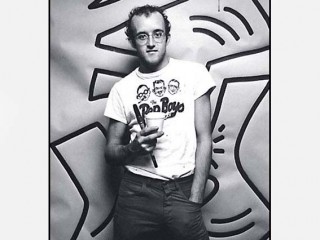

Keith Haring biography

Date of birth : 1958-05-04

Date of death : 1990-02-16

Birthplace : Reading, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-08-23

Credited as : Artist, social activist,

2 votes so far

Influences.

A lover of cartoons and science-fiction television shows, young Keith Haring responded to encouragement from his artistic father by creating his own vividly original stories and illustrations. He moved to New York in the late 1970s and studied abstract expressionist painting at the School of Visual Arts, where he befriended fellow artist Kenny Scharf. Frustrated with the insistence on artistic tradition at the school, Haring began to work on a different scale, often drawing on giant rolls of paper he spread on studio floors. By 1979 Haring had become captivated by subway graffiti. Its raw energy and sense of color and life pleased his growing pop sensibilities, and its visibility in a public space appealed to his desire to reach everyone with his art. Using chalk instead of the typical graffiti artist's spray paint, Haring began leaving drawings on the rectangles of black paper that covered unused subway advertising space.

Village Days.

In 1979 Haring, Scharf, and artist friends such as Ann Magnuson began to organize group shows at Club 57, their new East Village hangout. Their "art parties" were a mixture of performance pieces, comic skits, videos, and visual art, including Haring's graffiti images. Having touched off a vogue for "club art," Scharf and Haring became the leading proponents of "fun art," a form that borrowed freely from the images of popular culture (especially cartoons). Haring arranged an "exhibit" of graffiti art at the Mudd Club in the East Village that turned into a free-for-all; he and hundreds of others covered the club and the surrounding area with colorful tags. In 1981 he began working for gallery owner Tony Shafrazi, who started showing the young artist's work. The following year Haring attracted the attention of critic and the press with a show at the Rotterdam Arts Council and with his contributions to a group exhibition at the trend-setting P.S. 1 Gallery on Long Island. In 1983 he participated in the Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial. Arrested for "criminal mischief" while decorating a subway space in June 1982; the undaunted Haring continued the practice long after his gallery work began to sell--and sell it did!

Exposure.

Haring's distinctive images, which often resembled thickly outlined hieroglyphics or cave drawings, became perhaps the most pervasive, influential, and popular art of the 1980s. While his gallery works sold to collectors for as much as $350,000, the images themselves seemed to belong to the world. While some of his paintings were being displayed at museums, Haring also created murals for schoolyards or on the sides of inner-city buildings. In 1982 one of his drawings was displayed for an entire month on the Spectacolor billboard over Times Square. In 1985 he created a giant canvas of Aztec-inspired figures for the dance floor at the New York club The Palladium and a giant painting to be auctioned off at the Live Aid concert in Philadelphia. He painted clothing for Madonna and Grace Jones, sets for a 1985 MTV concert, sets and props in 1984 for dance works by Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, and a curtain for a Roland Petit ballet presented in 1985. That year, in what became an international event, he spent three days creating an epic mural illustrating the Ten Commandments for a French museum. In 1986 three Haring works were placed in the sculpture garden at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

Images.

Though the media helped to popularize Haring's "radiant" children, winged television sets, and alligator-headed dogs, Haring was his own best publicist. To reach the largest audience possible, he began marketing a line of products featuring his most popular images, and in 1986 he opened his own store, The Pop Shop, to sell his wristwatches, magnets, coffee cups, tote bags, coloring books, and T-shirts. Haring was as committed to charities and social causes as he was to his brilliant self-marketing, and his seemingly naive, childlike images often had a political subtext. Radiant Child carried a warning about the perils of the nuclear age, while Haring's television sets spoke of a technological society out of control. Other seemingly innocuous drawings included messages about social violence or indifference, racism, and approaching apocalypse. "I have strong feelings about the world," he said. "I want my art to make people think." In 1986, as a "humanistic gesture," he painted a giant mural on the Berlin Wall in the colors of the East German and West German flags. He called it "a political and subversive act--an attempt to psychologically destroy the wall by painting it." Haring also enjoyed creating art for children, including a set of permanent murals for the children's division of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York in 1986.

Last Years.

Several of Haring's most political works dealt with the indifference of the U.S. government to the AIDS crisis. After learning that he himself had the AIDS virus, Haring took the same energetic, life-affirming attitude toward his illness that he had toward his art. He was open about his condition and met with groups of children to help educate them about AIDS. "The hardest thing is just knowing that there's so much more stuff to do," he said. "I'm so scared that one day I'll wake up and I won't be able to do it." Haring continued to work until just a few weeks before his death on 16 February 1990, painting murals, making giant sculptures for public spaces and playgrounds, and teaching art to disadvantaged youths. Major shows of his work have been held in Vienna, London, Los Angeles, and Helsinki, at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and at the Spectrum Gallery in New York City. In 1988 the Museum of Modern Art featured works by Haring in an exhibit titled Committed to Print, and in June of that year Haring contributed two giant banners to a seventieth birthday tribute to Nelson Mandela at Wembley Stadium in London; seventy-two thousand people attended the event, and an estimated five hundred million worldwide watched it on television--helping to fulfill Haring's desire to reach the largest possible audience. "You can't just stay in your studio and paint," he said. "That's not the most effective way to communicate."