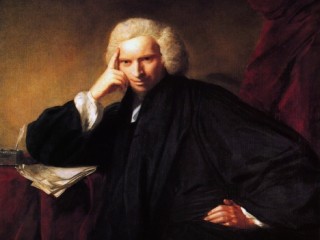

Laurence Sterne biography

Date of birth : 1913-11-24

Date of death : 1768-03-18

Birthplace : Clonmel, Ireland

Nationality : British

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-09-14

Credited as : fiction novelist, Gentleman, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy,

The British novelist Laurence Sterne produced only two works of fiction, but he ranks as one of the major novelists of the 18th century because of his experiments with the structure and organization of the novel.

The English novel came of age in the 18th century. Daniel Defoe had contributed realistic detail in the 1720s; Samuel Richardson had showed the dramatic intensity inherent in the epistolary novel; Henry Fielding had combined the satirical portrayal of contemporary manners with elaborate and carefully worked-out plots. Laurence Sterne, however, published the single most idiosyncratic novel of the century, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (1760-1767). The apparent plotlessness of Tristram Shandy, the endless digressions and wordplay, and the use of the narrator's psychological consciousness as the governing structure in the novel make Sterne unique among the early masters of the English novel and suggest a tie to the stream-of-consciousness novelists who appeared later.

Sterne was born in Clonmel, Ireland, on Nov. 24, 1713, the son of an English army officer, Roger Sterne, and an Irish mother, Agnes. After spending his early years moving about with his father's regiment, he attended school in Yorkshire from 1723 to 1731. Sterne received a bachelor of arts degree from Jesus College, Cambridge, took orders in 1737, and in 1738 became the vicar at Sutton-in-the-Forest, near York, the first of several benefices in and near York that he held. His marriage to Elizabeth Lumley in 1741 proved unhappy.

In 1743 Sterne published his first verses, "The Unknown World, Verses Occasioned by Hearing a Pass-Bell," in the Gentleman's Magazine. But neither his verses nor his second work, A Political Romance (1759), later called The History of a Good Warm Watch, a work that had grown out of a quarrel with fellow clerics, had prepared the English reading audience for the first two volumes of Tristram Shandy, which were published early in 1760.

The enormous popularity of Sterne's unusual novel quickly made him a celebrity and gave him social access to the great houses of London and Bath. In 1762 the consumption that plagued his entire life forced him to abandon London society and to seek better health in France. During the last winter before his death, Sterne readied his A Sentimental Journey for the press and carried on a curious platonic affair with Mrs. Eliza Draper, the wife of a Bombay official in the East India Company. Sterne's letters to Mrs. Draper were collected in the Journal to Eliza.

Sterne's irascibility and bawdy humor were well known to his congregations and to the English public. His local reputation around York was based, at least in part, on his eccentric dress and habits, his mordant wit, and his fund of indecorous anecdotes. It is said that he preached sermons on brotherly love with unusual rancor and ill temper. He died in London on March 18, 1768.

With the London publication of volumes 1 and 2 of Tristram Shandy on Jan. 1, 1760, Sterne was launched as a successful author. There were baffled readers, bored readers, and indignant readers, but as Sterne observed, even those who condemned the book bought it. Samuel Richardson found the work "too gross to be inflaming," and Horace Mann noted: "I don't understand it. It was probably the intention that nobody should." Within a few months, Sterne had become a literary lion in London. He admitted that he intended to publish additional volumes as part of the novel "as long as I live, 'tis, in fact, my hobbyhorse." Sterne published volumes 3-6 in 1761; volumes 7 and 8 appeared in 1765; and in 1767, not long before Sterne's death, volume 9 appeared. Although Dr. Samuel Johnson observed of Sterne's novel that "nothing odd will do long," it has survived both neglect and the attacks of critics, and it continues to please, puzzle, and attract more readers than any other 18th-century English novel.

The apparently chaotic structure and puzzling chronology of Tristram Shandy are easily clarified. For example, Tristram is born on Nov. 5, 1718; attends Jesus College, Cambridge; and begins his latest volume on or about Aug. 12, 1766. Parson Yorick dies in 1748. Sterne's intention, of course, was to experiment with the straight-forward chronological development of plot that had previously characterized English fiction. By dramatically scrambling chronological and psychological durations, he emphasized the dual nature of time, something to which an individual responds both by reason and by emotion. Despite the immediate confusions of the book, with its blank pages, marbled pages, squiggles, erudite references, footnotes, and puzzling time sequence (Tristram is not born until a third of the way through the work), the novel has an artistic structure of its own, a coherence that resides primarily in the character of Tristram, who holds together all of the elements of the novel, shifting his attention from character to character and from idea to idea. Influenced by the work of John Locke, Sterne concentrated less on the passage of time as the clock measures it than on mental time, in which events can move more or less quickly than clock time. Because the consciousness of the narrator is the unifying factor in the novel, Tristram Shandy can be considered a completed work.

The characters in Tristram Shandy deserve special note because of their idiosyncracies. Tristram himself seems so scatterbrained that he cannot organize his thoughts. He is quickly and easily diverted from whatever topic he is discussing to frequent digressions. While Mrs. Shandy, Obadiah, Susanna, and Dr. Slop never escape from actuality, "My Father" and Uncle Toby ride special "hobbyhorses." "My Father" believes that life should be presided over by theory, but he never troubles to see that life is so ordered. Indeed, life seems less important to him than the idea and contemplation of it. He propounds his theory of noses (the longer the better), of names (Tristram is the worst of all possible names), and of education (the Tristapedia) in the course of the novel. Although Uncle Toby is literally too sentimental to harm a fly, he is so obsessed with warfare, military campaigns, and battle strategy that he can regret that the Peace of Utrecht has ended war in Europe.

Tristram Shandy is bawdy, satiric, humorous, sentimental, filled with Sterne's extensive learning and crammed with footnotes and foreign languages. Much of the novel is made up of talk about Sterne's writing chores and his rhetorical relation to the reader. The book stands as a rich catalog of the possibilities of misunderstanding and confusion inherent in language.

Parson Yorick, who dies in Tristram Shandy, was habitually identified with Sterne, an identification that he himself promoted in 1760 and again in 1766 by publishing his sermons under the title The Sermons of Mr. Yorick. This identification is also apparent in the brief A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy (1768), a reworking of volume 7 of Tristram Shandy. In both works Parson Yorick is a whimsical, good-hearted, slightly daffy character. The Journey, employing typical Sternean techniques, follows Yorick on a tour through France and Italy punctuated with misadventures, sexual ploys, and the usual fill of digressions and abrupt shifts in topic and tone. Sterne's Sermons, from which he earned a considerable income, shows the development of a moral theory that is more imaginative than his orthodox religion and more complex as a philosophy.

Sterne's fiction exhibits his ability to give immediacy to a dialogue; to handle dramatic techniques with great skill; to capture idiom with delightful mimicry; to quote frequently—if not always accurately—from the Bible and William Shakespeare and other English authors; and to present his ideas with a witty indecision that charms the reader even as it goads his patience.

The small number of letters that form Sterne's correspondence exhibit his playfulness with language and provide an intensely personal view of him. Unfortunately, many of Sterne's letters were burned by John Botham or mutilated by Sterne's daughter, Lydia, before their first publication in 1775.