Laurent-Desire Kabila biography

Date of birth : 1939-11-27

Date of death : 2001-01-18

Birthplace : Baudouinville, Belgian Congo

Nationality : Congolese

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-09-10

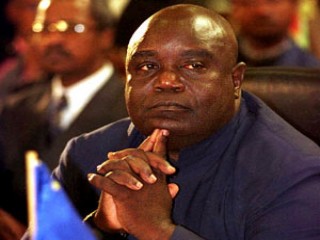

Credited as : politician, President of Zaire, Democratic Republic of Congo

Laurent-Désiré Kabila is the president of the central African nation called Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire).

Few figures emerge on the world stage as suddenly as Laurent Kabila did in the last months of 1996. It is a measure of the speed with which he made his appearance that there were literally hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles about him in the United States and Britain during the first half of 1997-but almost no pieces whatever for the five years preceding that time. In October of 1996, he entered the limelight as the leader of Zairian forces rising up against the corrupted regime of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. Less than six months later, troops under his command took control of the capital, Kinshasa, and Kabila became the leader of the country, now renamed Democratic Republic of Congo. With its location at the center of Africa, its physical size (as large as Western Europe), and its troubled past, Congo occupies a strategic position in Africa, and suddenly leaders all over the world were asking "Who is Laurent Kabila?" The answer to that question lies beneath layers of mystery, and indeed analysts are far from agreement as to who he is or what he intends for his country's future.

Kabila was born in 1939, in Shaba Province, part of the region then called Belgian Congo. This was the same land described memorably by Joseph Conrad in his novel Heart of Darkness (1902), a vast stretch of jungles, rivers, and mountains nearly one million square miles in area. Belgian rule in the Congo became legendary for its cruelty, but by the time Kabila reached maturity, there were few colonial empires left in Africa. One legacy of the Belgians was the French language; therefore when it came time for Kabila to receive a university education, he went to France and studied political philosophy.

By the time Kabila returned home, the Congo was in a state of turmoil. It had gained its independence from Belgium in 1960, but that was far from the end of the new nation's troubles; in fact, those had only really begun. By now the old struggle of the European colonial empires was an artifact of history, and the new battle over Africa was the Cold War conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States. The Soviets supported Marxist Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, and so did Kabila, who became a pro-Lumumba member of the North Katanga Assembly, a provincial legislature. The United States, on the other hand, supported Lumumba's chief opposition, an army officer named Joseph Dsir Mobutu.

A bloody civil war ensued, and in 1961, Mobutu allegedly had Lumumba killed. Kabila fled to the Ruzizi lowlands, and tried to wage war against the government from there, but was defeated. In 1963, he formed the People's Revolutionary Party, and set up operations on Lake Tanganyika, at the country's eastern edge. Two years later, he was joined by one of the twentieth century's most prominent revolutionary leaders, a man who in 1959 had helped Fidel Castro take power in Cuba, Ernesto "Che" Guevara. Guevara kept a diary during the six months of 1965 that he spent in Africa, released in English as Bolivian Diary [of] Ernesto "Che" Guevara (1968). In the volume, he complained bitterly about Kabila's lack of commitment, and his penchant for spending time away from the front, "in the best hotels, issuing communiques and drinking Scotch in the company of beautiful women." Though admitting that Kabila was young (26 years old) and therefore capable of change, Guevara wrote, "for now, I am willing to express serious doubts, which will only be published many years hence, that he will be able to overcome his defects."

By the end of 1965, it became clear that Mobutu was about to win the war, so Guevara left in disgust. In 1966, Mobutu took power and declared himself head of the nation, which he renamed Zaire in 1971. He also gave himself a new name, the abbreviated form of which was Mobutu Sese Seko, which in full meant something like "the rooster who leaves no hens alone." Zaire came under Mobutu's domination, and he made himself one of the world's richest men while keeping his people in extreme poverty.

Kabila's life during the three decades between the mid-1960s and the mid-1990s are somewhat of a mystery. In the early 1970s, his People's Revolutionary Party established a "liberated zone" in Kivu Province, and spent the next 20 years in periodic fighting with the government. Kabila himself went into exile in neighboring Tanzania in 1977, and from there he continued to lead guerrilla attacks against the increasingly repressive and corrupt Mobutu regime. While Mobutu stole both from his people and the Western nations who gave him financial aid, Kabila engaged in some questionable dealings himself, not the least of which was the kidnapping of hostages-including some Americans. In addition, Congo expert Gerard Prunier told ABC News, "[Kabila] and his supporters killed elephants, quite ecologically, and did mining. Then they smuggled the ivory and diamonds and gold through Burundi."

Burundi was one of three small countries on Zaire's eastern border, and events in the other two nations-Uganda and Rwanda-led to a dramatic change in fortunes for Kabila, who all but disappeared from view by 1988. Tensions began to mount between Rwanda's two main ethnic groups, the Hutus and the Tutsis, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and because the Hutus were in power, Tutsi refugees were spread throughout Uganda and Zaire. Kabila moved to Uganda in the early 1990s, and became associated with a group of Tutsis who helped a rebel leader named Yoweri Museveni take power in that country. When civil war broke out in Rwanda in 1994 following massacres of Tutsis by Hutus, two things happened: Museveni's Tutsi associate Paul Kagame became the vice president and de facto leader of Rwanda, while fleeing Hutus flooded Zaire.

As the Rwandan civil war spread over into Zaire, Mobutu attempted to conduct a campaign of ethnic cleansing against his country's Tutsi minority. The latter, supported by Kagame in their homeland, began an uprising, and as they took town after town, they were joined by Zairians eager to throw off Mobutu's rule. By October of 1996, Kabila emerged as the leader of the group, which he called the "Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire."

Journalists described Kabila, a large man with a bald head, as jovial in manner, though this was certainly no cause for relief, since Uganda's notorious Idi Amin had been described the same way 25 years before. And it did not help that he refused to speak much about his past: "When he is asked about himself or his family, " the New York Times reported on April 1, 1997, "Mr. Kabila-a stout man with an easy laugh-invariably changes the subject with a deep chuckle and a wave of the hand." Other journalists, most notably Philip Gourevich of the New Yorker, were apt to give Kabila the benefit of a doubt and so too were representatives of the United Nations, the United States, and the continent's most noted political leader, Nelson Mandela of South Africa.

Mobutu was out of power by May of 1997-he died in September of that year, ironically in the same week as Princess Diana and Mother Teresa-and Kabila was the new president. Kabila assumed leadership of the country, which he renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo, on May 29, 1997, and the months that followed did not appear to confirm the high hopes many had expressed for the nation's future. Kabila's troops engaged alternately in lawless robbery, or in strict enforcement of repressive social codes, such as a ban on miniskirts. His foreign minister justified clampdowns on demonstrations, claiming they were unnecessary. Kabila stalled United Nations teams attempting to investigate allegations regarding massacres of Hutus, and he had the chief opposition leader, Etienne Tshisekedi, jailed briefly.

The people of Congo had pinned their hopes on Kabila, who used the same middle name as Mobutu once had: Dsir, which means "the one hoped for" in French. But by September 18, 1997, the Christian Science Monitor was reporting that hopes for genuine change were ebbing. People even claimed nostalgia for the Mobutu era, since as one Zairian said, the soldiers under Mobutu could be counted on to spare people who bribed them-unlike the loose cannons of the Kabila regime.

Yet there was still hope to be found in the person of Kabila's backer and mentor, Museveni. The latter has enacted democratic and pro-market reforms in Uganda, exerts enormous sway throughout Africa, and has urged a pro-Western stance on the part of his allies. This may be a pragmatic response to a situation in which there is little choice, as the New Republic observed in a June 16, 1997, assessment of the new Kabila regime entitled "The End and the Beginning": with the Cold War over, Africa is no longer a staging ground for superpower conflict, and African leaders cannot count on Western dollars to prop up their regimes. Observers who wish for genuine positive change in the country formerly known as Zaire, a place rich in natural resources and poor in its history of freedom, can only hope that the West will maintain a policy of constructive engagement with Kabila and the other leaders of the Democratic Republic of Congo.