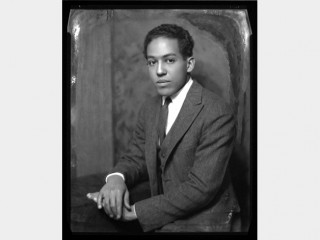

Langston Hughes biography

Date of birth : 1902-02-01

Date of death : 1967-05-22

Birthplace : Joplin, Missouri, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-07-13

Credited as : Novelist and playwright, writer of short stories and columnist, also an innovator of jazz poetry

44 votes so far

United States – died May 22, 1967 in New York City, New York, United States) was an American poet, novelist, playwright, short story writer, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best-known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the Harlem Renaissance saying that "Harlem was in vogue."

Langston Hughes is "possibly the most influential black American writer of the twentieth century," declared Dictionary of Literary Biography (DLB) contributor R. Baxter Miller. Though known primarily as a poet, Hughes also worked as a journalist, playwright, and lecturer. He was the first black American to support himself entirely by writing and giving lectures. John Mark Eberhart, writing for the Knight-Ridder/Tribune News Service in 2001, stated: "Here was a true son of the Midwest who moved on to fame as part of the Harlem Renaissance but never forgot the peculiar fusion of joy and hardship in his upbringing: familial love vs. racism, black dignity vs. white derision, righteous anger vs. unrighteous hate and, most of all, writing of all kinds as a weapon against the world's defects. Poems, novels, plays, short stories, political essays, autobiography: These torrents fell from Hughes' pen from his teen years till his death at 65 in 1967."

Hughes was born February 1, 1902 in Joplin, Missouri, to James and Carrie Hughes. Though usually regarded as black, Hughes stated in his first autobiography, The Big Sea: "You see, unfortunately, I am not black. There are lots of different kinds of blood in our family. But here in the United States, the word 'Negro' is used to mean anyone who has any Negro blood at all in his veins. In Africa, the word is more pure. It means all Negro, therefore black. " Both of Hughes's paternal great-grandfathers, one of whom was a slave trader, were white; on his mother's side of the family, one of his great-grandfathers was white and had been a slave owner. Other family members also had unusual histories. Commenting on Arnold Rampersad's The Life of Langston Hughes, David Nicholson noted in the Washington Post Book World that Hughes's great-uncle was "John Mercer Langston, 'the first black American to hold office . . . by popular vote,' lawyer, U.S. minister to Haiti, acting president of Howard University, and congressman from Virginia."

Hughes's parents struggled constantly to make more of themselves than was usually allowed of black people at the time: James studied law by correspondence course but was not allowed to sit for the bar exam, and Carrie sought to earn a living outside the field of domestic labor. The struggle was detrimental to their marriage. James moved to Mexico to escape the racism of the United States. He sent for his family, "but no sooner had my mother, my grandmother, and I got to Mexico City," Hughes recounted, "than there was a big earthquake, and people ran . . . and the big National Opera House they were building sank down into the ground, and tarantulas came out of the walls--and my mother said she wanted to go back home at once to Kansas. . . . So we went. And that was the last I saw of my father until I was seventeen."

Shortly after arriving in Kansas, Hughes went to live with his maternal grandmother while his mother traveled to find work. Hughes's grandmother, who was partly of Indian and French ancestry, had been the first black woman to attend Oberlin College. Before marrying Hughes's grandfather, who had helped maintain part of the Underground Railroad, she had been the wife of Lewis Sheridan Leary, one of a few black men who fought alongside the abolitionist John Brown; her first husband was killed during Brown's raid on the munitions at Harper's Ferry shortly before the Civil War. In a review of Rampersad's book for the Observer, Christopher Hitchens noted that Hughes, as an infant, had slept under Leary's "bullet-riddled shawl." Hughes recalled in The Big Sea the stories told by his grandmother, "long, beautiful stories about people who wanted to make the Negroes free, and how her father had apprenticed to him many slaves in Fayetteville, North Carolina, before the War, so that they could work out their freedom under him as stone masons. And once they had worked out their purchase, he would see that they reached the North, where there was no slavery." As described by Miller, Hughes was also taken by his grandmother "to hear speeches by (black educator and author) Booker T. Washington, and in 1910 to Osawatomie, where as the last surviving widow of John Brown's raid, she sat on the speaker's platform with (former President) Theodore Roosevelt." When Hughes was twelve, his grandmother died, and he remained with a couple of her friends for about a year until his mother sent for him.

At that time, Hughes moved to Lincoln, Illinois to be with his mother, her new husband, Homer Clark, and their young son. Hughes completed grammar school in Lincoln, graduating in 1916 after having been selected as the class poet. He recalled, "there was no one in our class who looked like a poet, or had ever written a poem. . . . In America most white people think, of course, that all Negroes can sing and dance, and have a sense of rhythm. So my classmates, knowing that a poem had to have rhythm, elected me unanimously--thinking, no doubt, that I had some, being a Negro." Prior to his responsibility as class poet, Hughes hadn't considered writing poetry. After graduating from grammar school, Hughes moved with his family to Cleveland, Ohio, where he enrolled in Central High School and was elected editor of the yearbook his senior year.

In 1920, Hughes's father requested that he come to Mexico and discuss his life plans with him. Relations between Hughes and his father were strained, as Hughes's friend Gwendolyn Brooks observed in a review of The Life of Langston Hughes for the New York Times Book Review: "His father he remembered only too sharply: 'I hated my father.' And the father, Hughes said, 'hated Negroes. I think he hated himself, too, for being a Negro. He disliked all of his family because they were Negroes.'" However, thinking that this might be his only chance to get a college education since his mother had made clear her belief that he could now support her, Hughes went to see his father. Upon crossing the Mississippi River on the train ride to Mexico, Hughes wrote his first major poem, a short verse titled "The Negro Speaks of Rivers." Miller commented that "through the images of water and pyramid, the verse suggests the endurance of human spirituality from the time of ancient Egypt to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The muddy Mississippi made Hughes think of the roles in human history played by the Congo, the Niger, and the Nile, down whose water the early slaves were once sold. And he thought of Abraham Lincoln, who was moved to end slavery after he took a raft trip down the Mississippi. The draft he first wrote on the back of an envelope in fifteen minutes has become Hughes's most anthologized poem." In Mexico, Hughes taught English to children of the wealthy. At the same time, his story "Mexican Games" was published in Brownie's Book, the children's periodical of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" was first published in 1921 in The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP.

In September, 1921, Hughes enrolled in Columbia University, but "because of the bigotry and indifference that he found there, he withdrew after successfully completing his freshman year," according to DLB contributor Catherine Daniels Hurst. Then, in 1923, Hughes signed on to the S.S. Malone as a mess boy on a voyage to Africa. Ironically, the Africans that Hughes met regarded him as white, since some of his ancestors were white. Hughes worked on other ships in return for passage to several European countries; he also found jobs in France, Spain, and Italy before returning to the United States in 1924. His first published poetry collections were The Weary Blues, printed in 1926, and Fine Clothes to the Jew, published the next year.

Hughes became one of the leading figures of the "Harlem Renaissance" of the 1920's, during which other black writers such as Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, and Zora Neal Hurston also attained prominence. However, Hughes came under attack from members of the intellectual black community, who feared that his poetry depicted an unattractive view of black life. Hughes stated that "Fine Clothes to the Jew was well received by the literary magazines and the white press, but the Negro critics did not like it at all. The Pittsburgh Courier ran a big headline across the top of the page, LANGSTON HUGHES' BOOK OF POEMS TRASH. The headline in the New York Amsterdam News was LANGSTON HUGHES--THE SEWER DWELLER. The Chicago Whip characterized me as 'the poet low-rate of Harlem.' Others called the book a disgrace to the race, a return to the dialect tradition, and a parading of all our racial defects before the public."

Commenting upon such criticism, Hughes wrote: "I felt that the masses of our people had as much in their lives to put into books as did those more fortunate ones who had been born with some means and the ability to work up to a master's degree at a Northern college. Anyway, I didn't know the upper class Negroes well enough to write much about them. I knew only the people I had grown up with, and they weren't people whose shoes were always shined, who had been to Harvard, or who had heard of Bach. But they seemed to me good people, too." Indeed, other critics have cited the form and content of Hughes's depictions of common people as the source of his poetry's appeal. "The success of these poems owes much to the clever and apt device of taking folk-song forms and idioms as the mold into which the life of the plain people is descriptively poured," stated Locke in an article for the Saturday Review of Literature. Noting Hughes's concern with common people and use of folk forms in his poetry, Negro American Literature Forum contributor Edward E. Waldron asserted that "while Langston Hughes certainly did not limit himself to any one form or subject, his concern with the common man--the source of the blues--makes his use of the blues form especially 'right.'"

In 1926, Hughes enrolled in Lincoln University near Philadelphia, and received his A.B. in 1929. It was at this time that Hughes first described his "mission as an artist, . . . to write about the black man in America with truth and honesty," Hurst asserted. While in school, Hughes wrote his first novel, Not Without Laughter, for which he earned four hundred dollars. During his study at Lincoln, the author had enjoyed the patronage of Charlotte Mason, a wealthy and elderly white woman living in New York. However, Hughes suffered "a series of misunderstandings with the kind lady who had been my patron," as he described in his second autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey. "She wanted me to be more African than Harlem--primitive in the simple, intuitive and noble sense of the word. I couldn't be, having grown up in Kansas City, Chicago and Cleveland." Mason was also the patron of Zora Neal Hurston, with whom Hughes later collaborated and had a falling-out.

Hughes needed to find work, but couldn't get a regular job writing since editors did not hire blacks at that time. "Almost all the young white writers I'd known in New York in the 'twenties had gotten good jobs with publishers or magazines as a result of their creative work," the author asserted. "White friends of mine in Manhattan, whose first novels had received reviews nowhere nearly as good as my own, had been called to Hollywood, or were doing scripts for the radio. Poets whose poetry sold hardly at all had been offered jobs on smart New York magazines. But they were white. I was colored."

While visiting Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, Hughes was advised by the college's president Mary McLeod Bethune, whom he called "that most distinguished of Negro women," to give readings of his poems on a tour of the South. His tour lasted from 1931 to 1932, during which time he sold many copies of The Weary Blues, which were available for one dollar each. For those who couldn't afford one dollar, Hughes prepared a smaller booklet which sold for twenty-five cents.

From 1932 to 1933, Hughes toured the Soviet Union and Central Asia. In Moscow, Hughes first turned his attention to writing fiction after reading a book of short stories written by the British author D. H. Lawrence. "It had never occurred to me to try to write short stories before, other than the enforced compositions of college English," Hughes related. "But in wondering, I began to think about some of the people in my own life, and some of the tales I heard from others, that affected me in the same hair-raising manner as did the characters and situations in D. H. Lawrence's two stories. . . . I sent my first three stories from Russia to an agent in New York, and by the time I got back to America he had sold all three. . . . And once started, I wrote almost nothing but short stories."

Hughes began writing plays in the mid-1930s. "Hughes's plays are one with his poetry--deceptively simple in theme, structure, and plot," Hurst wrote. "They use the idiom of the ordinary black people of the urban North (usually Harlem). Designed to appeal not to pretentious middle-class blacks but to the common people that he identified with and loved."

In 1937, Hughes worked as a correspondent for the Baltimore Afro-American, covering the actions of American blacks fighting in the Spanish civil war; the Cleveland Call Post and the Boston Globe also bought some of his articles. Upon returning to the United States in January, 1938, Hughes established the Harlem Suitcase Theater in Manhattan. Tickets were sold for thirty-five cents each and performances were scheduled on the weekends for the convenience of working people. The next year, Hughes established the New Negro Theater in Los Angeles, and in 1941 he founded the Skyloft Players in Chicago.

In 1943 Hughes began working for the Chicago Defender, writing a weekly column that featured a character named Jesse B. Semple, nicknamed "Simple." Simple is a poor resident of Harlem, a kind of comic no-good, a stereotype Hughes turned to advantage. He tells his stories to Boyd, the foil in the stories who is a writer much like Hughes, in return for a drink. Writing in Newsweek, Saul Maloff described Simple as "a hilarious black Socrates of the neighborhood saloons." In another essay for DLB, Miller noted that Hughes had read Miguel de Cervantes' novel Don Quixote, and that "later he would credit Cervantes with influencing his conception of his character Jesse B. Simple." The "Simple" columns were later collected in five books.

Hughes settled in Harlem in 1947 and maintained residence there until his death in 1967. He continued to write throughout that time, producing fiction, poetry, drama, nonfiction, and juvenile works, and he also edited anthologies of poems, essays, and short stories. His works specifically written for children include the poetry collections The Dream Keeper and Other Poems and Black Misery. Black Misery is a series of one-liners describing the difficulties faced by children, especially black children. Hughes also wrote nonfiction works for children, which "presented historical information about the origins of Afro-American people and provided informal explanations of their arts and of jazz, as a musical form," stated Barbara T. Rollock in Writers for Children. Rollock observed that Hughes "also wrote or collaborated on biographies of blacks whose accomplishments were exemplary, or whose lives could serve as sources of motivation for the young." In 1965, Hughes lectured in Europe under the auspices of the U.S. Information Agency. The following year, he was decorated by Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia.

During the racially turbulent latter years of his life, Hughes continued to hope for a world in which people could live together sanely and with understanding, unlike younger and more militant writers who sometimes took extreme political positions. Reviewing The Panther and the Lash: Poems of Our Times in Poetry, Laurence Lieberman recognized that Hughes's "sensibility (had) kept pace with the times," but criticized his lack of a personal political stance. "Regrettably, in different poems, he is fatally prone to sympathize with starkly antithetical politics of race," Lieberman commented. "A reader can appreciate his catholicity, his tolerance of all the rival--and mutually hostile--views of his outspoken compatriots, from Martin Luther King to Stokely Carmichael, but we are tempted to ask, what are Hughes' politics? And if he has none, why not? The age demands intellectual commitment from its spokesmen. A poetry whose chief claim on our attention is moral, rather than aesthetic, must take sides politically."

Nevertheless, Langston Hughes's position in the American literary scene is secure. David Littlejohn in his Black on White: a Critical Survey of Writing by American Negroes wrote that Hughes is "the one sure Negro classic, more certain of permanence than even (James) Baldwin or (Ralph) Ellison or (Richard) Wright. . . . By molding his verse always on the sounds of Negro talk, the rhythms of Negro music, by retaining his own keen honesty and directness, his poetic sense and ironic intelligence, he maintained through four decades a readable newness distinctly his own."

The author of Hughes' biography in St. James Guide to Young Adult Writers wrote of Hughes: "He was driven by a desire to 'explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America,' and he was a pioneer in combining the rhythms of street speech, the blues, and the language of the black community with the formal patterns and structural conventions of the traditional English poetry he had mastered. Hughes is not generally regarded as a poet whose work is specifically addressed to young adult readers and listeners, but in his attempt to address the concerns of African-Americans while exploring the universal questions of human existence, he has excluded no part of an audience with a degree of literacy and a grasp of the fundamentals of language. Almost all of his poetry is accessible and engaging because Hughes was influenced by such popular American poets as Sandburg, Vachel Lindsay, and Edgar Lee Masters who were interested in reaching a wide audience rather than a literary elite, but certain aspects of Hughes's poetry have a particular appeal for younger readers.

"The spirit of optimism and his faith in human beings pervades most of his work, but it is tempered by realistic assessment of the effects of racial hatred. There is a sense of a justifiable grievance in Hughes' writing, but it almost never shades into bitterness, so that the positive elements don't seem shallow or spurious. Instead, they reflect a determination to transcend the destructive and soul-crushing tendencies of poems written in rage and frustration."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born February 1, 1902, in Joplin, MO; died May 22, 1967, of congestive heart failure in New York, NY; son of James Nathaniel (a businessman, lawyer, and rancher) and Carrie Mercer (a teacher; maiden name, Langston) Hughes. Education: Attended Columbia University, 1921-22; Lincoln University, A.B., 1929. Memberships: Authors Guild, Dramatists Guild, American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers, PEN, National Institute of Arts and Letters, Omega Psi Phi.

CAREER

Poet, novelist, short story writer, playwright, song lyricist, radio writer, translator, author of juvenile books, and lecturer. In early years worked as assistant cook, launderer, busboy, and at other odd jobs; worked as seaman on voyages to Africa and Europe. Lived at various times in Mexico, France, Italy, Spain, and the Soviet Union. Baltimore Afro-American, Madrid correspondent, 1937; Atlanta University, visiting professor in creative writing, 1947; Laboratory School, University of Chicago, poet in residence, 1949.

WORKS

Writings

POETRY

* The Weary Blues, Knopf (New York, NY), 1926.

* Fine Clothes to the Jew, Knopf (New York, NY), 1927.

* The Negro Mother and Other Dramatic Recitations, Golden Stair Press (New York, NY), 1931.

* Dear Lovely Death, Troutbeck Press, 1931.

* The Dream Keeper and Other Poems, Knopf (New York, NY), 1932.

* Scottsboro Limited: Four Poems and a Play, Golden Stair Press (New York, NY), 1932.

* A New Song, International Workers Order, 1938.

* (With Robert Glenn) Shakespeare in Harlem, 1942.

* Jim Crow's Last Stand, Negro Publication Society of America, 1943.

* Freedom's Plow, Musette Publishers (New York, NY), 1943.

* Lament for Dark Peoples and Other Poems, Holland, 1944.

* Fields of Wonder, Knopf (New York, NY), 1947.

* One-Way Ticket, Knopf (New York, NY), 1949.

* Montage of a Dream Deferred, Holt (New York, NY), 1951.

* Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz, Knopf (New York, NY), 1961.

* The Panther and the Lash: Poems of Our Times, Knopf (New York, NY), 1967.

NOVELS

* Not Without Laughter, Knopf (New York, NY), 1930, reprinted, Macmillan (New York, NY), 1986.

* Tambourines to Glory, John Day, 1958, reprinted, Hill & Wang (New York, NY), 1970.

SHORT STORIES

* The Ways of White Folks, Knopf (New York, NY), 1934, reprinted 1971.

* Simple Speaks His Mind, Simon & Schuster (New York, NY), 1950.

* Laughing to Keep from Crying, Holt (New York, NY), 1952.

* Simple Takes a Wife, Simon & Schuster (New York, NY), 1953.

* Simple Stakes a Claim, Rinehart (New York, NY), 1957.

* Something in Common and Other Stories, Hill & Wang (New York, NY), 1963.

* Simple's Uncle Sam, Hill & Wang (New York, NY), 1965.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

* The Big Sea: An Autobiography, Knopf (New York, NY), 1940 reprinted, Thunder's Mouth, 1986.

* I Wonder as I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey, Rinehart (New York, NY), 1956, reprinted, Thunder's Mouth, 1986.

NONFICTION

* A Negro Looks at Soviet Central Asia, Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the U.S.S.R., 1934.

* (With Roy De Carava) The Sweet Flypaper of Life, Simon & Schuster (New York, NY), 1955, reprinted, Howard University Press (Washington, DC), 1985.

* (With Milton Meltzer) A Pictorial History of the Negro in America, Crown (New York, NY), 1956, 4th edition published as A Pictorial History of Black Americans, 1973.

* Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP, Norton (New York, NY), 1962.

* (With Meltzer) Black Magic: A Pictorial History of the Negro in American Entertainment, Prentice-Hall (Englewood Cliffs, NJ), 1967.

* Black Misery, Paul S. Erickson, 1969.

JUVENILE

* (With Arna Bontemps) Popo and Fifina: Children of Haiti, Macmillan (New York, NY), 1932.

* The First Book of Negroes, F. Watts (New York, NY), 1952.

* The First Book of Rhythms, F. Watts (New York, NY), 1954.

* Famous American Negroes, Dodd (New York, NY), 1954.

* Famous Negro Music Makers, Dodd (New York, NY), 1955.

* The First Book of Jazz, F. Watts (New York, NY), 1955, revised edition, 1976.

* The First Book of the West Indies, F. Watts (New York, NY), 1956 (published in England as The First Book of the Caribbean, E. Ward, 1965.

* Famous Negro Heroes of America, Dodd (New York, NY), 1958.

* The First Book of Africa, F. Watts (New York, NY), 1960, revised edition, 1964.

EDITOR

* Four Lincoln University Poets, Lincoln University, 1930.

* (With Arna Bontemps) The Poetry of the Negro, 1746-1949, Doubleday (New York, NY), 1949, revised edition published as The Poetry of the Negro, 1746-1970, 1970.

* (With Waring Cuney and Bruce M. Wright) Lincoln University Poets, Fine Editions, 1954.

* (With Arna Bontemps) The Book of Negro Folklore, Dodd (New York, NY), 1958, reprinted, 1983.

* An African Treasury: Articles, Essays, Stories, Poems by Black Africans, Crown (New York, NY), 1960.

* Poems from Black Africa, Indiana University Press (Bloomington, IN), 1963.

* New Negro Poets: U.S., foreword by Gwendolyn Brooks, Indiana University Press (Bloomington, IN), 1964.

* The Book of Negro Humor, Dodd (New York, NY), 1966.

* The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers: An Anthology from 1899 to the Present, Little, Brown (Boston, MA), 1967.

TRANSLATOR

* (With Mercer Cook) Jacques Roumain, Masters of Dew, Reynal & Hitchcock (New York, NY), 1947, second edition, Liberty Book Club, 1957.

* (With Frederic Carruthers) Nicolas Guillen, Cuba Libre, Ward Ritchie (Los Angeles, CA), 1948.

* Selected Poems of Gabriela Mistral, Indiana University Press (Bloomington, IN), 1957.

OMNIBUS VOLUMES

* Selected Poems, Knopf (New York, NY), 1959, reprinted, Vintage Books (New York, NY), 1974.

* The Best of Simple, Hill & Wang (New York, NY), 1961.

* Five Plays by Langston Hughes, edited by Webster Smalley, Indiana University Press (Bloomington, IN), 1963.

* The Langston Hughes Reader, Braziller (New York, NY), 1968.

* Don't You Turn Back (poems), edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, Knopf (New York, NY), 1969.

* Good Morning Revolution: The Uncollected Social Protest Writing of Langston Hughes, edited by Faith Berry, Lawrence Hill, 1973.

* (With Arna Bontemps) Arna Bontemps-Langston Hughes Letters: 1925-1967, edited by Charles H. Nichols, Dodd (New York, NY), 1980.

* Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, 1925-1964, Vintage (New York, NY), 2002.

* Also author of numerous plays (most have been produced), including Little Ham, 1935, Mulatto, 1935, Emperor of Haiti, 1936, Troubled Island, 1936, When the Jack Hollers, 1936, Front Porch, 1937, Joy to My Soul, 1937, Soul Gone Home, 1937, Little Eva's End, 1938, Limitations of Life, 1938, The Em-Fuehrer Jones, 1938, Don't You Want to Be Free, 1938, The Organizer, 1939, The Sun Do Move, 1942, For This We Fight, 1943, The Barrier, 1950, The Glory Round His Head, 1953, Simply Heavenly, 1957, Esther, 1957, The Ballad of the Brown King, 1960, Black Nativity, 1961, Gospel Glow, 1962, Jericho-Jim Crow, 1963, Tambourines to Glory, 1963, The Prodigal Son, 1965, Soul Yesterday and Today, Angelo Herndon Jones, Mother and Child, Trouble with the Angels, and Outshines the Sun.

* Also author of screenplay, Way Down South, 1942. Author of libretto for operas, The Barrier, 1950, and Troubled Island. Lyricist for Just Around the Corner, and for Kurt Weill's Street Scene, 1948. Columnist for Chicago Defender and New York Post. Poetry, short stories, criticism, and plays have been included in numerous anthologies. Contributor to periodicals, including Nation, African Forum, Black Drama, Players Magazine, Negro Digest, Black World, Freedomways, Harlem Quarterly, Phylon, Challenge, Negro Quarterly, and Negro Story.

* Some of Hughes's letters, manuscripts, lecture notes, periodical clippings, and pamphlets are included in the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection, Beinecke Library, Yale University. Additional materials are in the Schomburg Collection of the New York Public Library, the library of Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and the Fisk University library.

* Hughes' works are continually in print and being published individually and in various collections. In a monumental project, The University of Missouri Press will bring Hughes' entire works together in an eighteen-volume set. Each volume will contain a detailed chronology and will be edited, with an introduction by, an expert in the particular genre. The poetry collection will include both published and unpublished versions of each of Hughes' poems.