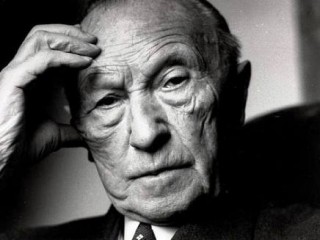

Konrad Adenauer biography

Date of birth : 1876-01-05

Date of death : 1967-04-19

Birthplace : Cologne, Germany

Nationality : German

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-09-07

Credited as : statesman, chancellor of the Federal Rapublic of Germany,

The German statesman Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967) was chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) from 1949 to 1963.

Konrad Adenauer was born in 1876 in Cologne, and his career was always closely connected with this city in the Rhineland region of Germany. Although his father was a Prussian soldier and minor civil servant, Adenauer shared the common ambivalence of the Rhinelanders to the Prussian-dominated German Empire.

Even as a young man, Adenauer was reserved, somewhat ascetic, and hardworking rather than brilliant in his studies. Severe thrift and the support of friends enabled him to study law at the universities of Freiburg im Breisgau, Munich, and Bonn. Adenauer then worked for an influential Cologne lawyer, who was the head of the local German Center party organization. (The German Center party had been formed by Catholics to protect their interests against the Protestant-dominated government.) Through hard work, ambition, and party contacts, Adenauer became an assistant to the lord mayor of Cologne in 1906. He soon became the equivalent of deputy mayor and finally lord mayor in 1917. During these years Adenauer had married and had three children.

Adenauer faced many crises in his 16-year tenure as mayor. He successfully dampened the fires of revolution that swept Cologne at the end of World War I. After flirting with movements for a Rhenish state separate from Prussia (and possibly even Germany), Adenauer became noted as a strong representative of Rhineland interests against the central government in Berlin. As a leading member of the Center party, he was chairman of the upper house of the Prussian state legislature from 1920 to 1933.

Adenauer's life was not without dark sides. His first wife died during World War I, and he suffered severe facial injuries in an automobile accident which left him a victim of insomnia. In 1933 Adenauer, an opponent of Nazism, was driven from office by the new regime of Hitler. He was persecuted sporadically, and in 1934 and 1944 he was arrested by the Gestapo. On the latter occasion his second wife was mistreated and later died. Adenauer narrowly escaped being sent to the concentration camp at Buchenwald. But for the most part he spent the years from 1933 to the end of World War II quietly in his villa on the Rhine, cultivating his garden and avoiding politics.

When American troops seized Cologne, Adenauer was offered his old post of lord mayor. Although he was almost 70, his reputation as a good administrator untainted by Nazism gave him a political edge. Conflicts with the British occupation authorities late in 1945, however, led to Adenauer's dismissal. He then threw himself into reviving German Center party activities. He concurred with other former leaders of the party that it must broaden its base to include all faiths that supported democratic institutions. To achieve this end, he was a cofounder of a new political party—the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). With the backing of the Catholic Church and influential Cologne businessmen, Adenauer rapidly advanced from head of the local CDU (1945) to chairman of the party for the British Zone (1946) and finally for all of West Germany (1949). In 1948 he was elected president of the Parliamentary Council, a body that drew up the political foundations for a new German republic composed of the British, American, and French occupation zones.

When the first federal parliamentary elections in 1949 resulted in a victory for the CDU, Adenauer outmaneuvered his many adversaries to become the first chancellor. The decisive single vote which gave him a majority was his own. He was reelected in 1953, 1957, and 1961.

As chancellor, Adenauer was often criticized for behaving more autocratically than the Basic Law (constitution) of 1949 intended. He generally left economic matters in the hands of private enterprise and of Ludwig Erhard, his capable economics minister. Although Adenauer had never before held a diplomatic post, he developed great stature as a statesman. He served as his own foreign minister from 1951 to 1955. A Franco-German rapprochement and a strong tie to the United States formed the basis of Adenauer's European and world policies. Although opponents scornfully dubbed him the "chancellor of the Allies," Adenauer's negotiations with Germany's former enemies resulted in a plan of West European unity and prosperity which rivaled Charlemagne's empire in scope. From the early 1950s on, Adenauer offered to contribute to the European Defense Community and in 1954 to raise a new German army within NATO. Under his guidance West Germany became an active member of the Council of Europe, the West European Union, and the European Economic Community (European Union).

By the early 1960s Adenauer was an octogenarian and had come to be called Der Alte (the Old Man). He was increasingly out of touch with the new generation, liberal opinion, and the thaw in East-West relations. He resigned the chancellorship under heavy political pressure from his own party in 1963. When he died in 1967, his funeral occasioned an almost unprecedented foreign tribute to a German chancellor.