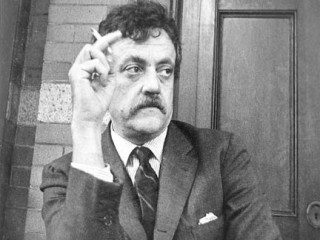

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. biography

Date of birth : 1922-11-11

Date of death : 2007-04-11

Birthplace : Indianapolis, Indiana, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-10-04

Credited as : Novelist, ,

1 votes so far

November 11, 1922, is the date of Kurt Vonnegut's birth, a birthday he considered significant for its coincidence with Armistice Day celebrations noting the end of World War I. From his upbringing in Indianapolis, Indiana, among a culturally prominent family descended from German immigrant Free-Thinkers of the 1850s, the young author-to-be developed attitudes that would see him through the coming century of radical change. Pacifism was one such attitude; another was civic responsibility; a third was the value of large extended families in meeting the needs of nurture for both children and adults. The first test of these attitudes came in the 1930s, when during the Great Depression his father's work as an architect came to an end (for lack of commissions) and his mother's inherited wealth was depleted. These circumstances forced Kurt into the public school system, where, unlike his privately educated older brother and sister, he was able to form close childhood friendships with working-class students, an experience he says meant the world to him. Sent off to college with his father's instruction to "learn something useful," Vonnegut joined what would have been the class of 1944 at Cornell University as a dual major in biology and chemistry with an eye toward becoming a biochemist. Most of his time, however, was spent writing for and eventually becoming a managing editor of the independent student owned daily newspaper, the Cornell Sun.

World War II interrupted Kurt Vonnegut's education, but for awhile it continued in different form. In 1943, he avoided the inevitable draft by enlisting in the United States Army's Advanced Specialist Training Program, which made him a member of the armed services but allowed him to study mechanical engineering at the Carnegie Technical Institute and the University of Tennessee. In 1944, this one-of-a-kind program was canceled when Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower made an immediate request for 50,000 additional men. Prepared as a rear-echelon artillery engineer, Vonnegut was thrown into combat as an advanced infantry scout, and was promptly captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge. Interned as a prisoner of war at Dresden, he was one of the few survivors of that city's firestorm destruction by British and American air forces on the night of February 13, 1945, the event that becomes the unspoken center of Slaughterhouse-Five, named after the underground meatlocker where the author took shelter. Following his repatriation in May of 1945, Kurt Vonnegut married Jane Cox and began graduate study in anthropology at the University of Chicago.

During these immediately postwar years he also worked as a reporter for the City News Bureau, a pool service for Chicago's four daily newspapers. Unable to have his thesis topics accepted and with his first child ready to be born, Vonnegut left Chicago without a degree and began work as a publicist for the General Electric (GE) Research Laboratory in Schenedtady, New York. Here, where his older brother Bernard was a distinguished atmospheric physicist, Kurt drew on his talents as a journalist and student of science in order to promote the exciting new world where, as GE's slogan put it, "Progress Is Our Most Important Product." Yet this brave new world of technology rubbed the humanitarian in Vonnegut the wrong way, and soon he was writing dystopian satires of a bleakly comic future in which humankind's relentless desire to tinker with things makes life immensely worse. When enough of these short stories had been accepted by Collier's magazine so that he could bank a year's salary, Kurt Vonnegut quit GE. Moving to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in 1950, he thenceforth survived as a full time fiction writer, taking only the occasional odd job to tide things over when sales to publishers were slow.

Throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s, Vonnegut published 44 such stories in Collier's, The Saturday Evening Post, and other family-oriented magazines, sending material to the lower-paying science fiction markets only after mainstream journals had rejected it. Consistently denying that he is or ever was a science fiction writer, the author instead used science as one of many elements in common middle class American life of the times. When his most representative stories were collected in 1968 as Welcome to the Monkey House, it became apparent that Vonnegut was as interested in high school bandmasters and small town tradesman as he was in rocket scientists and inventors of cyberspace; indeed, in such stories as "Epicac" and "Unready to Wear," the latter behave like the former, with the most familiar of human weaknesses overriding the brainiest of intellectual concerns.

Kurt Vonnegut's novelist career began as a sidelight to his short story work, low sales, and weak critical notice for these books, making them far less remunerative than placing stories in such high-paying venues as Cosmopolitan and the Post. It was only when television replaced the family weeklies as prime entertainment that he had to make novels, essays, lectures, and book reviews his primary source of income, and until 1969, these earnings were no better than any of Vonnegut's humdrum middle class characters could expect. When Slaughterhouse-Five became a bestseller, however, all this earlier work was available for reprinting, allowing Vonnegut's new publisher (Seymour Lawrence, who had an independent line with Dell Publishing) to mine this valuable resource and further extend this long-overlooked new writer's fame.

It is in his novels that Vonnegut makes his mark as a radical restylist of both culture and language. Player Piano (1952) rewrites General Electric's view of the future in pessimistic yet hilarious terms, in which a revolution against technology takes a similar form to that of the ill-fated Ghost Dance movement among Plains Indians at the nineteenth century's end (one of the author's interests as an anthropology scholar). The Sirens of Titan (1959) is a satire of space opera, its genius coming from the narrative's use of perspective--for example, the greatest monuments of human endeavor, such as the Great Wall of China and the Palace of the League of Nations, are shown to be nothing more than banal messages to a flying saucer pilot stranded on a moon of Saturn, whiling away the time as his own extraterrestrial culture works its determinations on earthy events. Mother Night (1961) inverts the form of a spy-thriller to indict all nations for their cruel manipulations of individual integrity, while Cat's Cradle (1963) forecasts the world's end not as a bang but as a grimly humorous practical joke played upon those who would be creators. With God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965) Vonnegut projects his bleakest view of life, centered as the novel is on money and how even the most philanthropical attempts to do good with it do great harm.

By 1965, Kurt Vonnegut was out of money, and to replace his lost short story income and supplement his meager earnings from novels, he began writing feature journalism in earnest (collected in 1974 as Wampeter and Foma & Granfalloons) and speaking at university literature festivals, climaxing with a two-year appointment as a fiction instructor at the University of Iowa. Here, in the company of the famous Writers Workshop, he felt free to experiment, the result being (in an age renowned for its cultural experimentation) his first bestseller, Slaughterhouse-Five. Ostensibly the story of Billy Pilgrim, an American P.O.W. (Prisoner of War) survivor of the Dresden firebombing, the novel in fact fragments six decades of experience so that past, present, and future can appear all at once. Using the fictive excuse of "time travel" as practiced by the same outer space aliens who played havoc with human events in The Sirens of Titan, Vonnegut in fact recasts perception in multidimensional forms, his narrative skipping in various directions so that no consecutive accrual of information can build--instead, the reader's comprehension is held in suspension until the very end, when the totality of understanding coincides with the reality of this actual author finishing his book at a recognizable point in time (the day in June, 1968 when news of Robert Kennedy's death is broadcast to the world). Slaughterhouse-Five is thus less about the Dresden firebombing than it is a replication of the author's struggle to write about this unspeakable event and the reader's attempt to comprehend it.

The 1970s and 1980s saw Vonnegut persevere as a now famous author. His novels become less metaphorical and more given to direct spokesmanship, with protagonists more likely to be leaders than followers. Breakfast of Champions (1973) grants fame to a similarly unknown writer, Kilgore Trout, with the result that the mind of a reader (Dwayne Hoover) is undone. Slapstick (1976) envisions a new American society developed by a United States president who replaces government machinery with the structure of extended families. Jailbird (1979) tests economic idealism of the 1930s in the harsher climate of post-Watergate America, while Deadeye Dick (1982) reexamines the consequences of a lost childhood and the deterioration of the arts into aestheticism. Critics at the time noted an apparent decline in his work, attributable to the author's change in circumstance: whereas he had for the first two decades of his career written in welcome obscurity, his sudden fame as a spokesperson for countercultural notions of the late 1960s proved vexing, especially as Vonnegut himself felt that his beliefs were firmly rooted in American egalitarianism preceding the 1960s by several generations. Galápagos (1985) reverses the self-conscious trend by using the author's understanding of both biology and anthropology to propose an interesting reverse evolution of human intelligence into less threatening forms. Bluebeard (1997) and Hocus Pocus (1990) confirm this readjustment by celebrating protagonists like the abstract expressionist Rabo Karabekian and the Vietnam veteran instructor Gene Hartke who articulate America's artistic and socioeconomic heritage from a position of quiet anonymity.

That Kurt Vonnegut remained a great innovator in both subject matter and style is evident from his later, better developed essay collections, Palm Sunday (1981) and Fates Worse Than Death (1991), and his most radically inventive work so far, Timequake (1997), which salvages parts of an unsuccessful fictive work and combines them with discursive commentary to become a compellingly effective autobiography of a novel. His model in both novel writing and spokesmanship remains Mark Twain, whose vernacular style remains Vonnegut's own test of authenticity. As he says in Palm Sunday, "I myself find that I trust my own writing most, and others seem to trust it most, too, when I sound like a person from Indianapolis, which is what I am."

Vonnegut continued to write and participate in interviews until his death on April 11, 2007, from brain injuries as a result of a fall several weeks earlier at his home in New York. Two other collections of short stories and essays, Armageddon in Retrospect and Look at the Birdie, were published posthumously in 2008 and 2009, respectively.