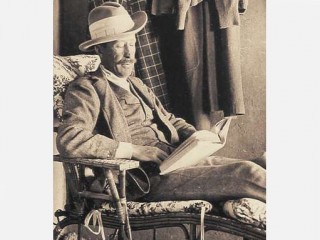

Lord Carnarvon biography

Date of birth : 1866-06-26

Date of death : 1923-04-05

Birthplace : Hampshire, England

Nationality : British

Category : Arhitecture and Engineering

Last modified : 2010-08-25

Credited as : Archaeologist and egyptologist, Pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb, "King Tut"

20 votes so far

Early career

George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert was born at the family home, Highclere Castle, in Hampshire, England, on June 26, 1866. He was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, succeeding to the "Carnarvon" title in 1890. On June 26, 1895 Lord Carnarvon married Almina Victoria Maria Alexandra Wombwell, daughter of Marie Boyer, the wife of Frederick Charles Wombwell, but her real father was possibly Alfred de Rothschild, the unmarried member of the prominent Rothschild banking family of England who made Lady Carnarvon his heiress.

Exceedingly wealthy, Lord Carnarvon was at first best-known as an owner of racehorses and as a reckless driver of early automobiles, suffering, in 1901, a serious motoring accident in Germany which left him significantly disabled.

In 1902, Lord Carnarvon established Highclere Stud to breed thoroughbred racehorses. In 1905, he was appointed one of the Stewards at the new Newbury Racecourse. His family has maintained the connection ever since. His grandson, Henry George Reginald Molyneux Herbert, 7th Earl of Carnarvon, was Racing Manager to Queen Elizabeth II from 1969, and one of Her Majesty's closest friends.

To maintain his health, which seriously suffered after the automobile accident, Lord Carnarvon started to spend more time in the mild climate of Egypt. He visited for the first time in 1903, and after that frequently wintered there. He found the life in Egypt dull, and engaged in collecting local artifacts as a hobby. He soon became fascinated with Egyptology and started to pursue it more enthusiastically.

Egyptologist

Lord Carnarvon moved to the Winter Palace in Luxor to be able to oversee his team of archaeologists excavating in the area of Sheikh Abd el-Qurna. He built a big cage, protected by nets from mosquitoes and dust, which served as the shelter for him and his wife, and from which he could monitor the progress of the diggings. His wife would occasionally accompany him, "dressed for a garden party rather than the desert, with charming patent-leather, high-heeled shoes and a good deal of jewelry flashing in the sunlight" (Dunn). After months of excavations, the expedition ended up in failure. This however did not discourage Carnarvon. He just realized that he needed somebody who would have expertise to find the right location for digging. This led him to meet Howard Carter.

In 1907, with Lord Carnarvon’s money, Carter started to dig in the West Bank of Luxor (ancient Thebes). He first discovered the decorated tomb of Tetiky, an eighteenth Dynasty mayor of Thebes, and then a tomb with two wooden tablets, containing the precepts of Ptahhotep, instructions for moral guidance. In the next several years, Carnarvon and Carter unearthed a series of important finds, among others several private tombs dating from the end of the Middle Kingdom to the beginning of the New Kingdom, and the “lost” temples of Queen Hatshepsut and Ramesses IV.

In 1914 Carnarvon and Carter found their first royal tomb, the burial of Amenophis I (1514-9l3 B.C.E.), ancestor of Tutankhamun, and his mother Ahmose-Nofretiri. After that they turned, in 1915, to the Valley of the Kings. Although it has been thought that most of the sites in the Valley have been exhausted, Carnarvon and Carter believed otherwise. They started to work on the tomb of Amenhotep III, the grandfather of King Tutankhamun, and found numerous smaller artifacts.

During World War I, both Carter and Carnarvon were entrenched in diplomatic work and the excavations were abandoned. They continued with diggings after the war, but with failing results. By 1921, Carnarvon had lost all hope of finding anything valuable in the Valley of the Kings. In 1922, burdened by the lack of finances, he called Carter to his estate in England to tell him that he would cut financing the further excavations. Carter however somehow managed to persuade Carnarvon to provide money for one more expedition.

It was on February 17, 1923 that they together opened the tomb of boy-Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1332-1223 B.C.E.) of the eighteenth Dynasty, exposing artifacts unsurpassed in the history of archaeology. The tomb was completely intact, piled to the ceiling with treasures. The discovery made Carter and Carnarvon world famous over night, but Carnarvon did not live to enjoy that fame.

Two months later, Carnarvon died suddenly, giving popular credence to the story of the "Curse of Tutankhamun," the "Mummy's Curse." His death is most probably explained by blood poisoning (progressing to pneumonia) after accidentally shaving a mosquito bite infected with erysipelas. Rumors spread that at the time he died, the lights in Cairo (where he died in a hospital) went out and plunged the people into darkness. Reportedly, at the same time, back at his home, his pet dog gave out a great howl and died. His colleague and employee, Howard Carter, the man most responsible for revealing the tomb of the young king, lived safely for another sixteen years.

Carnarvon's tomb, appropriately for an archaeologist, is located within an ancient hill fort overlooking his family seat at Beacon Hill, Burghclere, England.

Legacy

The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb was an immediate sensation, ensuring Lord Carnarvon enduring fame. News and reports about the discovery evoked public interest for Egyptology, and the museums that housed some Egyptian artifacts filled with visitors. The temporary exhibition Treasures of Tutankhamun, held by the British Museum in 1972, was the most successful in British history, attracting 1,694,117 visitors. The Egyptian design found in the tomb became inspiration for the fashion designers, especially those in line with Art Deco. The Egyptian motifs became central for the lines of clothes, jewelry, and furniture.

Howard Carter, financed by Lord Carnarvon's wife, spent almost ten additional years supervising the removal of artifacts from the Tutankhamun’s tomb (3,500 in all). Many of these were displayed in British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

After the sudden death of Lord Carnarvon, people spread the rumors of the curse of the king Tutankhamun. The legend of the curse, or the “Curse of the Mummy” as it was called, was exploited in numerous movies and books.