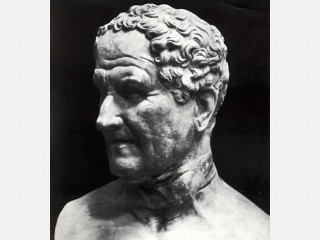

Lucius Cornelius Sulla biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Rome, Italy

Nationality : Roman

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-09-09

Credited as : Roman general and dictator, quaestor under Gaius Marius , defeated the army of Mithridates

0 votes so far

Sidelights

The Roman general and dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 BC) was the first man to use the army to establish a personal autocracy at Rome.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix was generally referred to simply as Sulla Felix, an agnomen that he chose for himself. The appellation “felix” meant lucky, and Sulla was a great believer in his own fortune. He was a Roman of odd character, being both extremely conservative in his political views and simultaneously loose in his social mores. He also possessed a refined, if cruel, sense of humor, and was simultaneously a most cynical and superstitious man. These contradictory traits were well reflected in Sulla’s capricious and unpredictable nature, and he frequently struck unexpectedly at his enemies. He was often described as being half fox and half lion, for Sulla was both brave and cunning to an unusual degree. More than any of these traits, however, Sulla was utterly ruthless. No less an authority than Machiavelli referred to Sulla as a master tyrant in his masterpiece, “The Prince,” proclaiming that the fox in Sulla was the more dangerous part of him. To cross Sulla was to invite disaster. To the end, Sulla’s luck followed him, and unlike many of Rome’s tyrants, he was to die peacefully in bed.

Sulla Felix

Sulla was born in 138 BCE into the prestigious Cornellii family. But though his family lineage was impeccable, his family had long since fallen on hard times. Sulla had no real money and spent his youth idly among the lowest classes of Rome; actors, comedians, musicians, prostitutes, and dancers. He maintained his ties to many of these throughout his life, particularly the actor Metrobious, a “female impersonator” whom Sulla never set aside, even when his own political fortunes were endangered by his colored past.

It is uncertain how Sulla achieved his fortune (Plutarch tells us of two different inheritances; one from his step-mother and another from a scandalously lower class wealthy woman), but we are left to speculate that the greater part of his wealth was from dubious sources. In any event, Sulla had managed to assume the office of quaestor to the rising homo novus Gaius Marius in 107 BCE, just in time to join the new consul in his war against Jurgurtha of Numidia in North Africa.

The Jurgurthine War

The Jurgurthine War had raged unsuccessfully since 112 BCE under the command of Quintus Caecilius Metellus, and Marius, the former chief subordinate to Metellus, had parlayed the opportunity into a command of his own by sending dispatches detailing Metellus’ incompetence back to Rome. Under Marius’ command, the Numidians were defeated in 106 BCE. Jurgurtha fled to King Bocchus of Mauretania for refuge, but Sulla had taken an enormous gamble in approaching Bocchus first. Sulla and Jurgurtha, both under the power of Bocchus, waited for the king to decide which was more in his interest; to betray Jurgurtha to Sulla or Sulla to Jurgurtha. Sulla’s luck held true, however, and he returned safely with Jurgurtha in tow. Sulla’s fame had begun, but the publicity he attracted caused the beginnings of a rift with Marius, who saw his own glory diminished by the attention granted Sulla—even more so when a great gilded statue of Sulla on horseback was donated to the Roman people (and placed in the Forum) by King Bocchus. Sulla remained tied to Marius, however, and the two may well have enjoyed good relations during this time.

The Barbarian Invasions

In 104 BCE the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones were migrating north of Italy, and it appeared that they might well actually invade Italy. After several legions were crushed by the tribes, Marius was elected consul for an unprecedented five consecutive years. In 101 BCE the Roman legions forced a final battle with the tribes at the Battle of Cercellae. Marius was saddled with the incompetent Quintus Lutatius Catulus Caesar as his coconsul, and in order to prevent the inept consul from destroying his plans, Marius had sent Sulla to “guide” the second consular army in the battle. The strategy proved successful and Catulus and Marius were both granted triumphs for the victory. The true victors were known, however, and Sulla’s star continued to rise.

Political Success

Sulla was elected Praetor Urbanus in 97 BCE, but the victory was sullied by rumors of bribery in his run for office. The following year he was appointed proconsul to Cilicia, where he attended a meeting of the ambassador from Pontus and the Parthian ambassador Orobazus. In a stroke of either genius or luck, Sulla took the seat of honor between the two men, resulting in Orobazus being executed by the Parthian king for being outwitted by the Roman. During this same meeting the superstitious Sulla was told by a Chaldean seer that he would die at the height of his fame and power. He clung to this prophecy for the rest of his life. By 92 BCE, Sulla had driven Tigranes, king of Armenia, from Cappadocia and returned to Rome.

The Social War

The assassination of Marcus Livius Drusus saw the Social War erupt in 91 BCE. The Socii, the Italian provincials, were subject to being called upon to provide armies in defense of Rome, but they were granted few rights in exchange, particularly in the area of taxation. Drusus had campaigned to grant the Italian allies full Roman citizenship, which would have granted them equal rights, including seats on the Senate and votes in Roman public bodies. His death had removed the last hope the Italian provincials had cleaved to for justice from Rome.

The Social war was particularly disturbing to the Optimates faction of the Senate. The Optimates were the conservative faction, old blood families that were suspicious and fearful of any change. As a consequence, they were also fearful of the homo novus Marius, whose six consulships had left the ancient Patrician families greatly weakened on the political stage. Casting about for a suitable Patrician counterweight to Marius, they enlisted Sulla as their champion.

The war’s beginning saw Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo (father of Pompey Magnus) struggling mightily against the Italians. For the first time, Rome’s legions faced armies that were equipped, trained, and led just like her own forces. Marius was again called upon to take command and he proceeded to deal several defeats to the Italians in the north. In the south, however, Sulla firmly established a name for himself through his successes. Most spectacularly, he was awarded the corona graminea, the “Grass Crown,” for personal bravery. The Grass Crown was rarely awarded, as it conferred by popular acclamation of the soldiers of a rescued legion to the commanding legate of the rescuing army. Sulla had finally outshined Marius on the battlefield, and the Optimates intended to take full advantage of it. They encouraged Sulla to run for consul in 88 BCE, and the popular Patrician was duly elected.

The March on Rome

While Rome had struggled to defeat her Roman allies, Mithridates of Pontus had seized the opportunity to invade Rome’s provinces in Asia Minor. The Optimates arranged for the Senate to appoint Sulla as the general to lead Rome’s forces against Mithridates, but Marius, perhaps beginning to suffer from old age, still blazed with ambition. After Sulla sent his legions towards the coast in preparation for their move to the East, Marius had one of his tribunes, Publius Sulpicius Rufus, call a popular assembly and override the Senate’s decision. Marius was appointed the commander by popular acclaim.

Violence erupted in the Forum as the patricians attempted to cause a public murder of the type that had claimed the lives of the Gracchi brothers. Sulpicius, however, had a bodyguard that repelled the attempt. In desperation, Sulla went to Marius and asked that he halt the violence. Marius, however, was unmoved by the plea. As the riots continued, Sulla’s son-in-law was killed and Sulla himself was fled Rome for the safety of his army. He made a personal plea to his soldiers particularly appealing to those he had led during the Social War. When the envoys from Rome came to announce that Marius would lead them against Mithridates, Sulla convinced his men to stone the envoys. With his men firmly on his side, he selected his six most loyal legions and marched on Rome.

No Roman general had ever crossed the pomoerium, the city limits, leading an army. It was such a massive break with tradition that all of Sulla’s commanders but one refused to participate. Sulla countered that the Senate had been rendered powerless and that someone had to restore order to the city and honor to the Conscript Fathers. When Sulla’s forces arrived at the city gates, they were resisted by Marius and his allies, but the street rabble were no match for hardened legionaries. Sulla captured the city and Marius, and those who could, escaped into the countryside.

Sulla began ordering Rome as he liked, declaring Marius and his allies enemies of the state, subject to instant death, reestablishing the Senate as the supreme force (beholden to him, of course), and proclaiming the necessity of his actions before the Senate. He then proceeded to take his army once again to the East against Mithridates.

Marius and his allies were far from defeated, however, and once Sulla was safely away, Marius began to make his move. In 87 BCE he returned to Rome, aided by Lucius Cornelius Cinna. Marius immediately declared Sulla’s reforms invalid, exiled the consul, and then established a frightening set of proscriptions that resulted in the slaughter of Sulla’s supporters and the perceived enemies of Marius and Cinna. One hundred of Sulla’s supporters were killed during the proscriptions, and many of them found their heads displayed on the Rostra in the Forum as a warning to all. In an election that held no surprises, Marius and Cinna were elected coconsuls for the following year. Marius was to hold his long prophesized seventh consulship at long last.

Marius’ seventh consulship was not to last long, however, as he died only a few days after assuming office. Cinna, ordering the slaughter of many of the Marians, was now firmly in control of Rome.

The First Mithridatic War

Sulla landed at Dyrrachium, Greece and determined to begin the liberation of Greece in Athens. Along his march he rallied the support of many of the major Greek cities and then, arriving at Athens, he laid siege to the ancient city. Sulla’s attack was typically ruthless, and he even cut down the sacred groves of Greece to supply his siege works. When money became short, he took it from the Greek temples. The siege was long and arduous, and Sulla was frequently insulted by the Athenian tyrant Aristion and his followers, who made unflattering about Sulla’s face, his private life (of which scandal provided many targets), and his wife. As the city began to starve, the Optimate refugees from Rome arrived at Sulla’s camp.

Eventually spies within the walls informed Sulla that one of the walls was unguarded. Sappers were sent and the wall collapsed. A bloodbath ensued, as Sulla allowed his men to take revenge upon the Athenians for all the taunts that had been sent his way. Eventually the pleas of Greek allies and Roman Senators, appalled at the destruction, convinced Sulla to pull his forces back. With Greece essentially back in control, Sulla moved to engage the army of Mithridates at Chaeronea.

Battle of Chaeronea

Chaeronea was Sulla’s masterstroke as a commander. Outnumbered more than three to one, he initially occupied a hill and began to entrench his army. He then moved his army forward to occupy the ruined city of Parapotamii, feigning a retreat as the enemy army closed on him. His men moved back behind entrenched palisades, where the artillery was emplaced. The Pontic army attempted to flank the Roman right wing, but was repelled. Meanwhile, the Pontic chariots charged the Roman center, collapsing onto the palisades. Behind the chariots marched the phalanxes, but the unwieldy formations became stuck upon the palisades as well, and were decimated by continuous fire from the Roman artillery.

With his army in severe danger, the Pontic commander Archelaus hurled his right wing at the Roman left, but Sulla had anticipated this move and moved his reserve to stabilize his left wing. Archelaus flung his remaining troops towards the Roman left wing in desperation, and Sulla, racing back to his right wing, ordered it to charge. The unbalanced Pontic army was rolled up along its left flank, resulting in its nearly total annihilation. Sulla’s use of battlefield entrenchments represented an innovation that had never been seen before. Roman armies had entrenched their camps before, but never prepped the battlefield in such a manner as Sulla had done. It was arguably Sulla’s finest moment.

Orochomenos

The consul Cinna had not been idle in Rome. Secure in his power, he had the Senate send Lucius Valerius Flaccus with an army to relieve Sulla of the eastern command. As the two armies camped nearby one another, Sulla sowed dissension in Flaccus’ army. Watching his army desert before his eyes, Flaccus moved his army north to continue the fight there. Sulla continued to prepare for the new Pontic army, once again commanded by Archelaus.

Outnumbered nearly four to one, Sulla again carefully selected the site of the battle: Orchomenos. Located near a large lake, Sulla began to dig entrenchments and dykes. When the Pontic army arrived, it camped next to the lake, across from the Roman army. Before Archelaus realized what had happened, he was virtually trapped in a web of entrenchments and dykes. Desperate attempts to escape followed, but the tightly packed armies had little room to maneuver. In such terrain, the agile and heavily armored legions excelled, and they cut the Pontic army to shreds. Sulla now accepted a hasty peace with Mithridates, eager to return to Rome to deal with the Marians.

Dictator of Rome

In 82 BCE returned to Italy and again rallied his supporters. He again defeated superior forces in several quick battles, with crucial assistance from Marcus Licinius Crassus and the young Pompey. By 81 BCE, Sulla was once more firmly ensconced in power. This time, he planned to stay. He had himself declared dictator, an office that had traditionally had a time limit of six months. Instead he was appointed indefinitely, and with total control over Rome, he began a reign of terror that made the proscriptions of Cinna and Marius pale in comparison. Every one of Sulla’s opponents was proscribed or outlawed, resulting in more than 1,500 senators and equestrians being executed. Children of the outlawed were banned from all future political office, and the property of the proscribed passed to the state—which meant to Sulla and his supporters. By the end, even those not actually opposed to Sulla were being targeted, solely to obtain their wealth. It was during this time that Crassus began his practice of buying up cheap lands the state had taken from the victims of Sulla’s reign.

Julius Caesar, nephew of Gaius Marius and Cinna’s son-in-law, was also forced to flee the city. He was on the proscription lists, but so many of Caesar’s relatives and their friends interceded on his behalf that Sulla reluctantly agreed to spare his life. Upon meeting Caesar, however, Sulla is said to have commented on the danger he posed to them all, saying, “In this Caesar there are many a Marius.”

Reform and Retirement

Sulla, Patrician to the core, now enacted a series of reforms that effectively stripped the plebians of almost any power of any significance. The tribunes were politically neutered, the Senate doubled in size, and the popular assemblies’ powers to pass laws were curtailed by requiring the Senate’s approval for any action. He even expanded the Pomerium, which had not moved since the Republic had been established.

Sulla’s reforms were intended to turn back the clock to the time before the Gracchi, to when the Patricians had wielded virtually all power in Rome. Now convinced that he had repaired the Republic, Sulla did the unthinkable: he resigned the dictatorship after only two years. He stood for one more consulship, and was duly elected in 80 BCE. After serving his second consulship, he virtually vanished from public sight. Hidden away from the public view, Sulla invited his old companion Metrobius to rejoin him, along with actors, dancers, and all of his childhood crowd. After declaring Metrobius his lifelong lover, Sulla died in 78 BCE, surrounded by such an image of licentiousness that even his staunchest allies were left all but speechless.