Len Ford biography

Date of birth : 1926-02-18

Date of death : 1972-03-14

Birthplace : Washington D.C., U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-09

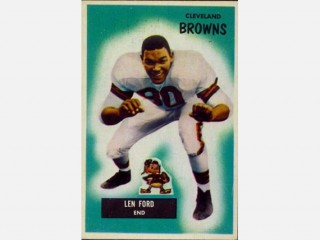

Credited as : Football player/defensive end NFL, played for the Green Bay Packers and Cleveland Browns, inducted into Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1976

0 votes so far

A converted receiver, Len was a monster at 6–5 and 260 pounds. He had the strength to bull through the line for quarterback sacks and the speed to bring down runners before they turned the corner. The outside pass rush was almost unheard of before Len proved it could work. It would not be a stretch to say that he “invented” the quarterback sack. One of the first and best African-American players of the post-WWII era, Len died young—and has gone unappreciated by today’s fan. That’s a shame, for much of what we see in modern NFL defenses didn’t exist until #80 suited up for the Browns.

Leonard Ford was born February 18, 1926 in Washington, D.C. He grew up in the city during the Depression, and like so many other boys, he turned to sports to keep himself occupied. Of course, Len—or “Lennie” as his pals called him—wasn’t remotely like other boys. He was tall, strong and powerful, with soft hands and a mean streak.

Len’s favorite sport was football, and he developed his pass-catching and tackling skills under coach Theodore McIntyre at Armstrong High School. Len was a coach’s dream. He loved to practice as much as he loved to play. McIntyre described him as “a boy who dreamed of football instead of cowboys and indians.”

By the time Len graduated in 1944, he had earned All-City honors in baseball, basketball and football. He had captained Armstrong’s teams in all three sports. Len was remembered as a monstrous hitter in baseball. Had major-league ball been opened to African-Americans back then, it is likely that he would have chosen that path to greatness.

At McIntyre’s suggestion, Len enrolled at Morgan State University in Maryland, where the legendary Eddie Hurt had coached the football teamto several undefeated seasons. Len wore #50 during his one year in Baltimore, starring on both sides of the ball for the Bears. He also played center for the basketball team, which won a league championship.

After a brief stint in the Navy, Len transferred to the University of Michigan in 1945. Head football coach Fritz Crisler was happy to have him. Len left Morgan State for one reason—he had always dreamed of playing in the Rose Bowl, and this was his chance. Although Michigan was a predominantly white team, several African-American players had enjoyed success with the Wolverines, including Julius Franks, a lineman who had earned All-America honors a few years earlier. Bob Mann, a black receiver, would join Len on the team—and later integrated the NFL’s Detroit Lions.

Len wore #87 for Michigan, and at 6–5, he was by far the tallest player on the team. A left end for most of his college career, he cracked the Wolverines’ starting lineup as a junior in 1946. He earned some All-America mentions for his fine play, particularly on defense.

Len’s senior year was something special. He was the fastest “big man” in the Big Ten Conference—and probably in all of college football. He used his strength to move blockers out of his way on defense. As a receiver, his leaping ability and size made him nearly impossible to cover. Heading into the ’46 campaign, several national sports publications named Len a preseason All-American, including Sportfolio, which described him as a “Negro junior from Washington, D.C.—a great defensive wingman who has sufficient pass-catching ability to handle anything Wolverine halfback Bob Chappuis throws his way.”

The Wolverines were known as the “Mad Magicians” for their tricky, four-man backfield formations. As Len’s sernior season unfolded, it became clear that Michigan was one of the great teams of all time. Chappuis led a group that included Bump Elliott, Al Wistert, and Dick Rifenburg, who played right end across from Len on offense. The balhawking seven-man defensive line comprised Len and Ed McNeil at each end, Wistert and Ralph Kohl at tackle, guards Joe Soboleski and Quent Sickels, and center Dan Dworsky. Len was in charge of stopping the sweep, plus occasional pass coverage. In those days, ends did not rush the quarterback —they simply lined up too far away on the outside to be effective.

The Wolverines lived up to their billing and went undefeated. They routed Michigan State (55–0), Stanford (49–13), Pitt (69–0), and beat up on arch rival Ohio State, 21–0. Michigan kept rolling in the Rose Bowl, whipping USC, 49–0, in Len’s last college game. Jack Weisenburger scored three touchdowns for Michigan, Chappuis riddled the Trojans with snappy passes, and Len buried USC ball carriers again and again.

Len wanted very much to play pro ball, but many teams were reluctant to draft African-American players. Not a single NFL club picked Len, despite the fact that he had been an All-American and played well in the annual College All-Star Game in Chicago. The Los Angeles Dons of the two-year-old All American Football Conference had no such qualms. They signed Len to contract for the 1948 season.

Playing for the Dons was an interesting experience for Len. He met plenty of Hollywood celebrities, including Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Don Ameche—each of whom had a small piece of the team. Los Angeles was coming off a season that saw them go 7–7, while drawing 40,000-plus fans a game in the Coliseum. The team's wealthy owner, Ben Lindeheimer, knew you had to spend money to make money. Besides luring Len away from the NFL, he signed rookie Herm Wedemeyer for $12,000—a princely sum in the postwar years.

In 1947, the Dons were the only team to beat the juggernaut Cleveland Browns. In 1948, they set their sights on a division title in the AAFC’s West Division. Coach Jim Phelan installed a new spread offense to maximize the skills of the team’s great star, Glenn Dobbs.

That season, Len played tight end and caught 31 passes for 598 yards and seven touchdowns. He used his enormous hands to make several great leaping, one-handed catches. Len was part of a receiving corps that included Joe Aguirre, Dale Gentry and Wedemeyer. That quartet accounted for 133 receptions in 14 games. Dobbs ended up leading the team in rushing and leading the AAFC in pass completions and punting.

Len also played on the defensive line for the Dons. He was a superb pass rusher, brutalizing the poor backs assigned to block him and using his size and soft hands to pick off one pass. That did not prevent L.A.’s defense from allowing 305 points—not a horrible number, but quite a bit more than the 258 the team scored. Despite this differential, the team finished 7–7 again, beating up on the league's bad teams and going 2–6 against the better ones.

The 1949 season was the AAFC’s last. Contraction had whittled the league down to a single division comprised of seven clubs. Lindeheimer kept opening his wallet, but he was losing the battle of Los Angeles to the NFL’s Rams, who featured sexier players like Bob Waterfield, Norm Van Brocklin, Tom Fears and Crazy Legs Hirsch. The Dons’ owner even lent money to other AAFC teams. But in the end, his team managed a meager four victories and finished in sixth place.

Len led the Dons with 36 catches, broke the 500-yard mark again and also intercepted one pass on defense. He scored only one touchdown. Still, coach Phelan had high praise for one of the team’s lone bright spots that year. “Len can become the greatest all-around end in history,” he said. “He has everything—size, speed, strength and great hands.”

The play everyone remembered from that season came on defense, in a game against the New York Yankees. Spec Sanders, the AAFC’s top rusher, took a handoff and tried to run through the center of the line. Len had no chance of making the tackle, so he crashed into a New York blocker, lifted him in the air and threw him backwards into Sanders, who lay in a bewildered heap near the line of scrimmage.

The AAFC’s misfortune turned out to be a blessing for Len. The Dons had lost to the Browns twice in 1949 by scores of 42–7 and 61–15, so he was delighted to receive an offer from Cleveland, which joined the NFL for the 1950 season. Despite the fact that Len had some great receiving days against his new team, Paul Brown had no thoughts of using him on offense. The Cleveland coach saw Len as a game-changing defensive end, and as usual he was right.

“He was so devastating on defense we knew this was his natural spot,” Browns assistant Blanton Collier once said. “Len was very aggressive and had that touch of meanness in him, that you find in most defensive players.”

Len also practiced as hard as he played, something Brown valued highly in his charges. Len's midweek battles with teammate Abe Gibron were legendary.

Len was so good creating havoc in the backfield and sealing off the corner that Brown believed he could take on two players at the point of attack. This allowed Cleveland to create front four of two defensive ends and tackle, backed by a trio of linebackers—what we know today as the 4–3 defense. For Len, it meant a shorter distance to the passing pocket, as well as a sharper angle. He would make great use of both.

The Browns erased lingering doubts about the quality of the AAFC by going 10–2 in their first NFL season. Both losses came at the hands of the New York Giants, who also finished 10–2. In the divisional playoff, Cleveland choked off New York’s offense, winning 8–3. Bill Willis, Len’s friend and fellow African-American pioneer, saved the season by running down Choo-Choo Roberts on a breakaway and preventing the potential winning touchdown.

Len watched this game from the sideline. Earlier in the year, in a game against the Chicago Cardinals, he took a shot to the face from Pat Harder. It was an ugly injury—Len broke his nose, fractured both cheekbones and lost several teeth. Ironically, he was flagged for unnecessary roughness on the play. Len had taken a swing at Harder and was ejected from the game. Earlier, Len had been penalized for punching Ed Bagley, and he had also cracked a couple of Harder’s teeth that afternoon. The NFL rescinded the $50 fine that came with an ejection when commissioner Bert Bell saw the damage Harder had done.

The injury kept Len out the rest of the year and required plastic surgery to repair. When owner Mickey McBride saw Len in the locker room, he was so upset that he threatened to shut down the Browns if the NFL didn’t do more to punish offenders like Harder.

For his part, Len downplayed the incident. He had already gained a reputation as a player who often crossed the line, and he had no problem with the bone-shattering shot from Harder. “Harder’s not to blame,” he said. “I am—for not getting out of the way of his elbow.”

In the days before facemasks, this type of hit was usually a career-ender. But a week after the playoff win against New York, Len amazed Cleveland fans when he suited up for the NFL Championship against his old crosstown rivals, the Rams. Len had a special cage made to protect his face. Coach Brown promised he would use him only in an emergency.

Despite having dropped 20 pounds after being on a liquid diet for six weeks, Len entered the game in the second quarter and played the rest of the way like an unchained elephant. He dropped L.A. runners for big losses three different times and disrupted the Rams’ passing game in the final minutes of a dramatic 30–28 comeback victory.

Len played the whole year in 1951, bookending with left defensive end George Young as the Cleveland defense allowed only 18 touchdowns—8 rushing and 10 passing touchdowns, both of which were league-leading figures. Len opened a lot of eyes around the NFL. If a blocker tried to cut him at the legs, he hurdled him. If Len was caught moving the wrong way on a play, he could spin himself back into it. And no one pursued quarterbacks with more gusto. Long before the quarterback sack was a stat—or even a word, for that matter—Len was the league’s sack master.

The Browns went 11–1 in ’51 and met the Rams again in the NFL Championship. This time L.A. came out on top. With the game tied 17–17 in the fourth quarter, Norm Van Brocklin hit Tom Fears with a 73-yard TD pass for the win.

The Browns relied on Len more than ever in 1952, though they failed to find their stride and won only eight games. He and Willis were unstoppable, killing drives with bone-crunching tackles. Both were All Pros and selected to play in the season-ending Pro Bowl. And, as it turned out, eight victories was enough to win the East. For the third straight year, the Browns played for the NFL Championship, this time against the Lions.

Detroit had a huge advantage against the Browns—Cleveland’s two best receivers, Mac Speedie and Dub Jones, were injured and unable to play. Compounding the Browns’ problems were several boneheaded plays. The Lions won, 17–7.

The Browns came back in 1953 to win their first 11 games and sail to another division title. Quarterback Otto Graham was terrific, and new stars like Ray Renfro stepped up when given the opportunity. New owner Dave Jones liked what he saw, esepcially along the defensive line, where Len welcomed Don Colo to the mix. Along with Willis—in his last NFL season—they made Cleveland’s defense almost impenetrable. Unfortunately, the one time they needed a stop—at the end of the NFL Championship game against the Lions—the Browns were victimized by the arm of Bobby Layne and the toe of Doak Walker. They lost for the third year in a row, 17–16.

The Browns needed Len more than ever in 1954, and he delivered. They lost longtime stars Willis and Marion Motley to retirement, and then dropped two of their first three games—including a shocker to the lowly Pittsburgh Steelers, 55–27. Graham did what he could with the offense, but it was Cleveland’s defense—which allowed a mere nine touchdowns in its final nine games—that resurrected the club and delivered yet another conference championship.

Len was at the height of his powers. He believed there was no one in the NFL who could block him one-on-one, and a peek at the scouting reports from that era confirms that opponents agreed with him. Opposing teams basically ran plays away from him.

In his fifth year playing in a 4–3 defensive set, Len had all but perfected the art of outside pass-rushing, creating many of the moves that are still seen on NFL fields today. His quick hands and leaping ability—vestiges of his days as a receiver—enabled him to clog passing lanes and pick off passes. He was particularly adept at causing and collecting fumbles. Len was behind a slew of turnovers for the Browns in ’54—none more important than the two passes he picked off against the Lions in the NFL title game. He returned one 45 yards, which was a record for championship games at that time. The Browns annihilated the Lions, 56–10.

Teams now regularly ignored certain plays when they faced Cleveland because of Len. Most long pass plays were non-options because of how quickly he could penetrate the pocket. “There were things you couldn’t do out of certain formations or Lennie was going to break through and make the play,” Bob St. Clair of the San Francisco 49ers recalls.

Age, however, was the great equalizer. The 1955 season marked Len’s last as an All-Pro and Pro Bowl pick. He had another dominant campaign, as did the Browns, despite the advancing years of their stars. Curly Morrison was the top ground gainer, Darrell Brewster their top receiver. Graham, who had planned to retire, was cajoled into coming back for another year. Coach Brown shuffled players in and out of games as needed. The result was a 9–2–1 record and yet another conference championship.

In the title game against the Rams, Len and linemates Carlton Massey and Colo kept the pressure on Van Brocklin, forcing him into several poor passes and six interceptions. It was a great day for the defense, as Cleveland prevailed 38–14.

The Browns’ run of East titles finally came to an end in 1956. Graham’s retirement, plus injuries to his two replacements, doomed Cleveland to the first losing season in team history at 5–7. Len was still a force on the defensive line, but at 30, he was starting to slip, and young guns Rosey Grier and Gino Marchetti replaced him on most All-Pro lists. Marchetti more than Grier pushed the defensive end position along. Later, Deacon Jones turned it into a sack festival.

Len’s final season in Cleveland was 1957. The focus of the defense had started to shift to the linebacking corps, led by Galen Fiss, Walt Michaels and Vince Costello. The Browns returned to the top of the standings with a 9–2–1 record. The Lions, still smarting from their 1954 title loss, repaid the favor by beating Cleveland in the NFL Championship, 59–14.

Len was traded by the Browns after the season as part of a rebuilding program. The Cleveland staff felt young Paul Wiggin was ready to step in, so the team dealt Len to the punchless Green Bay Packers for a draft pick. He played one season as a sub and then called it a career. It was a difficult year. The Packers won only one game; Len had never played for a losing team before.

In 11 seasons as a pro, Len was an first-team All-Pro five times and played in four Pro Bowls. He recovered 20 fumbles (an NFL record at the time) and picked off six passes. He walked away with two championship rings and a reputation for having redefined the position of defensive end. During Len's eight seasons in Cleveland, the Browns gave up the fewest points in the NFL six times and the second-fewest twice.

As quiet and modest off the field as he was terrifying on it, Len insisted that winning always came down to making sacrifices. “The result you get from any endeavor depends upon the effort you put into it,” he liked to say.

Len put that philosophy to work in his post-football life, which was tragically short. He worked as the Assistant Recreation Director for the City of Detroit, passing on his wisdom and life lessons to inner-city kids in America’s toughest town. His wife, Geraldine, was an attorney who became a judge in Detroit.

Len passed away from heart disease on March 14, 1972, after being hospitalized for a month. He was just 46.

Four years later, Len was voted into the Hall of Fame—the first defensive player from those great Cleveland teams to be enshrined, and the first D.C. native to earn the honor. He was one of three inductees, with Ray Flaherty and Jim Taylor being the others. Len was remembered as a player who literally gave everything he had on every play and performed his best when a championship was on the line. Few players—in or out of Canton—can truly claim this distinction.

Lou Groza, who played the line with Len and later became a full-time kicker, admired the gusto with which his teammate approached the game. “Lenny used to delight in running over guys,” he recalled.

Len’s coach, Paul Brown, may have summed up his value as a defensive player best with three words uttered to a room full of reporters just a few weeks after he joined the team: “He splatters ’em.”

At Canton, Len’s daughter Deborah gave the acceptance speech. “Daddy,” she said when she was done, “you’ve made it!”