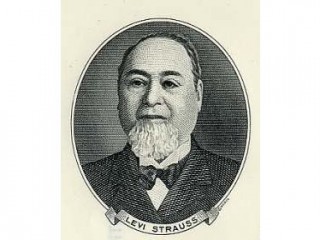

Levi Strauss biography

Date of birth : 1829-02-16

Date of death : 1902-09-26

Birthplace : Buttenheim, Bavaria, German Confederation

Nationality : German

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-10-14

Credited as : manufacturer, blue jeans, Levi Strauss & Co.

Levi Strauss made and sold blue jeans in San Francisco, California, during and after the gold rush. His pants were so popular that Strauss' first name became a household word.

Levi Strauss' father Hirsch Strauss, a dry goods peddler, had four children, Jacob, Jonas, Lippman (later called Louis) and Maila (later called Mary), with his first wife, who died in 1822. Hirsch later married Rebecca Haas, with whom he had two children, Vogela (later called Fanny) and Loeb (later called Levi). Levi, the youngest of the family, was born on February 16, 1829 in the Bavarian village of Buttenheim.

Life in Buttenheim was not easy for Jewish people. They were allowed to live in only one small part of the town. The number of Jewish marriages was restricted, and Jews had to pay special taxes on their homes and businesses. Jews had been attacked and killed in nearby cities. Anti-Semitism drove many Jewish families to immigrate to the United States.

Hirsch Strauss was sick with tuberculosis, a serious lung disease, and could not travel. After he died in 1845, Jonas and Louis journeyed to America and began their own dry goods business. In June 1847, Rebecca, Maila, Vogela, and 18-year-old Levi obtained exit visas and passports. The family traveled to a German port and crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a crowded ship. The uncomfortable voyage lasted many weeks.

The new arrivals joined Jonas and Louis in New York City, where many Jewish immigrants lived. Fanny married David Stern and moved to St. Louis, Missouri, and later to San Francisco, California. Mary married William Sahlein, an uncle. By 1848, Jonas and Louis, who had been working as peddlers, opened a dry goods store in New York City. Levi Strauss began his life in America as a peddler. At the age of 19, he moved to Kentucky, still a frontier area, to sell his goods.

After gold was discovered in California in 1848, many people flocked there to make their fortunes, both by mining and by selling goods to the miners. The 24-year-old Strauss, having recently become an American citizen, joined David and Fanny Stern there in 1853, having endured a long, rough voyage with as many wares as he could carry.

Many legends exist about Levi Strauss, his arrival in San Francisco, and how he sold his first pair of pants. One story stated that, when the ship carrying Strauss approached the shore, men rowed to the vessel and quickly bought almost everything Strauss had brought with him. They paid in gold dust. All that remained was some canvas, a type of strong cloth used for making tents. When a miner heard that all he had left was "tenting," the man said that Strauss should have brought pants to sell, because they didn't last very long at the "diggin's." Strauss took the roll of canvas to a tailor who sewed a pair of pants for the miner. The fellow bragged about how strong those pants of "Levi's" were and that, supposedly, is how Strauss began making the work pants that bore his name.

In San Francisco, Strauss lived with his sister and brother-in-law. Strauss and Stern set up their first store near the wharves on Sacramento Street, where they sold dry goods sent to them by the Strauss brothers in New York and clothing sewn in San Francisco. Because the arrival of goods by sea was so unpredictable, Strauss also bought goods whenever he got the chance, at auctions held on just-arrived ships. He also traveled to many places in northern California, selling goods to miners.

Soon after Strauss had arrived in San Francisco, the Jewish residents of the city began collecting money to build a synagogue. Strauss and Stern donated money to the cause and became members of Temple Emanu-El, a congregation that still exists today. Strauss and another Bavarian Jew, Louis Sloss, donated a real gold medal to the temple each year, to be awarded to the child with the best grades in the Sabbath school.

As the business grew and expanded, Strauss and Stern moved Levi Strauss and Co. several times, finally settling on Battery Street. The wholesale company sold clothing, dry goods, linens, boots, and shoes. Many items were imported from Europe. The company manufactured some of its wares. Some of the firm's most popular items were denim work pants. The company distributed the fabric to seamstresses, who sewed the "waist high overalls" in their homes.

Besides making and selling goods, Levi Strauss and Co. bought real estate, including the Oriental Hotel, located in the center of the city. On October 21, 1868 a strong earthquake struck San Francisco. Strauss' new headquarters was still standing, but badly damaged. He and Stern began planning another building on Battery Street.

By 1870, Strauss was a millionaire and had earned a considerable reputation as a businessman and a philanthropist in San Francisco. He was a member of the Eureka Benevolent Society, a Jewish charitable organization that helped orphans, widows and the needy. With help from Temple Emanu-El, the society raised money to create a Jewish cemetery. Strauss also contributed to the Pacific Hebrew Orphan Asylum and Home and the Hebrew Board of Relief. In 1869, Strauss became a member of the California Immigrant Union, founded to promote California products and to encourage immigration from Europe and the East Coast. In 1897, Strauss established 28 scholarships at the University of California and donated money to the California School for the Deaf.

Strauss enjoyed the cultural events of the city, such as theaters, concerts and social and literary clubs. He also liked giving elegant dinner parties for his friends in private dining rooms at the Saint Francis Hotel. Strauss had the reputation of being fair, honest and unpretentious. He wanted his employees to call him "Levi," rather than "Mr. Strauss." Although he never married or had children, he remained close to his siblings and their children.

One tale recalls Alkali Ike, a miner, and how he constantly tore his pants pockets by stuffing them with ore. To solve the problem, Jacob Davis, a Jewish tailor from Latvia, who then lived in Nevada and regularly bought cloth from Levi Strauss and Co., reinforced the pockets with copper rivets. Davis wanted to patent his invention, but lacked the money needed to do so. He wrote a poorly-spelled letter to Strauss on July 2, 1872, explaining his predicament, as quoted in Everyone Wears His Name: A Biography of Levi Strauss. "The secratt of them Pents is the Rivits that I put in those Pockets and I found the demand so large that I cannot make them up fast enough. My nabors are getting yealouse of these success and unless I secure it by Patent Papers it will soon become a general thing. Everybody will make them up and thare will be no money in it. Therefore Gentlemen, I wish to make you a Proposition that you should take out the Latters Patent in my name as I am the inventor of it." In August 1872, Strauss and Davis applied for a patent, which was granted on May 20, 1873. Davis came to work for Strauss, overseeing the firm's first West Coast manufacturing facility.

David Stern died on January 2, 1874, at the age of 51. His sons Jacob, Louis, and Sigmund all went to work for Levi Strauss and Co. In addition to his business, Strauss owned quite a bit of real estate in downtown San Francisco. He also served on the boards of many firms, such as the San Francisco Gas Co. In 1875, he bought the Mission and Pacific Woolen Mills, using much of the fabric for his "blanket-lined" pants and coats. In 1886, the leather patch showing two horses trying to pull apart a pair of pants was added to the waist overalls. In 1890, the same year the patent expired on the riveted pants, the company listed those pants in its catalog as number 501, a name that stuck. Strauss incorporated Levi Strauss and Co. in 1890, keeping 55 percent of the shares for himself and dividing the rest amongst the seven Stern children.

In 1869, the transcontinental railroad was finally completed, but price fixing by the railroad companies made it very expensive to ship goods by train. In 1891, Strauss and other business owners in San Francisco attempted to create a new railroad line from San Francisco to Salt Lake City, Utah. The plan failed.

Once again, Strauss tried to encourage the development of an alternate rail line. He contributed $25,000 to a scheme devised by Claus Spreckels, the sugar magnate. Other leading business owners also supported the plan to construct the San Francisco and San Joaquin Valley Railroad. Spreckles, the major stockholder, sold his share to new managers, who charged the high rates of the other railroads. Strauss finally gave up on the railroad business.

Although his nephews were running the business by 1890, Strauss continued to go to his office daily, attend meetings, and remain the head of the company. In an interview published on October 12, 1895 in the San Francisco Bulletin, Strauss said, "I do not think large fortunes cause happiness to their owners, for immediately those who possess them become slaves to their wealth. They must devote their lives to caring for their possessions. I don't think money brings friends to its owner. In fact, often the result is quite the contrary."

When he entered his 70s, Strauss developed a heart condition. His doctors recommended more rest. The Strauss family had property in a quiet valley near San Francisco. He rested there as his nephews assumed more responsibility for the business. Strauss also spent time at a resort on the Monterey peninsula called the Del Monte, whose patrons included the most prominent citizens of San Francisco.

The death of Strauss on September 26, 1902 was considered a great loss to San Francisco and its citizens. The San Francisco Board of Trade passed a special resolution marking his death: "The great causes of education and charity have likewise suffered a signal loss in the death of Mr. Strauss, whose splendid endowments to the University of California will be an enduring testimonial of his worth as a liberal, public-minded citizen and whose numberless unostentatious acts of charity in which neither race nor creed were recognized, exemplified his broad and generous love for and sympathy with humanity."