To the distress of the conservative Mexican business community, he argued that it was time to slow down the pace of Mexico's industrialization and to renew state initiatives in rural Mexico. In keeping with this policy he supported a new agrarian reform law which encouraged the development of the ejidos, Mexico's rural communal landholdings. He placed major emphasis on extending the rural road system and rural electrification. Perhaps out of conviction, but perhaps to curry favor with the left, in 1971 he released the student prisoners incarcerated during the pre-Olympic demonstrations of 1968. He nationalized the tobacco and telephone industries, and in 1972 he granted diplomatic asylum to Hortensia Allende, widow of the murdered Chilean president Salvador Allende. All of these measures alienated those on the right side of the political spectrum but did little to garner the support of the left.

From 1971 to 1974 President Echeverría learned that his country was not immune from the rural and urban terrorism associated with other Latin American countries. A series of bank robberies were traced to the Movimiento Armado Revolucionario when self-admitted terrorists bragged that their exploits had been undertaken in behalf of a new revolution. Political kidnappings followed in rapid succession. The victims included Julio Hirschfield, director of Mexico's airports; Jaime Castrejon, rector of the University of Guerrero; Terrence Leonhardy, United States consul general in Guadalajara; and Guadalupe Zuno Hernandez, President Echeverría's father-in-law and a former governor of Jalisco. Mexico's image as a progressive and stable republic was beginning to suffer at home and abroad. As events would soon demonstrate, however, President Echeverría's most serious difficulty was not terrorism, but rather an increasingly sluggish Mexican economy.

The Echeverría administration was marked by a huge balance of payment deficits. Tourism, a leading source of Mexico's foreign exchange earning, declined as Echeverría's Third World rhetoric dissuaded many foreign tourists from visiting the country. Spot shortages of electric power and steel prompted a decline in the rate of economic growth. Inflation and high unemployment were rampant. In the summer of 1976 rumors began to circulate that for the first time in 22 years Mexico would have to devalue the peso. President Echeverría tried to convince his fellow countrymen that no devaluation was contemplated, but his repeated assurances did not prevent the flight of hundreds of millions of pesos as wealthy Mexicans exchanged their currency for dollars and invested them in the United States.

The inevitable devaluation came in September 1976, and the peso fell from 12.50 to 20.50 to the dollar, a 60 percent decline. A month later a second devaluation of an additional 40 percent was announced. The second devaluation in a month was psychologically more painful than the first. The president's attempts to blame all of Mexico's economic woes on multi-national corporations and on the United States convinced some, but not many. To be sure, Mexico was a dependent nation and one strongly influenced by the United States, but there was no way to disguise financial mismanagement of major proportions within the Echeverría administration.

Many Mexicans were relieved when Luis Echeverría turned over the presidential office to his successor, Josè Lopez Portillo, in 1976. Those who anticipated that relations with the United States would improve markedly and that the Mexican economy would recover would be disappointed. The trends established during Echeverría's years in office would not be easily reversed.

Echeverría did not disappear from public life after his tenure as president. He became a cacique, a local political boss, and retained his position as president-for-life of the Center for Economic and Social Studies of the Third World. In 1995 he publicly criticized the most recent ex-president of Mexico, Carlos Salinas de Gortari. This broke an important rule in Mexican politics whereby ex-presidents were expected to remain silent on all political matters once they left office. Echeverría's actions caused much controversy and challenged the traditional role of the ex-president.